The Byzantine Gothic monument once served as a prestigious residence to the influential branch of the noble Tron family who lived near San Beneto.

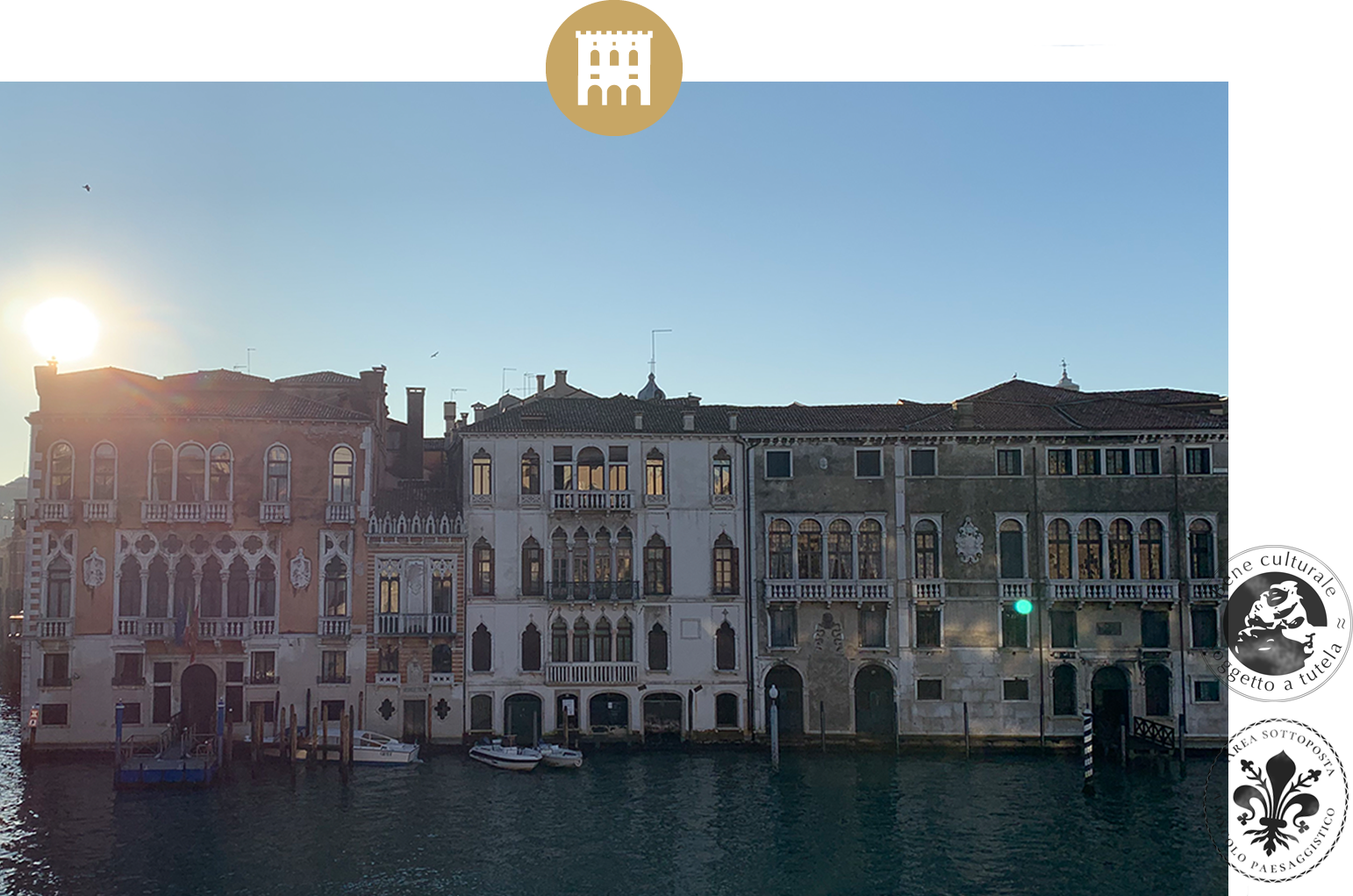

With a majestic view of the Rialto Bridge and direct access to the Grand Canal, the historic Palazzo Tron a San Beneto is located on San Marco, the administrative centre of the historic Republic of Venice. The ancient Byzantine Gothic monument once served as the prestigious residence to the more influential branch of the noble Tron family whose members held various important political offices throughout the history of the Republic. From 1471 to 1473, Nicolò Tron ruled as the 68th Doge of Venice and probably commissioned the reconstruction of the palazzo, adding two storeys to the building.

In 2018, The European Heritage Project acquired essential parts of the building, the piano nobile, the ground floor with garden, as well as parts of the attic from the noble Venetian Franchetti family.

The palazzo has a very rich history. The acquisition was marked by an awareness of the cultural treasures and historical relevance of the listed building.

MORE | LESS

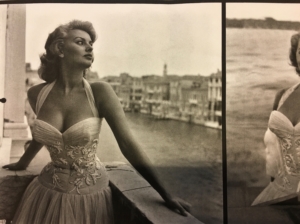

Sophia Loren resided in the Palazzo Tron A San Beneto while attending the 1955 Venice Film Festival. A photograph of the Italian film diva in one of her most epic poses on the balcony of the Palazzo overlooking the Grand Canal captures her visit for posterity.

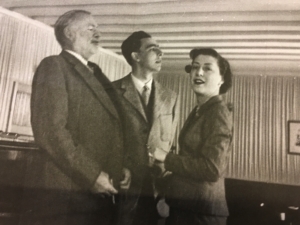

The American novelist Ernest Hemingway was a frequent guest in the 1940s and became a good friend of the former Palazzo owner Baron Raimondo Nanuk Franchetti. Franchetti served as a model and inspiration for the literary character Baron Alvarito in Hemingway’s novel “Across the River and Into the Trees” published in 1950.

The European Heritage Project is proud to be able to revive the original splendour and esprit of the Palazzo Tron A San Beneto. All renovation work, including technical, sanitary and electronic aspects, as well as the restoration of the entire façade, have been concluded.

As the palazzo is an essential part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, The European Heritage Project furthermore aims to support the revitalisation of the currently closed Chiesa di San Beneto. Once the confessional church of the Tron family, the sacral building is not only a direct neighbour of the palace, but also represents both its namesake and the patron saint of the district, Saint Benedict. Both the church and the palace still bear witness to the Doctrine of the Two Swords that dominated the beliefs of the ancient world.

PURCHASE SITUATION

After generations of ownership by the Venetian aristocratic Franchetti family, Baron Alberto Franchetti decided to sell the property when his children did not want to take over the city palace following his divorce. His personal goal was to hand over the family estate into good hands, and, in 2018, he sold Palazzo Tron a San Beneto to The European Heritage Project.

FACTS & FIGURES

Overlooking the famous Rialto Bridge, with several boat moorings and direct access to the Grand Canal, Palazzo Tron a San Beneto is situated in the centre of Venice on the island of San Marco. The four-storey city palace, built in the 13th century and rebuilt and extended in the 15th, 16th and 19th centuries, has a total living and usable area of 1,600 square metres including the magnificent piano nobile. The building, designed in the Venetian-Byzantine Gothic style, is near the Palazzo Fortuny Museum, the La Fenice Opera House and the Teatro Goldoni.

HISTORY

13th to 14th century: Economic upswing and oriental influences

The architecture of Palazzo Tron a San Beneto suggests that the palace ground floor and first floor were built in the 13th century at the latest, while the foundations are evidently older. Some of the bricks in the walls of the ground floor, which has meanwhile sagged heavily, date back to the late Roman Empire and were used in the architecture of Venice between the 9th and 13th centuries. Random samples taken from the façade showed that the palazzo is one of the oldest buildings on the Grand Canal.

The Gothic period reached Venice at a time of great prosperity, when the upper classes began to finance the construction of new churches and opulent mansions. Due to the proliferation of palaces being built, Venetian Gothic became a style in its own right. The creators of this new style, influenced by the Doge’s Palace, combined Gothic, Byzantine and Oriental elements to create a completely new and unique approach to local architecture.

The 14th century architects preferred the use of complex scale drawings, similar to those found on the symbol of Venetian Gothic, the Doge’s Palace. The fountain-shaped cistern still standing in the courtyard of the palazzo, built in 1319 and bearing the coat of arms of the Tron family, proves that the building was already part of the family’s property at that time.

After the Mongol conquests, Venetian merchants and merchants from rival cities made their way to Persia and Central Asia from about 1240 to 1360 as part of the so-called Pax Mongolica (Latin for “Mongol Peace”). There were small Venetian colonies of merchants in Alexandria and Constantinople. Venice’s relations with the Byzantine Empire were even closer and more complicated than those with Islamic-controlled territories, bringing with them many wars, but also promising economic and cultural contracts.

During this period, the Venetian economy was strongly linked to trade with the Islamic world and the Byzantine Empire; which is also reflected in the architectural style of Venetian Gothic, a style uniquely combining Northern European Gothic with Byzantine and Moorish characteristics. This stylistically exceptional potpourri is still visible today, especially on the façade of Palazzo Tron a San Beneto.

15th century: The ascent of the family of Tron a San Beneto

From the very beginning, the members of the Tron family occupied important positions within the Republic of Venice and sometimes served as procurators, senators and ambassadors. From the 15th century on, the family gained increasing importance as merchants and local rulers on Corfu and Crete.

The origin of the family is unclear. 18th century genealogists suspected that they were originally from Ancona. It is also believed that the Tron family built the demolished Chiesa di San Boldo in Venice in the 11th century. Furthermore, a certain Marco “Truno” was listed at the Venetian parish of San Stae in Venice in 1159. At any rate, the Tron family was among the so-called case nuove, the aristocratic, non-apostolic families of Venice.

The family branch of Tron a San Beneto originated when the family settled near the Venetian parish of San Beneto.

A major architectural change followed with the reconstruction of the palazzo under Nicolò Tron (1399-1473), the 68th Doge of Venice and most famous bearer of the family name, who had the residence extended by two storeys.

Nicolò Tron was the son of Luca Tron and had at least three brothers. He was married to Aliodea Morosini (†1478), who was popularly called “Dea Moro,” the black goddess. Dea was described by the chronicler of the Doge’s Palace to be the greatest beauty of the century. Legend has it that her beauty was of great importance for her husband to be elected as Doge due to the great beauty cult in Venice at that time. As the daughter of Silvestro Morosini, she belonged to an older and more powerful family than her husband Nicoló. Her coronation as Dogaressa was described as the most splendid in the history of Venice. Because of her modesty, she retired to a monastery after the death of her husband and, based on her vows, refused the state burial appropriate to her rank.

Dea and Nicolò Tron had two sons, Filippo and Giovanni. Giovanni suffered a terrible fate when he was quartered in 1471 in Turkish captivity.

Nicolò Tron was a merchant and had become very wealthy in a short period of time. He held several offices in the service of Venice. He was a consigliere in naval affairs and ambassador under Pope Pius II (1405-1464). In 1466, he was proclaimed Procurator of San Marco. Tron prevailed in the Doge’s election of 1471 against his later successors Pietro Mocenigo (1405-1476) and Andrea Vendramin (1393-1478), the 71st Doge of Venice. During his time as doge, the rule over Cyprus by Venice was consolidated, and disputes with the Turks were reduced by an alliance with the Iranian ruler Ulsan Hassan Beg (1423-1478). Through his skilful politics, he secured the republic a time of peace. However, the city’s indebtedness also increased sharply during Tron’s term, partly due to the expansion of the armoury, which had served as shipyard, armoury, and naval base of the Republic of Venice since the 12th century.

Tron also reformed the Venetian coinage system. He created a new coin, the Tron, depicting the Doge’s head in profile on the back in the style of antique coins, thus violating Venetian customs according to which any form of personality cult in connection with the Republic was rejected.The European Heritage Project has succeeded in acquiring an original coin, which is now on display in Palazzo Tron. After the death of Tron, the coin was withdrawn from circulation. The tomb of Nicolò Tron was built by his son Filippo in the choir of the church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in the district of San Polo. The sculptor and architect Antonio Rizzo (1430-1499) was responsible for the design and construction. According to its inscription, the monument was financed by the spoils from the Turkish wars.

17th-18th century: Promotion of the fine arts and the Caterina Dolfin scandals.

In the 17th century, the members of the Tron family still occupied important positions within the Republic of Venice, but increasingly began to dedicate themselves to the promotion of culture. In 1637, the brothers Francesco and Ettore Tron, also from the San Beneto branch of the family, founded the Teatro San Cassiano, the first public theatre in the world not solely for the nobility. Ordinary citizens, if they could afford the entrance fee, could now enjoy the opera for the first time, while the popular Commedia dell’arte was introduced to the nobility.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the diplomat, politician and agronomist Nicoló Tron (1685-1771), named after his ancestor, inherited the palace and bequeathed it to his eldest son Andrea Tron (1712-1785). Andrea was the procurator of San Marco, ambassador to Vienna, Paris and Rome, and one of the two main candidates for the election of the Doge in 1779. He lost the election due to the numerous scandals surrounding his wife Caterina Dolfin (1736-1793).

Both famous and notorious for her views, her work and her past, Caterina, historically speaking, can be considered the better known, if not more important, personality within this marriage.

For centuries, the Dolfin family was one of the most important Venetian patrician families, and, as a branch of the Gradenigo family, it was one of the twelve so-called “apostolic” families of Venice.

Caterina was the daughter of the nobleman Antonio Giovanni Dolfin and the noblewoman Donata Salamon, who also came from one of the oldest aristocratic families in Venice. Caterina’s father lost the family fortune during his lifetime and, with his death in 1753, left his wife and daughter in great debt.

In 1755, the young Caterina entered into an arranged marriage with Marcantonio Tiepolo, a member of another influential noble family who had the financial means to free her from her debts. There was much speculation in Venetian society about the marriage of Caterina and Marcantonio; it was assumed that Caterina had a love affair with Andrea Tron in 1756, only a few months into her marriage. Very soon after the affair began, Caterina filed for divorce and the affair became the subject of a major scandal. After years of litigation, the annulment was granted in 1772, whereupon Caterina married Andrea Tron, who used his marriage to enter the highest circles of Venetian society eventually holding the prestigious position of Procurator of San Marco.

In 1757 Caterina made her debut as a writer under a pseudonym. Her most famous work was a collection of sonnets inspired by her father and published between 1767 and 1768. She was at the centre of a circle of intellectuals and maintained a prestigious literary salon. In 1772 she was summoned before the Venetian Inquisition because some of the works in her library contained ideas of enlightenment.

However, Caterina Dolfin not only used her poetry, entertainment art and intellectual relevance to shock Venetian society; she is said to have had numerous affairs. One of her most famous lovers was probably the Duke of San Gabrio, Gian Galeazzo Serbelloni (1744-1802), who was eight years younger. According to their correspondence, which is still preserved today, the affair may have begun in 1773.

In 1778 Andrea Tron, Caterina’s husband, was elected Senator. However, he lost the Doge’s election in 1779 although he was one of the two main candidates. This was partly due to the scandals surrounding Caterina at the time, as well as her involvement in the Gratarolo affair, named after the Venetian Foreign Minister Antonio Gratarolo.

In 1775, a play, presumably commissioned by Caterina, revealed Gratarolo’s political intrigues and private affairs. In the same year that Andrea Tron applied for the Doge’s office, Gratarolo answered the insult with a revenge play that caricatured Catarina Dolfin and her social circle, exposed her love affairs, and publicly defiled her name and reputation. The play destroyed Andrea Tron’s chances of becoming Doge, although it turned out that the victorious candidate had a wife who, as a bourgeois and former tightrope walker, was even less suited to the title of Dogaressa.

Caterina Dolfin was widowed in 1785. She had inherited a considerable fortune but got into a quarrel with her former parents-in-law. In 1788, she finally moved from Palazzo Tron to her second home in Padua. In her later years, she worked on a project to reform women’s education, but it was never completed.

End of the 18th century and the 19th century: Many changes of ownership

When Chiara Tron, who was childless, died at the end of the 18th century, and the family branch of Tron a San Beneto died out, the property went in direct succession to the patrician family Donà Dalle Rose due to Chiara’s marriage. However, this led to inheritance disputes as the family branches of Tron a San Stae claimed the palazzo. Nevertheless, the Donà Dalle Rose family was able to assert itself in court against the Tron a San Stae family.

As a result, the palazzo, with the exception of the 2nd floor, was sold to the Vivante merchant family. The family had always been wealthy, but with the dissolution of the Republic of Venice in 1787, the city experienced a severe economic crisis. Only one branch of the Vivante family, the two sons, Lazzaro, called Mandolin Menachem, and Sabbato, managed to survive the crisis financially. One of the factors contributing to their success was the marriage policy of the family which joined another important high socio-economic Jewish family, Treves de Bonfili. The two sons married two of the daughters of Baron Giuseppe Treves de Bonfili (1794-1866). Both families were equally active in the maritime and insurance sectors. After the death of his brother, Sabbato continued the business and, in 1832, founded the Venetian branch of Generali Insurance Venice, then Assicurazioni Generali Austro-Italiche. He sold his stake in the insurance company to Spiridione Papadopoli (1799-1859) in 1848, one year before his death.

In the meantime, the Italian central bank, the Banca d’Italia, acquired the palazzo with the aim of establishing its head office in Venice, but at the end of the 19th century the property was sold to the Rocca family from Padua. The Rocca family had the palace restored on a large scale for the first time in centuries. The self-contained Corte Tron, the inner courtyard of the palazzo, including the elevator, was built during this period.

From the end of the 19th century until today:

Of expeditions, famous guests and ducks in the house of Franchetti

The Vivante line died out in the 19th century and Palazzo Tron a San Beneto passed to the Franchetti family, a Jewish family that had lived in Venice for many generations and one of the richest families in the Mediterranean since the 18th century. In the course of the equality policy in the 19th century, the family was elevated to the status of nobility. The marriage of Baron Raimondo Franchetti to Louise Sarah Rothschild (1834-1924) from the House of Rothschild in Vienna, enhanced the family’s reputation. The composer Alberto Franchetti (1860-1942) was born out of this marriage. His son Raimondo Franchetti (1889-1935) was to be remembered as the most famous member of the family. Until his death in a plane crash in the Egyptian desert, Raimondo Franchetti made a name for himself as an explorer studying ethnology and nature. His expeditions to North America, Malaysia, Annam (today a part of Vietnam), Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia and Sudan were photographed and filmed, making him particularly popular. He also documented the 1911 Revolution, also known as the Chinese Revolution or the Xinhai Revolution (1911/12), from the fall of the Chinese Emperor to the founding of the Republic of China.

In 1920, he married Countess Bianca Moceniga Rocca (1901-1958), whose family owned Palazzo Tron a San Beneto at the time, whereby the former family property of the Franchetti barons was returned to them.

Raimondo and Bianca Franchetti gave their five children the particularly exotic names Lauretana, Simba, Lorian, Afdera and Nanuk as a testimony to their love for distant places and foreign cultures. After Raimondo Franchetti’s death, his children established the Palazzo Tron a San Beneto as a lively social location. Numerous European and American film greats resided here, including Sophia Loren (*1934), when she was a guest at the Venice Film Festival in 1955. A photograph of the Italian film diva in one of her most epic poses on the balcony of the Palazzo overlooking the Grand Canal captures her visit for posterity. The American novelist Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) was also a frequent guest at Palazzo Tron a San Beneto in the 1940s and became a good friend of the former Palazzo owner, Baron Nanuk Franchetti. It became an annual tradition for Franchetti and Hemingway to hunt ducks together in Cortina d’Ampezzo after the summer in Venice. Franchetti served as a model and inspiration for the literary figure of Baron Alvarito in Hemingway’s novel “Across the River and into the Trees” published in 1950.

Afdera Franchetti (*1931) was very involved with the European jet set and the British aristocracy. Her marriage to Howard Taylor (1929-2017), the older brother of the film icon Elizabeth Taylor (1932-2011), introduced her to the circles of famous Hollywood stars. In the 1950s she met Audrey Hepburn (1929-1993), who, in turn, introduced her to Henry Fonda (1905-1982), 26 years her senior, and one of the most important actors in film history to this day. Afdera married Fonda in 1957 but they divorced in 1961 because the baroness felt that their age difference was too big.

THINGS TO KNOW & CURIOSITIES

Chiesa di San Beneto

The church of San Benedetto, popularly known as San Beneto, gave its name to the San Beneto branch of the Tron family. It is situated in the immediate vicinity of the palazzo, which is also named after the church. The sacral building has existed since 1013 and was initially the responsibility of the Benedictine monastery of San Michele di Brondolo near Chioggia. In 1435, the Bishop of Castello promoted the building to the classification of a monastery. Originally of modest size and built in the Romanesque style, the church faced east and consisted of three naves with a wooden roof.

The 17th century alterations changed the original orientation of the church towards the north, forming a single nave.

The present Baroque design dates from 1619 when the building was rebuilt by the Patriarch of Venice, Giovanni Tiepolo (1570-1631), who commissioned it because, according to documents, the building was severely damaged and at risk of collapse. The consecration of the church in honour of Saint Benedict took place in 1695.

The interior of the church contains works of art by famous Italian Baroque artists such as the Florentine, Sebastiano Mazzoni (1611-1678), Bernardo Strozzi (1518-1644) from Genoa, and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696-1779) from Venice.

The façade is divided into three parts by pilasters resting on simple plinths and ending with chapiters. On these, in turn, a cornice rests, which bears a beam with the inscription “D. BENEDICTO” engraved on its frieze. Immediately below is a Diocletian window. Two further small arched windows at the centre of the façade flank a portal with a triangular tympanum supported by a gatehouse.

Previously, there was a Romantic belfry to the west, which was higher than the building, also integrated into the façade, and could be seen from the courtyard of Palazzo Tron together with the conical roof of the tower.

A belfry of a much more modest size built in the 17th century is now situated in the northwest and is crowned by an onion dome.

San Beneto has since been downgraded from an independent parish to the vicarage of the church of San Luca and is currently closed for worship.

The libertine Conte Giuseppe Giacomo Albrizzi and Canova’s “Hebe”

In 1792, Giuseppe Emanuele (†1841) separated from his Jewish family because he insisted on his right to act as an independent entrepreneur. Even at a young age, he was considered more of a nonconformist character. According to numerous charges, Giuseppe Emanuele was investigated by the Inquisitors of the Republic throughout his life. Together with a Christian servant, he lived in the Jewish ghetto of Venice, where he kept books by Voltaire (1694-1778), works by Jean-Jacque Rousseau (1712-1778), and texts by the libertine, if not revolutionary, poet and former senator of Venice, Giorgio Baffo (1694-1768) in his library, documents that were considered “dangerous” at the time.

Two years after the “dissolution of brotherhood”, i.e. of his family, he converted to Catholicism. He was later ennobled and called himself Conte Giuseppe Giacomo Albrizzi. His considerable fortune enabled him to buy one of the floors of Palazzo Tron a San Beneto. Although the Jews of Venice had for centuries enjoyed far more freedoms, especially economically, than in other European states and principalities, and also enjoyed true protection against attacks as guaranteed by the Inquisition of Venice, they were never able to acquire real estate outside of the ghetto in the sestiere of Cannaregio. This changed, however, with the abolition of the ghetto under Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821).

With the conquest of Venice by the Napoleonic troops, all laws discriminating against Jews were abolished, the gates of the ghetto were burned in 1797, and the obligation to live in the ghetto was abolished. However, the Jews were not granted any other rights until 1848, when they became equal. Converts, such as Giuseppe Giacomo Albrizzi, were granted these rights as early as 1797.

The new landlord of the palazzo owned some works by the famous classicist sculptor Antonio Canova (1757-1822), which were exhibited in one of the salons of the piano nobile on the Grand Canal. His collection was admired by many, including famous visitors such as Holy Roman Emperor Francis II (1768-1835), and Louis I of Bavaria (1786-1868). In 1830, due to financial difficulties, he had to sell the most valuable piece of the collection, Canova’s Hebe, to Frederick William IV of Prussia (1795-1861).

The German poet Johann Gottfried Seume (1763-1810) wrote in his most famous work “Spaziergang nach Syrakus” (A Stroll to Syracuse) in 1802 about Hebe, the almost legendary statue representing the goddess of youth, which was shrouded in legend because of its perfect beauty:

I stood drunk on sweet intoxication,

As if immersed in a sea of bliss,

With reverence for the goddess there,

Who looked down on me,

And my soul was in sparks:

More than Amathusia was enthroned here.

I had escaped mortality,

And my glances of ardour

Out of her gaze Ambrosia drew

And nectar in the hall of the gods;

I did not know what happened to me:

And if Zeus were near with his lightning,

I reached for the scale, presumptuously,

With which she passes the deity,

And now, staggering perhaps, dared

Even to mock the Alcidine,

And with God to beat his reward

ARCHITECTURE

Architecture: Special conditions & Byzantine charm

Contrary to the common misconception that Venice’s buildings stand on shaky foundations, the foundations of Palazzo Tron a San Beneto confirm a fact that at least the local population is aware of: the foundations are very solid and, the older the building, the more firmly the pile structures, made of oak or elm wood, bricks and solid pietra d’istria, brace themselves into the sandy, muddy alluvial soil.

Originating from the Croatian region of Istria, Istrian stone, pietra d’istria, has been the most commonly used building material in Venice since the 13th century. On the one hand, it gives the typical white façades their characteristic appearance, as evident at the Palazzo Tron a San Beneto. On the other hand, it is a white limestone that looks like marble from the outside, but is, however, much denser, more porous, more flexible, less sensitive to acid and, with a compression density of 1,350 kilograms per square centimetre, extremely strong.

Nevertheless, the weight of the buildings sinking to the bottom of the lagoon has resulted in the structures sagging over the centuries, as is evident from the ceiling height of the first floor of Palazzo Tron a San Beneto. The height of the ceilings on the upper floors is more than three meters, whereas it has dropped to 2.10m on the ground floor. Used mainly as a boathouse today, the ground floor was originally used for business and storage purposes. These areas were originally called androne. Private life, on the other hand, took place on the upper floors. In addition, the ground floor is only partially subdivided into rooms. This was already so at the time of the original construction of the building, as regular flooding, or aqua alta, meant restrictions in terms of possible uses, and more walls meant the risk of promoting long-term water damage.

Overall, the Palazzo Tron a San Beneto, rebuilt for the first time in the 15th century by Nicolò Tron, is archetypal of Venetian-Byzantine Gothic architecture. The third storey was added in the 16th century and designed according to the principles of Sebastiano Serlios (1475-1554), one of the most advanced architects and important architectural theorists of his time, which is why it is essentially simpler than the lower floors. The use of a central serliana, a variation of the triumphal arch, is particularly striking. This is a portal vaulted by a round arch, flanked on both sides by narrower and lower rectangular openings. With its tripartite division, it is also reminiscent of a triptych framed by two arched windows on each side.

The flat ceilings and the flattened Roman roof, supported by clad wooden beams, are typical Venetian elements. They were preferred to vaulted ceilings popular elsewhere because they better withstood the vibrations of the moving foundation and generally minimised the risk of cracks in ceilings and walls.

Furthermore, the listed building captivates with its orientation, typical of Venetian city palaces, which differs fundamentally in its construction from the palaces in other Italian cities. For example, defence or the construction of ramparts was never an issue in Venetian architecture, which is why the Tron a San Beneto estate has direct access to streets and the Grand Canal. The water fountain in the courtyard of the property, dating back to 1319, was also publicly accessible in the Middle Ages when the palazzo was not yet surrounded by a wall. Today, the well has considerable traces of use, suggesting that hundreds of litres of water were pumped daily at the time. It only appears to be a well. It is, however, a covered cistern that, cut off from the salty groundwater and rainwater from the roof and courtyard, led via gutters to a sand filter system and finally to the actual cistern.

Today the property is enclosed by a wall built at the end of the 19th century by the Rocca family, and accessible via a back gate to the street. Two family coats of arms on the wall facing the street at the entrance to the courtyard still mark the rule of the estate by the Tron and Rocca families.

The town centre around San Marco, already densely populated at an early stage, led the Venetians to build high, as evidenced in the palazzo, as plots of land were few and far between and attempts were made to make the best possible use of the available space. Light could often only enter from the façade, which is why Venetian palazzi usually have more large windows than palazzi elsewhere. The gate, or portico, on the canal side enabled boats and gondolas to be easily and safely loaded and unloaded on site. A major change that took place in the 15th century was the alteration of the proportions of the central hall in the piano nobile. This hall, also called portego, was changed into a long passage. The core of the piano nobile is in a centrally oriented T-shape, with the portego starting from the courtyard side and ending in three larger salons on the canal side, which were used for social and festive occasions.

The keel arched windows of the palazzo mark the beginning of a stylistic development of the Venetian-Gothic arch, which is by far the most typical feature of Venetian architecture. Curved style gradients are also reflected in the façade of the storeys built at different times. On the ground floor, the oldest part of the building, only classical Gothic round arch portals are visible; supporting columns are completely absent.

However, these whimsical keel arches are not purely decorative. Whereas traceries only supported church windows in northern Europe, Venetian traceries serve an additional static purpose and also carry the weight of the supporting outer walls. Therefore, the relative weight carried by the traceries alludes to the relative weightlessness of the entire building. This, and the reduced use of load-bearing walls associated therewith, lends the Venetian Gothic style palazzo lightness and grace in its structure. Venetian Gothic, exemplified here, was far more complicated in style and design than earlier types of buildings popular in Venice, but never allowed for superfluous weight or disproportionality. Furthermore, the building was built to be as light, high and space-saving as possible, as every centimetre of land was precious due to the canals running through the city.

Overall, the influence of Moorish architecture on Venetian architecture is clearly reflected in the ornamental windows and the purely decorative battlements along the roof line. Byzantine and Imperial Roman architecture were also influential. This is easily recognisable in the coloured columns on the outer wall on the first and second floors of the façade. Interestingly, each column is different in shape, ornamentation and colour due to the fact that Venetian merchants and sailors brought back several columns from the Orient and the Mediterranean to the Republic, which had previously been used to stabilise loaded ships, but for which they had no further use. A prominent example of a columned façade can be found in the case of the western front of St Mark’s Cathedral facing St Mark’s Square, which was also built in the 13th century.

STRUCTURAL CONDITION AT TIME OF ACQUISITION

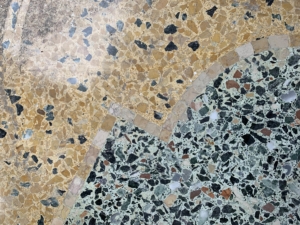

At the time of the acquisition by The European Heritage Project in 2018, the façade of the palazzo was in need of comprehensive renovation, as were the entire electrical and water supply systems. However, the restoration of various handicrafts, such as stucco work on ceilings and walls, the elaborately designed terrazzo floor, and some decoratively painted coffered ceilings, were given priority right the outset. A breakthrough in the ceiling in the piano nobile posed a particular problem since the entire ceiling threatened to collapse. An additional problem was the dilapidated areas in the heavily sunken and saltwater damaged ground floor.

RESTAURATION AND CONSERVATION MEASURES

Since the acquisition of Palazzo Tron a San Beneto in 2018, The European Heritage Project has restored the Venetian city palace at great expense. During the restoration work, the stylistic diversity, which testifies to the different phases of Venetian Gothic, proved to be both challenging and enriching. In particular, the pile construction method, the use of local materials and techniques, and the adaptation to the lagoon climate provided The European Heritage Project with entirely new insights into monument protection.

The work was completed in 2020. The façade has been completely renovated, the gardens and traffic areas have been overhauled and refurbished, and the interior has been entirely renovated in consultation with Bene Culturali. Only the boat berths and the jetty are still to be installed.

Statics

The statics, the roof truss, and beam constructions of Palazzo Tron were in good condition, but there remained some weaknesses which were remedied. Some non-loadbearing, plastered wooden walls were stripped, straightened and replastered. Some heavily bent, exposed load-bearing wooden beams on the ground floor were statically straightened and partly replaced.

A ceiling breakthrough in a salon of the piano nobile was particularly unfortunate. The ceiling was reconstructed as it threatened to collapse entirely. The breakthrough was caused by an excessive load, as unauthorised additional concrete was laid on the upper floor in the 1980s; an enormous weight for which the ceiling construction was not designed.

Roof and truss

At the time of the acquisition by The European Heritage Project, the roof structure was in perfect condition; only the roof cladding had to be renewed. The decision was made to remove most of the serviceable roof tiles, clean them and relay them, thereby restoring the roof to its original state.

Heating, electrical and plumbing systems

In all apartments, the power lines, sanitary facilities and water pipes were entirely relaid for the first time since the 1970s to make living in the building safer and to meet current standards in terms of sustainability and energy efficiency.

Reconstruction

Floors

The 18th century stone terrazzo floors in all the living spaces have been retained, damaged elements restored and missing ones added. The majority of the anthracite-coloured, heavy-duty granite chipping flooring in the smaller rooms and corridors was restored with minimal effort and greying was removed. The original floors in the large salons of the piano nobile, which were seamlessly cast ortsterrazzi, posed a particular challenge. Heavily damaged and fragile parts had to be completely and extensively restored. The original beauty of this special “terrazzo alla veneziana”, with its elaborate patterns of marble, limestone, dolomite, and concrete mixtures containing clay in iridescent colours of beige, ochre and jade tones, was to be preserved – a very elaborate process.

Doors, windows, water access

The flamboyant cast iron lattice windows and gates on the ground floor are very rusted due to the weather. In part, the rust was removed by grinding, brushing and high-pressure cleaning, but in part the corrosion damage was so advanced that the cast iron was so brittle and porous that individual elements had to be replaced completely. An experienced blacksmith, working according to original 18th century methods, was commissioned to carry out the necessary reconstruction. On the upper floors, the windows and galleries facing the courtyard were restored with a great deal of attention to detail. The wooden window frames, shutters, glass and cames from various eras were retained in their entirety but were fitted with double glazing for insulation purposes. All doors, including the wing doors of burl wood throughout the piano nobile, were sanded and polished, fitted with new hinges, offset and adjusted.

In addition, the non-existent jetty to the Grand Canal, which had become dilapidated over the last decades and was removed by the previous owner due to the strong decay, is to be reconstructed to allow safe access to the water again and to facilitate transport to the palazzo.

Masonry and Façade

Initially the façade of the palazzo, made exclusively of white pietra d’Istria, a particularly resistant limestone, was cleaned and, individual decorative but also load-bearing elements such as columns, window arches, balconies and ornaments were stabilised.

All in all, as is generally the case in Venice, the masonry exhibits salinization and mineralisation damage. One advantage of this is that the hygroscopic salt ensures a dry atmospheric environment and thus no moisture damage or mildew growth was detectable in the entire palazzo. However, the salinization also means that individual un-plastered bricks need to be replaced at regular intervals. The corrosion of the bricks due to the salt air was clearly visible especially on the ground floor. While the orange-coloured bricks that were used within the last one hundred to two hundred years are strongly porous, the ochre-coloured to yellow bricks, manufactured at time of the Roman Empire and older than a thousand years, have withstood all weather conditions.

On the ground floor towards the canal entrance, some dismantling took place as the originally spacious storage and boat room was subdivided in the 20th century.

Restorations (art & craft, stucco, frescoes etc.)

Damage to the ceiling stucco, the interior wall decor, and chipped and faded wall paintings in the piano nobile, dating from the end of the 19th century, have been repaired and restored by an experienced Venetian restorer. To ensure the greatest possible historical authenticity in the restoration measures, colour and pigment examinations were carried out. These examinations revealed that the nuances of today’s colouring differ from the original state. For example, some of the ornaments were originally pale green, but were later painted crystal blue. The basic hue of all the walls also differed. It was discovered that during the last renovation work, taupe gave way to a cream hue. Historical decor from the 19th century was chosen. The ornamental paintings on the ceiling beams and wooden cassettes on the ground floor as well as in the staircase, which can be classified in the early Byzantine Gothic period due to their variety of colours, were also restored.

PRESENT USE & FUTURE PLANS

As an active contribution to the preservation of Venice as a lively city, the Palazzo Tron a San Beneto is to be retained as a residential building. Its origins as a place of inspiration and social exchange should also be preserved. It is therefore planned to use the palazzo for cultural events, for example as an exhibition area for the Venice Biennale.

In addition, The European Heritage Project intends to provide financial and organisational support for the revitalisation and restoration of the Chiesa di San Beneto built in the 11th century. As the former confessional church of the Tron family, the ecclesiastical building is the direct neighbour of the palazzo.

Videobeiträge:

2018 erwirbt das European Heritage Project zwei Palazzi am Canal Grande in Venedig. Mit einem privaten Konzert des Münchner Knabenchors und des Opernsängers Kevin Connors feiern circa 80 geladene Gäste den Abschluss der Sanierungsarbeiten.