“As an extraordinary testimony to the tradition of European baths, sophisticated Baden- Baden, is a city of health care, leisure and social interaction, where architectural prototypes and an urban planning typology emerged that is unparalleled by anything that has existed before.“

Lisa Poetschki (Städtische Koordinatorin

UNESCO World Heritage, Baden-Baden)

After an eight-year preparation period, Baden-Baden, in collaboration with ten other renowned European spas, officially applied for UNESCO World Heritage distinction under the title “Great Spas of Europe” in January 2019.

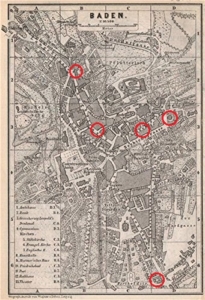

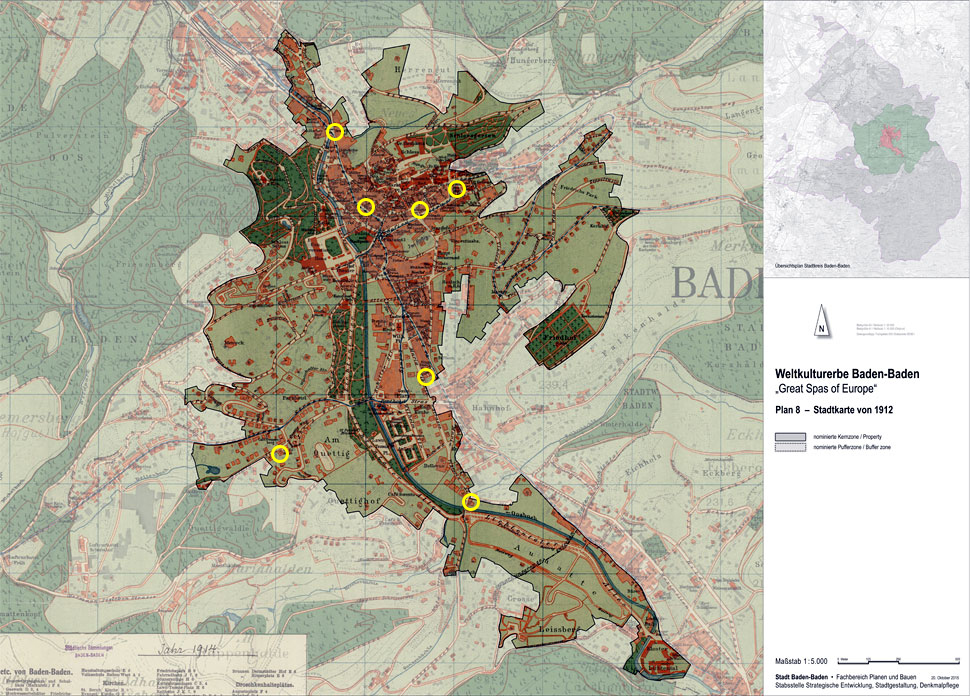

For this reason, The European Heritage Project decided to support this ambitious endeavour of the city of Baden-Baden and has acquired seven, partly severely neglected, historically meaningful heritage buildings with precious building substance worthy of preservation. All buildings are located in the heritage area between Lichtentaler Allee and Friedrichsbad in the “world’s smallest metropolis”.

The ensemble acquired by The European Heritage Project consists of mid-19th to early 20th century buildings from the Belle Époque. The ensemble includes a residential building designed by Johann Ludwig Weinbrenner, extravagant villas, opulent townhouses, the so-called “Alte Polizeidirektion”, and even the building which once housed one of the most prestigious luxury hotels in the city, the Deutscher Hof. Together with the two traditional spa hotels Europäischer Hof and Badischer Hof, which still exist today, the old hotel building formed the picturesque Belle Alliance Square where the Capuchin monastery, built in 1631, previously stood

MORE | LESS

Discovered by the Romans two thousand years ago and valued for its natural thermal springs, even by the Roman Emperor Caracalla himself, Baden-Baden experienced its heyday as the “summer capital of Europe” in the 19th century after the establishment of its casino. The spa town pioneered the development of modern tourism and established itself as Europe’s unofficial political and social stage, competing for supremacy with other major metropolises of the time as a cultural centre and popular retreat.

The spirit of famous guests of Baden-Baden such as Clara Schumann, Fyodor Dostoevsky, William Turner, Otto von Bismarck, and Queen Victoria, is still noticeable today. It is precisely this historical and cultural wealth that The European Heritage Project aims to preserve and protect and to contribute to the preservation of this remarkable spirit as a serene and cosmopolitan retreat that has inspired society and the great minds of Europe ever since.

THE HISTORY OF BADEN-BADEN

Baden-Baden is a spa town and is also known as a media, art and international festival city. The Romans already appreciated the hot thermal springs at the edge of the Black Forest for relaxation and recreation. In the Middle Ages, Baden-Baden was the residence of the margraviate of Baden, which in turn gave its name to the state of Baden. After a catastrophic fire in 1689, the town lost its status as the official town of residence to the neighbouring Rastatt, but remained the district seat for the state of Baden. The spa town was rediscovered in the 19th century and developed into an internationally important meeting place for aristocrats and wealthy citizens, also thanks to the income from the casino. A rich, well-preserved material and immaterial heritage has been preserved from this heyday in the 19th century.

The first traces of settlement in the valley of the Oos River can be found from the Mesolithic around 8000 to 4000 BC. However, it was not until the Romans discovered and learned to appreciate the local thermal springs, which were up to 68 degrees Celsius hot, that Baden-Baden gained in importance. After the occupation of the areas on the right bank of the Rhine by Emperor Vespasian between the years 9 and 79 AD, the Romans founded a military camp on the Rettig plateau south of today’s old town around the middle of the 70s AD. After the settlement and the bathing facilities in the area of the old town were completed, the camp gave way to an administrative district. The colony Aquae developed into a military spa and in the second century became the administrative seat of the Civitas Aquensis.

In around 260 AD, the Germanic tribe of the Alamanni conquered the area. The area came under Franconian rule around the year 500 and became the border town to the Alemannic tribal area that began south of the Oos River.

The first documented mention of Baden-Baden is controversial. According to medieval sources, the Merovingian king Dagobert III (699-716) donated the march and its hot springs to the Benedictine monastery of Weissenburg in today’s Alsace in 712. In the earliest documents, the place was referred to as “balneas in pago Auciacensi sitas” (baths located in the Oosgau region), and in other places as “balneis, quas dicunt Aquas calidas” (baths they call hot springs). A document from the year 856 also refers to the same donation but is controversial. The first verified document for today’s Baden-Baden is a deed of donation from the year 987, in which the Roman-German king Otto III (980-1002) who later became emperor, called the village “Badon” and mentioned a church for the first time. In the year 1046, there are references to the town being granted market rights.

Hermann II of Baden, of the House of Zähringen, (1060-1130) acquired the area around Baden-Baden at the beginning of the 12th century. He built Castle Hohenbaden in around 1100 and was the first to use the title Margrave of Baden in 1112. In 1245, the Cistercian monastery Lichtenthal was founded and Baden acquired its town charter at that time. Baden was first explicitly mentioned as such in 1288. With the permission of Margrave Friedrich II of Baden († 1333), the thermal springs were used for baths from 1306 onwards for the first time since ancient times. At the end of the 14th century, a castle was built on the Schlossberg, forming the core of today’s Neues Schloss (New Castle) on the Florentinerberg. The first spa taxes were levied in 1507, and a spa director was appointed who from then on took care of the aspiring spa business. From 1500, the town was part of the Swabian Imperial District, one of the ten government areas under the Holy Roman Empire. After the division of the margraviate of Baden in 1535, today’s Baden-Baden remained the residence of the Bernhardine line and the capital of the margraviate of Baden-Baden. After the end of the strongholds, the margraves moved from Castle Hohenbaden to the so-called “New Castle”, a splendid Renaissance complex with large parks and terraced gardens that overlooked the entire city. The old town of Baden was built around this castle, the medieval buildings of which still characterise the narrow maze of alleys of the Schlossberg.

During the Nine Years’ War(1688-1697), (also called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg), Baden-Baden was burned down by French troops on 24 August 1689. As a result, the operation of the baths came to a standstill. In 1705 Louis William, Margrave of Baden-Baden (1655-1707) moved his residence to Rastatt, but Baden-Baden, nevertheless, remained the official city of the margraviate.

Cut off from court life, Baden-Baden fell into a deep slumber. It was not until the time after the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815) that the city experienced a completely unexpected upturn. Louis Philippe I (1773 –1850), who became French king during the Restoration after the abdication of Napoleon, driven by pious zeal, passed a law in France which was to have far-reaching consequences for Baden-Baden in particular. He banned all gambling as well as the entire casino system in France. At that time, the French entrepreneur Jaques Bénazet (1778 – 1848) was the leaseholder of the large casinos in and around Paris, including the Palais Royal, which he was no longer allowed to operate. Bénazet, who in the meantime had achieved considerable prosperity and was familiar with the global upper class consisting of the nobility and the wealthy bourgeoisie, was searching for a new location for his gambling business, but on an even larger scale. Baden caught his eye because there he found favourable conditions for his project.

Baden, which in the meantime had become The Grand Duchy of Baden, had been a reliable ally to the French during the Coalition Wars. To that extent, France had a certain historical sympathy for the region and the citizens of Baden were inherently Francophile. Furthermore, the ruling house of Baden, although it was now a Grand Duchy, was not a despotic regime, as may have been the case in Prussia. Nor did it have a powerful king, as did Bavaria, who ultimately wanted the last word. The ducal house of Baden was simple and, fortunately, not too powerful. To crown it all, Baden was also a tourist attraction with the hottest springs in the empire. And what was ultimately particularly attractive for Bénazet’s plans: the medieval-looking city offered huge areas for development outside the old city walls along the river Oos.

Bénazet wanted to realise his master plan in Baden. He did not merely want to build one or two casino complexes; he wanted to execute a total “terraforming” immediately. His concept envisaged the expansion of the theatre with numerous boxes in the style of the Paris Opera. He intended to integrate a conversation centre, a spa house, several casinos, concert buildings, and numerous Kneipp hydrotherapy and spa facilities into a park. Furthermore, he planned several large palace-like hotels such as the ones already found in Paris but not yet in Germany. In addition to the existing Catholic churches, provision would be made for places of worship for other religious communities, such as a Russian Orthodox, a Romanian Orthodox, an Anglican, and a Protestant church, in order to reach all European upper classes. And finally, according to the motto “Think Big”, he planned to build a promenade extending from the planned train station to the distant Lichtental monastery almost three kilometres(!) away.

To realise his elaborate plans, Bénazet did not require millions (in today’s currency), he needed billions. And thus he sought and found investors to co-finance the ambitious project. It was to pay off for everyone! Everything that Jaques Bénazet, and later his son Edouard, had planned was realised, and even today visitors can admire the kilometre-long and unique Lichtentaler Allee.

His plans worked and all of Europe came to Baden-Baden. Queen Victoria was a welcome guest, as was Napoleon III and the entire Russian nobility. Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms also lived here. Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote his novel “The Gambler” in Baden-Baden, and German Emperor William I was a summer guest for 40 years in a row, and even today, a plaque commemorates the unsuccessful assassination attempt in 1861 in Lichtentaler Allee not far from the Kettenbrücke. 19th century Baden-Baden was like Monte Carlo in the 1950s and 1960s: probably the most famous place in the world for the high society of the time.

Many stately guests transformed Baden-Baden into the summer capital of Europe. Artists, poets, intellectuals, politicians, and aristocrats flocked to Baden-Baden in summer, while Paris was the official winter capital. Baden-Baden was particularly popular in its heyday among German composers and musicians such as Clara Schumann (1819-1896), Richard Wagner (1813-1883) and Johannes Brahms (1833-1897, as well as Russian and French intellectuals such as Victor Hugo (1802-1885), Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821-1881) and Lev Tolstoy (1828-1910). From 1858 international horse races took place on the specially designed Iffezheim racecourse. In 1872 the International Club of Baden-Baden took over the organisation of the horse races.

Baden-Baden owes its present sophisticated style to urban planners and architects such as Friedrich Weinbrenner (1766-1826).

THE OVERALL SITUATION TODAY

Thanks to its history and, especially its cultural proximity to France, Baden-Baden was spared during the Second World War and is therefore one of the best-preserved health resorts in Germany. The townscape is characterised by outstanding examples of spa architecture from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Nevertheless, numerous architectural blunders erected during the 1970s and 1980s as part of a large-scale modernisation project changed the cityscape. In addition, from the 1960s onwards, numerous unfortunate and unnecessary demolitions took place which resulted in the permanent destruction of many historic buildings that were worthy of preservation.

Today, the Kurhaus (spa house) with its famous casino is the architectural and social centre as well as the landmark of the city. The old town of Baden-Baden boasts numerous shops and cafés that invite one to stroll around. In the spa district, the 19th century Neo-renaissance Friedrichsbad, and the Roman bath ruins, the remains of ancient thermal baths located below the market square and at the Friedrichsbad, are particularly worth mentioning. Further sights include the Kurhaus designed by Friedrich Weinbrenner, the artistic cascading Paradies waterworks, the Lichtenthal Abbey, a Cistercian nunnery, the ruins of the ancient Hohenbaden Castle (today known as the old castle, or Altes Schloß), as well as the Neues Schloss or New Castle, the former residence of the Margraves of Baden. Equally worth mentioning are the Trinkhalle, or drinking hall, by Weinbrenner’s successor Heinrich Hübsch (1795-1863), and the Lichtentaler Allee, a historic park and arboretum set out as a 2.3 kilometer avenue along the River Oos and which is still the heart and green lung of the city.

For the past few decades, the city has endeavoured to re-establish itself as a cultural centre, in some cases with great success. The younger generation is once again showing interest in the spa town. Travel and cultural sections of world-renowned magazines such as the New York Times and Monocle have returned Baden-Baden to the limelight.

The city therefore decided to have the historically unique urban ensemble protected as a World Heritage Site. In 2021, it was finally inscribed on the list of World Heritage Cities under the heading “Great Spa Towns of Europe”.

PROJECT GOAL

“Here in Baden I have beautiful nature as well as artistic interaction because everything comes here.” With these words Clara Schumann (1819 – 1896), a famous German musician and composer and the wife of the composer Robert Schumann (1810 – 1856), summarised her motives for moving to Baden-Baden.

The European Heritage Project has acquired seven neglected to ruinous listed buildings within the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Baden-Baden. The aim of this commitment is not only to improve the condition of the respective buildings and return them to their original state, but also to support the city in making the historic spa town a popular place to live and a desired travel destination. In addition, the cityscape should increasingly live up to its claim as a preserved cosmopolitan city of the Belle Époque, given that numerous buildings from the heyday of the spa town were randomly demolished from the middle of the 20th century onwards.

Although the town’ s landmarks such as the drinking hall, the Lichtentaler Allee, and the casino play a significant role in defining the town, they are not the only buildings that give Baden-Baden its unmistakable appearance. Visitors from abroad, investors and architects, but also those born in Baden-Baden, have helped shape the cityscape in countless subtle ways between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. They left their mark in the form of stately villas and townhouses, thus creating the architectural diversity that has become a characteristic feature of Baden-Baden.

Preserving this cultural and architectural heritage is a project that a city can hardly manage on its own. Therefore, The European Heritage Project decided, within the framework of its statutes, to actively support the city in this endeavor.

In 2021, UNESCO awarded the city of Baden-Baden the title of World Heritage Site. The EHP also played a significant role in this as the former Lord Mayor Margret Mergen announced.

The individual projects:

GRAND DUCAL ADMINISTRATIVE BUILDING

Sophienstrasse 47, built in 1842

INFORMATION

The “Alte Polizeidirektion” (old police headquarters), as the palatial building on Sophienplatz is popularly known, is probably the most famous secular building in the spa town, along with the castle and spa facilities. Erected as a grand ducal administrative building in 1842, it radiated the new extravagant self-confidence of the state of Baden. Located at the end of the famous Sophienallee, it connects Baden’s old town with the spa quarter.

Situation at time of acquisition:

Once threatened with demolition, and after years of vacancy, the building complex, anchored in the city’s memory as the “old police headquarters”, was restored and modernised in cooperation with the heritage office. The former owner had lost interest in the building and was looking for other investment opportunities. Given this situation, The European Heritage Project was asked to include this townscape-defining property in the Baden-Baden ensemble project in order to preserve it for posterity. In July 2019, The European Heritage Project acquired the building.History:

The building complex was originally built as a grand ducal administrative office in the style of a Renaissance Tuscan villa. Friedrich Theodor Fischer, a Weinbrenner scholar and at the time the head of the Oberbauinspektion (Higher Building Inspection) in Karlsruhe, was commissioned with the planning of the building. After the completion of the construction project, the grand ducal district court, several official residences, and the police station were accommodated in the building from which the Grand Duchy of Baden was administered. From 1942 the prestigious building served only to house the police headquarters until they moved to Weststadt in 1975.

For decades, however, the intrinsic value of the building had not been adequately appreciated in the future planning of the spa and baths administration. In 1964, a decision was made to demolish the old police headquarters and the imposing arched building was to give way to a planned green belt. At the time, Weinbrenner’s buildings were considered worthy of preservation, but not those of his students and successors. Until 1977 the demolition was still being considered. The impressive building, which had a decisive impact on the cityscape, almost met with the same fate as many 19th-century historic buildings which were sacrificed from the 1960s to the 1980s, primarily in favour of new buildings and car parks. Fortunately, however, in 1978 a group of monument preservationists campaigned vigorously for the conservation of the historic building and founded the “Schutzgemeinschaft alte Polizeidirektion” (Protection Association for the Old Police Headquarters), which rapidly attracted an unusually high level of attention and popularity in scientific circles.

In 1982, the Museum for Mechanical Musical Instruments moved into the building. Subsequently, the building stood empty for years but today it is open to the public again and a modern medical centre is housed within the old renovated walls.Architecture:

In 1839 Friedrich Theodor Fischer was commissioned to erect a building at a central location which, on the one hand, would meet the functional requirements of a stately administrative complex with a courthouse and, on the other hand, meet the representative demands of the authorities and the expectations of the clientele of an up-and-coming spa. The result was a three-storey central building which, together with two symmetrically arranged wing buildings, enclosed a small garden square with a central fountain at the end of Sophienallee. The entire complex was constructed of high quality materials such as sandstone.

In terms of style, Fischer oriented himself to the Italian Neo-Renaissance style. The three-storey façade of the main building is strictly structured accordingly. On the ground floor, above a suggested bossage next to the high, representative entrance there are three high, rounded windows which are reminiscent of Palladio and which are also to be found on the other floors. The Grand Ducal coat of arms can be seen above the entrance. To the right and left of the entrance portal, on high columns, there are figurative representations of the allegories of justice and law, Justitia and Lex. Both of the higher storeys are divided by cantilevered cornices. Bronze tondi depicting griffin heads are located under the eaves and the roof consoles above the windows of the second floor. The two curved side wings, which branch off from the main building in a semicircle to the right and left, are a special feature. Two classicist pavilions, which once served as guardhouses, form the end of these wings. To emphasize this detail, the corners of the building are optically highlighted with heavy bossages and a central high entrance gate.Restoration:

In the course of the renovations carried out by the previous owner, the side wings including the pavilions were covered with an additional, simple, cube-shaped modern storey, which discreetly blend into the historical architecture.

The building is accessed via several staircases. First, there is a small staircase over the garden forecourt, which is directly connected to the main staircase. The building can only be accessed after walking through an inner colonnade. The original entrance doors are divided into eight glazed elements. The interior contains various neo-Gothic elements, such as the high, narrow cross vaults on the ceilings above the staircases and in the entrance hall, as well as stone balustrades with star-shaped ornamentation, some of which end in Tuscan columns. The generously designed, high, round arched doors in the rooms and the many illuminating windows emphasise the open design of the architecture. The simple, white walls and the polished, anthracite-coloured d granite stone of the floors and stairs make the entrance hall appear even more spacious.

The entire building has a distinct urban character reflecting the new self-confidence of the ruling dynasty of Baden after it was elevated to the status of Princely Grand Duke in the first half of the 19th century.Present use:

The building is now used as a medical centre, thus regaining its public accessibility, and visitors can enjoy the beautiful architecture from both the outside and the inside. As a lively hub between the spa quarter and Sophienstrasse, it significantly contributes to increasing the attractiveness of the city centre.

“WEINBRENNER” BUILDING

Maria-Viktoria-Strassee 17, built in 1865

INFORMATION

The four-storey building, completed around 1860 as an essential part of a new district directly behind the evangelical town church on Augusta Square, represents the generous charm of the Belle Époque.

Designed by Johann Ludwig Weinbrenner (1790-1858), it was one of the few buildings planned by him purely as an apartment building. An upper-class spatial design and a classicist interior provide insight into the realities of life in the middle of the 19th century.

Situation at time of acquisition:

Before The European Heritage Project acquired the property in 2019, it was taken over by a private entrepreneur in 2003, who wanted to redesign and completely modernise the building and change its function. Duplex garage parking spaces were to be created in the courtyard, and an external elevator built. Due to the resistance of the monument conservation authorities and the resulting time delays, the owner lost interest in the property and left it as a partially gutted shell.From the outset, the architectural and socio-historic relevance of the building was clear to the curators of The European Heritage Project. As one of the first buildings in Baden-Baden designed by Johann Ludwig Weinbrenner (1790-1858) as a purely rental building, it represented an important historical and architectural testimony and marked a turning point in architectural history. Due to the acute risk of the entire building being significantly changed, The European Heritage Project decided at the beginning of 2019 to include the largely vacant building in its portfolio in order to preserve it for posterity.

History:

Maria-Viktoria-Strasse is part of a new district designed by Friedrich Eisenlohr (1805-1854) between 1855 and 1865, which included Ludwig-Marum-Strasse, Ludwig-Wilhelm-Strasse, and Schiller-Strasse. The plans of the building were drawn up by Johann Ludwig Weinbrenner (1790-1858), the nephew of the architect Friedrich Weinbrenner. From 1802 to 1808 Johann Ludwig Weinbrenner studied architecture at his uncle’s construction school in Karlsruhe. Until 1814 he worked in the grand ducal building office and supervised the construction of the new evangelical church in Karlsruhe. From 1814 to 1817 he studied on a scholarship in Rome, which resulted in a friendship with Friedrich von Gärtner. From 1819 he was a district master builder in Müllheim, after which he occupied the same position in Lörrach. From 1825 he was a district master builder in Baden-Baden, and from 1835 in Rastatt. In his later buildings, he increasingly broke away from the classicist architectural style of Friedrich Weinbrenner and joined the historicising direction of the round-arched style, as represented by his successors Heinrich Hübsch and Friedrich von Gärtner. The building located at Maria-Viktoria-Strasse 17 was created during this period.Architecture:

The prestigious residential building was built between 1855 and 1860. The building is also cartographically listed for the first time on a town map from 1889. The building is of particular value as a source for the history of Baden-Baden, especially for art and architecture, but also for social history. The building reflects the typical spatial and aesthetic characteristics of upper-class residential construction of its time. The three-storey building features representative forms of late classicism, which enjoyed great popularity throughout Europe in the second half of the 19th century, especially in spa towns. The building with its shutters and hipped roof, flamboyantly structured by storeys and window sills, has three splendid, artistically arranged balconies with richly decorated iron gratings. The window parapets are also ornamentally decorated. In the interior, the spacious impression is further enhanced by a wide staircase wide side stairs and elegant classicist cast iron decorations. In addition, the stairwell is adorned with stained glass windows with geometric shapes and floral patterns, creating a colourful display of light.Both the building and its urban setting illustrate developments in the history of the region. It is a rare architectural-historic testimony of high documentary and conservation value with a well-preserved building structure.

Restoration:

The building was completely refurbished and modernised under the supervision of The European Heritage Project. The modern changes made by the previous owner were carefully dismantled. In addition to the overall renovation, the original intention for the building to be used purely as a rental building, was particularly important. The construction work included the façade, the roof, and the entire interior including new attic apartments.In the entrance area, the modern artificial stone tiles were completely removed and subsequently replaced by historical cement tiles with a floral pattern. Concrete steps that were added at a later date were replaced by sandstone steps. In the stairwell, the wrought iron railing was repaired and the antique wooden handrail exposed. Red, natural fibre carpets were laid on all steps. A special aspect was the restoration of the missing coffered dado, which again adorns the entire entrance area and lends it a historic charm. To replace the door from the 1960s, a front door, designed according to a historical model, was installed and decorated with original historical iron grills and decorative elements. Historical crystal chandeliers give the entrance area a typical classicist character.

Modern drywalling was removed from all six residential units and all electrical, heating and sanitary facilities completely rebuilt. The two existing top floor apartments were comprehensively overhauled. The parquet floors, mostly from the first half of the 20th century, were reworked and preserved as far as possible. The windows and double doors in the apartments have been reworked and preserved as far as possible from the original inventory. The windows were improved in terms of energy efficiency by installing extremely thin double glazing to maintain the historic wings. In addition, all apartment entrance doors were refurbished to comply with the highest safety standards. All residential units now have underfloor heating.

The façade was improved and restored according to the specifications of the monument protection office. Missing shutters were added and the parapets overhauled.

Present use:

As was the case when it was built, the building is used today as an elegant but bourgeois apartment building.

DEUTSCHE HOF

Lange Strasse 54, built in 1870

INFORMATION

Located on the former Belle Alliance Square (today: Hindenburgplatz), where the Kaiser Bridge and the Luisen Bridge span the river Oos, the Deutsche Hof and its counterpart, the Badischer Hof, formed the prestigious entrance to the Baden city centre.

Since the Second World War, however, it was a mere shadow of its former self, and was an annoyance in its run-down state. Now, after restoration, the Deutsche Hof is to restore the square to its historical splendour.

Situation at time of acquisition

Prior to the acquisition by The European Heritage Project, the building was privately owned by an elderly couple who had used it as an apartment building. At least 20 years had passed since the building was last renovated. Due to significant structural interventions in the 1960s, in particular the unsightly façade and entrance design which no longer harmonised with the original historical architecture, the quality of the tenants gradually deteriorated. This also applied to the shops, which were still designed in the style of the late 1960s and sold second-hand and junk goods. Hardly anything remained which was reminiscent of the former splendour of the prestigious Deutsche Hof, one of the most famous hotels in the city. The previous owners were evidently no longer able to cope with the ongoing maintenance. For them the substantial renovation of the building and the restoration based on the historical model were impossible. This was the situation when The European Heritage Project acquired the building in February 2019.History:

The Deutsche Hof is located on Hindenburgplatz at the entrance to Baden-Baden’s historic old town. All who enter the city pass the once proud building. The former Capuchin monastery, which dominated the cityscape of Baden-Baden from 1631 to 1807, stood in the immediate vicinity until it was replaced at the beginning of the 19th century by the new Badischer Hof hotel. At that time, the square was lavishly designed, including a beautiful fountain and the columned belvedere which was later removed. In the 1870s, the planned hotel Deutsche Hof was built over an existing building. In the Baedecker travel guides of the time, the Deutsche Hof was recommended as renowned accommodation.According to historic drawings, the former Deutsche Hof had three storeys with an attic, and a fully covered hipped roof with seven dormers. At the time of its construction, the building was adorned with late Classicist to neo-Baroque elements, such as cornices which divided the house into its storeys, as well as window openings which, with the exception of the ground floor, had shutters and a total of six symmetrically arranged French balconies, which were lavishly decorated with floral iron balustrades and were separated from the rest of the façade by decorative pilasters. Furthermore, the ground floor was covered with a simple tile decor. The buiding also had a smaller side entrance to the right and a central portico flanked by columns.

In 1912, major renovations were carried out, which fundamentally change the property. Two upper storeys and a gable element were added. The façade was largely preserved. During the last renovations in 1912, the hotel and cinema were closed and the building converted into a residential building. From the 1960s, the ground floor served as a retail area for shops. The historical elements, such as stucco work and cast iron columns with floral decorations, disappeared behind plasterboard walls.

Restoration:

A review revealed that the structural situation was more critical than expected. Leaks in the roof were found with damage to the beam supports. The historical windows had been replaced by plastic ones. The main problem, however, was the façade of the building facing the square, which no longer reflected the once splendid appearance of the Deutsche Hof. The historic portico had been demolished. All elements of the façade structure, such as balustrades, cornices and French balconies, had been removed, leaving the façade looking plain, uniform and unexciting. Large shop windows had been inserted into the ground floor, which were framed by a uniform layer of granite slabs from the 1960s. In the entrance area, all wall panelling had been removed and the historic cement tiles replaced with easy-to-clean bathroom tiles. The remaining balconies, including the rusty railings, were not usable because they were partially in danger of collapsing. The entire building displayed the dreariness of the purely functional architecture of the 1960s. Large parts were in a state of advanced neglect.At the end of 2020, The European Heritage Project commenced with the restoration of the façades, the interior traffic areas, the retail units, the apartments, as well as the urgent roof repairs. The aim of the façade restoration was to re-establish the overall appearance of the Deutsche Hof based on the historical model. The intended façade design will return the focus to the building as a whole, and will make the original delicacy of the façade, which is still recognisable in the building fabric, visible again. The existing shops will be reduced from three to two business units, and the display windows reduced in size. Old interior decorative elements are to be exposed again. The base of the façade is to be designed as a series of bossages made from local sandstone which will correspond to the window frames and cornices of the entire façade. On the front façade, all windows will be replaced by wooden windows made according to historical models with correspondingly elaborate profiles and Goethe glass. From the first to the third floors coffered roof lights will be installed, and on the fourth and fifth floors lattice windows divided into small sections. Wooden folding shutters, instead of roller shutters, will be installed to structure the façade and to recreate the original window proportions. Historic decorative elements which are missing will be supplemented. A golden medallion, created by means of plastering, will be installed in the dormer, and the lettering “Deutsche Hof” will again adorn the building as it did originally.

The entire entrance area will be redesigned. Historic cement tiles will replace the simple bathroom tiles, and sandstone stairs will replace the concrete stairs. The missing dado will be restored, and the historical stucco work restored or supplemented. Throughout the entire building vigorous restoration and renovation measures are taking place. The work on the roof structure has already been completed.

Future use:

The building is used as an apartment building with store units from the end of the work in 2021.

TREUSCH BUILDING

Lange Strasse 12, built in 1893

INFORMATION

A further valuable monument in the heart of Baden-Baden’s pedestrian zone has been added to the portfolio of The European Heritage Project. The Treusch building impresses with its imposing façade, made entirely of sandstone with elaborately designed cast-iron balconies. Built in the neo-renaissance style, the listed building embodies the sophisticated architectural demands of the Baden-Baden society during the Gründerzeit, the great economic upswing in the mid-19th century, and is therefore an important witness of these times. In the pedestrian zone, it stands out from the row of commercial buildings as a unique gem.

Structural condition at time of acquisition:

Unlike the other buildings which were bought in a partially dilapidated condition, the Treusch building was in relatively good condition at the time of the acquisition in 2013. However, the intentions of the previous owners to fundamentally “modernise” the building were threatening. To protect this monument, The European Heritage Project decided to preserve the property for posterity and to include it in the Baden-Baden city ensemble project.History:

The building was built in 1893 by L. Treusch in a rich neo-Renaissance style, and in 1902 and 1903 it was extended on Küferstrasse by the architects Treusch & Schober. It is characterised by the fact that it is 9.5 metres higher than the adjacent “Haus Rössler”.The ground floor of the four-storey corner building has always been rented out as business premises. The first Tchibo branch in Baden-Baden was opened here in 1961. There are apartments on the upper floors.

Architecture:

Structurally, the property is characterised by its elaborately designed sandstone façade. The façade structuring elements on the upper floors are particularly opulent but on the ground floor consist of a rather simple panel décor. The structural elements are designed in an interplay of diverse ornamental shapes, such as triangular or segmented tympanums at the window openings, dentils below the roof, cartouches, scrollwork and interlaced ornamentation, and shell decor on the bay window, all of which lend a unique character to each of the upper floors.In addition to the many decorative elements on the sandstone façade, the impressive roof design of the corner tower is also striking. The tower is topped by a playful-looking onion dome with filigree decorative elements. The rest of the roof is simpler and has four gable dormers on both the left and right sides of the tower. Other stylistic features are the six balconies facing Lange Strasse, of which the cast-iron railings are decorated with floral motifs and lend a French flair to the building.

The large portal leading to the apartments via the side street is made of solid oak, but its playful iron grilles and window elements lend it a certain lightness. The entrance hall is characterised by Art Nouveau decor created during the second renovation in 1903. Original coloured cement tiles cover the floor, and the walls are decorated with white ornamental tiles. In the stairwell, a cast-iron spiral staircase leads to the upper floors, passing the large and lavishly designed tripartite stained glass windows. The glass triptychs originate from Hermann Westermann’s historic glassworks.

The apartments are accessed via solid wood ceiling-high portals with hinged doors. The living areas feature unobtrusive, white-painted wooden cassettes, wooden wall panelling and radiator panels as well as plain ceiling stucco. The original oak floors in the individual rooms are made of herringbone parquet and solid wooden floorboards in the corridors.

Renovation:

Despite the good general condition, restoration and maintenance measures had to be carried out on the balconies. Modern carpets were replaced by oak wood herringbone based on the original.Future use:

The property will be used as a residential and commercial building as it has been since the beginning.

CITY VILLA

Quettigstrasse 5, built in 1899

INFORMATION

In the historic villa area of Beutig-Quettig, which stands under monument protection, this stately city villa is a typical example of the prestigious upper-class architecture of the late Belle Époque.

Purchase Situation:

After the closure of a guest house that had existed for several decades, the villa in Quettigstrasse was occupied by an elderly couple until 2009. When the husband passed away, the widow decided to sell the building and moved out quite quickly. As a result, the house stood empty for more than four years until The European Heritage Project became aware of the property and finally acquired it in November 2014.History:

The building was designed by the architects Treusch & Schober in 1899 as a townhouse for the family of the district administrator Winzer. After the completion of their new home the family, however, lived here only until 1906 after which followed a frequent change of ownership. As early as 1914, the intended purpose of the building changed. It was converted into a guesthouse which was operated by its owner Hans Bilz until 1973 as the “Fremdenheim Haus Bilz”. However, most of the tenants lived there permanently after the war. In 1974 the villa was taken over as a residence by a married couple.Architecture:

The one and a half storey, plastered, late Belle Époque villa is built of light sandstone. The façade is particularly playful due to an avant-corps protruding from the building.As a structural feature of the façade, this element reflects a typical design element of the Renaissance and Baroque architectural style. Also striking are the gable construction decorated with pinnacles, the stately mansard roof, and the balconies with wrought-iron railings, including a covered veranda that appears to float. The wrought-iron elements of the house are reminiscent of the cast-iron architecture of 19th-century England and Scotland during the so-called Gothic Revival which combined ultra-modern materials with filigree and complex-symmetrical forms used in the High Gothic period. This construction method is often found in the park architecture of Victorian England.

In the interior, the architecture of the villa impresses with a generously designed staircase. The impressive room design is characterised by sloping walls and angles, thereby creating a certain intimacy, but also creating an openness and lightness due to the high ceilings and numerous windows.

The preservation of the listed building is in the public interest for both art historic as well as local historic reasons, as it represents an important example in the development of villa construction in the spa town of Baden-Baden.

Restoration:

The reconstruction work on the villa was completed in 2020. Essentially, the following measures was carried out:The façade was re-plastered and repainted according to the specifications of the monument protection authorities. The sandstone was generally in good condition and was partly stabilised, cracks were filled, and soot was removed by sandblasting. Wrought iron elements such as balustrades and balconies were stripped of paint and rust and re-sealed. A modern roof terrace was dismantled and the roof garden, with a wrought iron roof crest, was subsequently reconstructed according to the original building plans. The missing gable element was reconstructed. The flagpole on the side tower was replaced. Rusty sheet metal rain gutters were replaced by historically accurate copper gutters. Paint was removed from the preserved box windows, and the plastic windows were removed and replaced by reconstructions based on historic models with the conforming profiles and Goethe glass. The original window shutter systems were overhauled and restored to working order. All water pipes as well as the electrical and telephone lines were completely reinstalled.

In the interior, the floors, the wooden staircase leading to the individual floors, as well as the partially existing wood panelling were reworked. The majority of these elements had been preserved and only a few severely damaged and irreparable segments were partially reconstructed. The filigree ceiling stucco was augmented and partially reconstructed. The modern tiles in the interior were removed and replaced with cement tiles that were in accordance with architectural history. The sanitary facilities were dismantled and replaced by modern, timeless bathrooms based on historic models. A special detail is the elaborate fabric paneling on the walls, which give each room a very personal character and create a certain cosiness.

In the outside area, among other things, the staircase and patio were renovated. The exposed aggregate concrete slabs which had been laid in the 1970s were removed and replaced by historic sandstone slabs. A new, cast iron banister was installed, the design of which is based on the other cast elements. The entrance gate and bell system were modernised.

In a final step, the remaining gardens were restored

Full completion took place in 2022.

Future use:

The villa is be used as a single-family residence in line with its original concept.

SONNENHOF

Sonnenplatz 1, built in 1901

INFORMATION

Originally planned and operated as a hotel, the Sonnenhof was the stage for numerous tragedies. Located in the middle of the old town on Sonnenplatz, the prominent building experienced various fates. From shattered dreams to the arbitrariness of the National Socialists, the Sonnenhof had many stories to tell until it fell victim to a devastating fire in 2019.

Purchase Situation:

After prolonged vacancy, with the exception of a grocery store on the ground floor, the building on Sonnenplatz was in an extremely neglected condition as no maintenance measures had been carried out since its construction. When the building was finally put up for sale in 2004 due to financial difficulties, The European Heritage Project won the bid with its restoration concept.History:

The residential and commercial building Sonnenhof was built in 1900 according to plans by the architects and property developers Adolf and Heinrich Vetter. Originally there were two small buildings at this location which were used as residential buildings with shops on the ground floor. The small houses stood within the city walls which existed until the beginning of the 19th century, and opposite the spa inn “Zur Sonne”, founded in the 15th century and eponymous for the subsequent Sonnenplatz. Until 1850, four old houses on this site testified to the cramped conditions within the city walls. When these buildings were demolished, a generous connection was created between the centuries-old Gernsbacher Strasse and the newly built Sophienstrasse, and Sonnenplatz came into beingThe new address Sonnenplatz 1 was specially created. The planned hotel, which was to be named “Sonnenhof”, opened in 1901. 20 guest rooms with 30 beds and a well-equipped restaurant for 100 guests were to become a special attraction in this part of the city. However, these goals were not achieved and operations ceased in 1907. The property was used as an apartment building until spring 1919.

In 1919, Theodor David Köhler (1880-1942) and his wife Auguste Mittel Stern (1876-1942) took over the property and opened the Tannhäuser hotel. After a short time, the couple had built up a large circle of satisfied, mainly Jewish, patrons. Yet, when the National Socialists came to power, there were anti-Semitic riots in Baden-Baden. The hoteliers were ordered in 1938 to rename the hotel Köhler Stern. The November Pogroms (9 – 10 November 1938), which ended with the fire in the nearby Jewish synagogue, put additional strain on the hotel operations. Finally, in 1939, Theodor Köhler was forced to sell the historic property to the fishmonger Rudolf Höfele for 68,000 Reichsmark on 14 February, whereby a so-called Jewish tax of 65,800 Reichsmark was levied which Köhler had to pay to the city of Baden-Baden immediately. In 1940, the Köhlers were deported to the former French internment camp Gurs. In 1942, they died in the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Today, two so-called Stolpersteine or stumbling blocks, brass memorial plaques at Sonnenplatz 1, commemorate Theodor and Auguste Köhler. Höfele operated his renowned specialist shop for fish, game and poultry until 1987.

In June 2019 the building suffered a new stroke of fate. Due to an electrical short circuit in the attic, a fire broke out which turned into a blaze. The building was severely damaged by the fire to the extent that only the exterior walls were left standing and considerable historic substance was lost.

Architecture:

The three-storey building with its ornamental sandstone façade is designed in elaborate neo-Gothic forms. It is characterised by a spectacular corner tower which has bay windows and is crowned by an onion dome with a spire. The roof has six additional dormers, also covered with onion domes. Further neo-Gothic elements include the round and pointed arches which serve as window and door openings, as well as the façade structuring elements, such as pilaster strips, struts and tracery. The staircase is dominated by a consistent Art Nouveau décor, from the ceiling and wall stucco, the filigree banisters and ornate centime tiles, to the door frames and arabesques which serve as decorative door arches.The symbol of the sun played an important part in both the architectural interior and exterior design, and is repeatedly found on the façade. Above the entrance, a woman’s head carved out of sandstone with a sunflower as headdress greets residents and guests. A picturesque sundial in one of the two gables under the roof shows passers-by what the time is. The building, with its existing original staircase, is an important example of the development of the inner city of Baden-Baden.

Restoration:

At the time of the acquisition, it was clear that a complete general renovation of the building was necessary. The visible sandstone façade was friable and cracked due to moisture penetration and massive frost damage. The lower storeys and basement rooms also showed severe damage to the masonry, including considerable salt efflorescence. The roof, partly made of sheet metal and roof tiles, and the little copper towers were in a dilapidated condition. Furthermore, some ceilings were no longer stable due to broken beams.After the building had been initially safeguarded, and after clarification with the local building and monument protection authorities, the actual restoration began in 2015. For five months construction workers, restorers and craftsmen restored the historic building on Sonnenplatz to its former glory. The extensive renovation work was completed in the spring of 2016.

Only three years later, a tragedy occurred resulting in a severe setback for all parties. The building was severely damaged by a fire on 15 June 2019, to the extent that only the exterior walls were left. A cable fire is said to have been the cause. Once again, the entire building fabric was in danger of being lost.

The fire had broken out in the roof area and destroyed large parts of the building. The entire roof truss and top storey were completely burnt out. There was less fire damage to the lower floors where the main damage was however caused by the ingress of extinguishing water.

With great commitment, The European Heritage Project dedicated itself to the renewed full-scale restoration and reconstruction after the disaster. The extensive restoration work is expected to be completed in summer 2021.

After initial measures for static safeguarding and the subsequent drainage of the extinguishing water, the entire roof was gradually restored. Large parts had to be laboriously reconstructed, such as the two-ton spire. In the presence of the Mayoress of Baden-Baden and the Board of Trustees of The European Heritage Project, the spire was returned to its original position with the help of a crane.

In the interior, burned down walls were rebuilt, fire protection insulation installed, all electrical systems reinstalled, and the historically valuable stucco elements safeguarded and reconstructed.

Future use:

The building is once again used as a residential and commercial building. On the ground floor there is a café roastery with its own sales outlet.

VILLA KETTENBRÜCKE

Maria-Viktoria-Strasse 53, built in 1902

INFORMATION

Villa Kettenbrücke was probably one of the most luxurious villas that Baden-Baden could boast. The property, with more than 1,000 square meters of living space, located in the middle of the famous Lichtentaler Allee, with its own beach on the Oos river, displayed all the splendour of the Belle Époque.

Purchase Situation:

Villa Kettenbrücke underwent constant changes of ownership since the 1950s. Initially the building was bought at the end of the Second World War by a farmer from Münster who subsequently sold it to a Liechtenstein corporation in 1959. In the mid-1980s, the villa was sold to a local real estate company that intended to carry out extensive renovations. However, these plans never came to fruition. In the meantime, the building repeatedly served as a film set until it was finally taken over in 2011 by a Russian oligarch who had the building, which had been occupied until then, vacated. The new owner strove to have the listed building repaired and plans were made for a prestigious retirement home for him and his family. However, this project was not realised as the owner experienced financial difficulties, resulting in vacancy leading to neglect. Increasing cases of vandalism and the necessity to raise cash eventually motivated the owner to sell the property. Concerned about another disadvantageous change of ownership, residents contacted The European Heritage Project. The Russian owner was finally contacted via a conspiratorial intermediary and the property acquired in February 2019.History:

Villa Kettenbrücke was planned and designed in 1888 by the Vetter brothers for the Baden-Baden hotelier Paul Riotte and his wife Mathilde Silberrad. The plans integrated a smaller former building from the first half of the 19th century. The building was, however, not completed until 1902, since ownership had passed to the renowned veterinarian and natural scientist August Lydtin (1834-1917). After his death, the villa was converted into an apartment building, which was occupied mainly by people of high social standing, such as Dorothea von Frankenberg und Ludwigsdorf, the court assessor Hermann Grote, senior civil servant Max Timme, and Lieutenant General Theodor Stengel.During this time, the building on Lichtenthaler-Allee witnessed a dark period in German history. Emilie Barbara Greiner (1882-1940) had lived in the building since 1923. She was diagnosed with paranoia and throughout her life had lived in several sanatoriums and nursing homes until she was ”transferred” to the Grafeneck Euthanasia Centre near Gomadingen in the district of Reutlingen in Baden-Württemberg in 1940, where she was killed. Today, a so called Stolperstein or stumbling block, a brass cobblestone-shaped memorial plaque in the pavement in front of the entrance to Villa Kettenbrücke, commemorates the tragic fate of the euthanasia victim Emilie Barbara Greiner.

Architecture:

The property has an idyllic, quiet location, surrounded by trees, with a river-side east façade, directly on the famous Baden-Baden promenade, Lichtenthaler-Allee. The spacious two-storey, plastered, sandstone structure with corner tower and lantern is characterised by wrought iron balcony railings. To the north, the villa has a gable in late classicist style. The two-tiered design of the house is particularly striking, especially the two one-and-a-half storey high mansard hipped roofs with their numerous barrel dormers. The façade facing Maria-Viktoria-Strasse impresses with its simple straight lines, narrow house entrance, and carefully arranged windows and façades. A certain playfulness is revealed in the garden on the courtyard side, characterised by a cast-iron spiral staircase which seems to visually separate the two wings of the building. However, the true gems of the building are the spacious winter gardens on the ground floor, and the two upper floors of which the artistic windows are decorated with botanical-looking orchid tendrils.The interior of the building features numerous wooden floorboard and parquet floors still preserved in their original condition, double wing doors, elaborate wall and ceiling stucco, wooden cassettes and panelling, historic wall tiles and cement tiles, massive banisters and portals, magnificent stained glass windows, and many other decorative elements that have been preserved in their original state dating back to 1902. The largely complete interior is a unique stroke of luck.

Restoration:

At the time of the acquisition by The European Heritage Project in 2019, the building fabric was generally in a dilapidated condition. The building had stood empty since 2011. Several windows had been broken by vandals who had gained access. Inside, the ransacking had continued and there were even traces of open fires.Electric wiring and water pipes had not been renewed for more than eight decades, which not only made the building uninhabitable but also presented a hazard as the building was not earthed. The walls and statics were also in a rundown state.

The restoration began in 2021. The building will be equipped with entirely new utilities. Electricity and water supply, sanitary units, heating and ventilation will be completely reinstalled. Despite the generally dilapidated condition of the building, it is quite remarkable that most of the historical features are still in place which will allow for a complete restoration of the building in its original form. The use of replicas, however, will be kept to a minimum. The original historic floor plan will be retained as far as possible. Walls and fixtures which were subsequently installed will, however, be dismantled. An overall renovation will be carried out.

The work was completed in 2024.

Future use:

Ground floor and 2nd floor are rented out as residential and office space.

The Belle Etage on the 1st floor and the outdoor areas are used for cultural events and artistic presentations.

“SCHABABERLE HAUS”

Gernsbacher Straße 4, built in 1896

INFORMATION

Where Lange Straße meets Gernsbacher Straße, i.e. in a prominent location, you will come across another monument of the European Heritage Project that is of great value to the city’s history – the Schababerle-Haus at Gernsbacher Straße 4. The house impresses with its imposing sandstone façade built in neo-Renaissance style. Cast-iron, French-style balconies with real gold ornamentation also lend it a certain lightness.

The listed building is typical of Baden-Baden’s inner-city residential and commercial architecture. The artistic and local historical significance of these buildings is undisputed, as they helped to establish Baden-Baden’s reputation as a cultural capital.Purchase Situation:

At the time of acquisition in February 2021, the property appeared to be in relatively good condition at first glance. The façade, for example, had no major defects. However, the interior of the house looked threatening. Due to the desolate condition of the roof, it was already raining in through various leaks, structurally important beams were already rotting and the building fabric was in danger of suffering major damage. Family-owned for decades, the last generation was finally unable to raise the funds to carry out the necessary renovations. To protect the monument, the European Heritage Project therefore decided to acquire the property in order to preserve it for posterity and include it in the ensemble project.History:

The building was erected in 1896 according to plans by architect Anton Klein in a rich neo-Renaissance style with a large gabled structure for the grand ducal court confectioner Hermann Schababerle. The house was built for an incredible 100,000 gold marks, which was an immense sum for the time. The first floor of the three-storey building has always been used as a store or sales area. In the basement of the building there was a pastry shop, which was tailored to the requirements of the master confectioner Schababerle. As a highly respected court confectioner who was privileged to supply the princely court, he needed an adequate bakery for his elaborate creations. After Schababerle’s death, the Kayser family of confectioners finally acquired the building in 1928 and ran the famous Café Corso from 1950-1980. After the family had to close the business and only occupied the upper floors, a men’s outfitter initially opened in the sales rooms until Villeroy & Boch finally moved into the space for its flagship store in 1995. The other floors remained empty.Architecture:

The building is characterized by an elaborately designed sandstone façade. Only local sandstone was used, with the reddish stone typical of Baden-Baden being used on the upper floors. The historic store windows can still be found in the store unit on the first floor, while the entrance is adorned with column-like façade elements. These elaborately designed components are continued on the upper floors and feature opulent dentil-cut elements on the Belletage. An interplay of different ornamental forms has given each floor a unique, individual character. As a stylistic break from the solid sandstone, the florally decorated cast-iron balconies lend a playful French flair. Real gold ornaments create additional elegant visual details.Another special feature of the building is the structure of the gable. This can be seen as a stylistic element typical of Klein’s architectural language. There is another house built by Klein in the immediate vicinity, on Lange Straße, which has an almost identical gable design. The peak rises like a staircase up to the highest point of the roof. This structure is framed by flanking pointed turrets on the dormer windows.

Inside the house, more specifically in the stairwell, there are well-preserved ornamental cement tiles. The walls are also decorated with ornamental tiles. The ceiling of the entrance area is shaped like a vault and features massive arch-like stucco elements. The stone staircase to the floors leads past the typical Baden-Baden windows with their small star patterns.

The apartments are accessed via solid wooden doors in the Art Nouveau style. The individual living rooms feature simple stucco ceilings. The original flooring is herringbone parquet made of oak.Restoration:

As already mentioned, the repair of the roof is particularly urgent in order to prevent major damage to the building fabric.

In addition, the apartments on the upper three floors need to be renovated and brought up to today’s standards. Here, the sanitary facilities in particular need to be renewed, as they no longer meet today’s standards. In addition, historical fixtures such as the solid herringbone parquet flooring in the apartments, which was partially covered with carpeting, need to be uncovered again and the damaged ceiling stucco needs to be replaced. Consideration should also be given to removing the plastic windows, as they do not match the historic appearance.

Two major new buildings are planned. On the one hand, an elevator is to be installed, which corresponds to the regulations of the monument protection, and on the other hand, the unused and completely desolate attic with the roof truss is to be converted into an apartment. When implementing the apartment conversion project, it will also be necessary to connect these to the gas central heating system, as currently only the store unit and the apartments on the 1st and 3rd floors are supplied with heat.Future use:

The property has been used as a residential and commercial building since its inception.

Videobeiträge:

Das European Heritage Project führt die Villa Kettenbrücke zurück zu altem Glanz

Baden-Badens Oberbürgermeisterin Margret Mergen im Gespräch mit Prof. Dr. Peter Löw

Das European Heritage Project erwirbt Schababerle-Haus in Baden-Baden

Kurator Peter Löw erklärt Grundsätze des European Heritage Projektes anlässlich des Richtfestes des Sonnenhofes in Baden-Baden