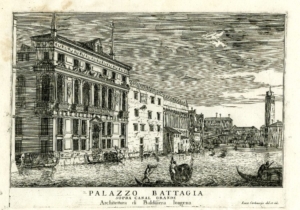

Located in the Venetian district of Santa Croce, Palazzo Belloni Battagia, with its richly decorated stone façade, is certainly one of the most beautiful palazzi on the Grand Canal.

Located between Fondaco del Megio, Venice’s old millet warehouse, and Palazzo Ca’ Tron, Palazzo Belloni Battagia offers a direct view of Palazzo Ca’ Vendramin Calergi on the opposite side of the Grand Canal, where the famous Venice casino is located.

Designed and built for the patrician family Belloni in the 17th century by Baldassare Longhena, the very architect of the Venetian landmark Basilica di Santa Maria della Salute, the palazzo has been listed as one of Santa Croce’s most important monuments.

Even today Palazzo Belloni Battagia impresses the onlooker with its opulent brilliant white façade. Especially the two obelisks that adorn the roof and give it a majestic frame form a graceful and unique sight found nowhere else along the Grand Canal in the UNESCO World Heritage Site.

MORE | LESS

It is nevertheless a deceptive charm which, in the long term, threatens the entire building fabric.

PURCHASE SITUATION

Up until 2018, the Instituto nazionale per il commercio estero (International Institute for Foreign Trade) was located on the lower floors of the palazzo while the rest of the building was used for private purposes. Parts of these room, especially in the mezzanine were misused, as the first floor belonged to a group of heirs who had rented out the living space as holiday apartments for several years but had not maintained the apartments properly.

After holiday rentals were no longer possible and the institute moved out, there were disputes among the heirs. The situation was made worse by the structural condition of the building. The Sopraintendenza demanded considerable investment in the structure which the heirs could not and would not support.

Faced with this situation, the heirs approached The European Heritage Project. Due to the urgency, The European Heritage Project acquired considerable parts of the palazzo on different levels in a short time and began the safeguarding and renovation process.

REAL ESTATE FACTS

The 17th century Baroque Palazzo Belloni Battagia, designed by Baldassare Longhena, is not far from the Chiesa di San Stae (the church of San Stae, an abbreviation for Saint Eustachius) in the Santa Croce district. Built on the Grand Canal, it is situated between the Fondaco del Megio and Palazzo Ca’ Tron, and opposite the Palazzo Ca’ Vendramin Calergi, which houses the casino of Venice.

HISTORY

17th century: From a gothic ruin to an imposing Baroque palazzo

The design and style of the architect Baldassare Longhena (1598-1682) was revolutionary and differed vastly from that of his mentor Vincenzo Scamozzi. Longhena’s buildings marked an important turning point in the history and architecture of Venice, heralding the end of the plague and the Byzantine Gothic period. The master architect is known to this day as the protagonist and pioneer of Venetian Baroque. Longhena’s repertoire consists mainly of sacral buildings and he was hardly involved in the construction of palaces or villas during his lifetime. This makes Palazzo Belloni Battagia on the Grand Canal a rarity.

After the end of the plague and due to the decline of the maritime trade, “La Serenissima” developed from a port city in the classical sense into a flourishing cultural metropolis. Venice’s hierarchically structured class society also changed during this period. Merchant families, for example, soon became equal in social status to the old aristocracy. Originally from Lombardy and related to the famous Milanese patrician family Sforza, the Belloni merchant family was incorporated into the Venetian aristocracy in 1647.

In addition to being merchants, the Belloni family was known as a dynasty of successful lawyers. In order to build a new noble residence in the heart of the city, the head of the family, Bortolo Belloni, acquired a dilapidated Gothic residence on the site of today’s Palazzo Belloni Battagia. He commissioned Baldassare Longhena to carry out the reconstruction of the 13th century building. In approximately 1648, construction of a residence for the Belloni family began, according to the designs of the renowned architect, on the remains of the Gothic building. The construction work was difficult and protracted. The family miscalculated the cost of the imposing reconstruction and had to spend all their assets in order to complete the work, which was repeatedly delayed. It took a total of 15 years for the palace to be completed in its present Baroque form.

The construction of the city palace almost drove the Belloni family into financial ruin, which is why they were forced to rent out the living space of the generously designed building during the conversion work and never resided in the palace themselves. Soon after the completion in 1663, the family sold the property to the Battaglia family, admitted to the Venetian patriciate in 1500, from Cotignola in Romagna.

19th century:

In 1804, Palazzo Belloni Battaglia passed to the wealthy merchant Antonio Capovilla, who had the interior of the palace refurbished in the classicist style. Capovilla’s improvements were strongly criticised at the time, as he erected a chapel on the ground floor, and added numerous frescoes by Giuseppe Borsato (1770-1849), as well as late Baroque and neoclassical murals by Giovanni Battista Canal (1745-1825) to the interior walls. Giuseppe Borsato was a painter, stage designer, scenographer and graphic artist, and was especially known for his Venetian veduta and his work at the renowned opera house Teatro La Fenice.

THINGS TO KNOW & CURIOSITIES

From the plague to the Venetian Baroque of Baldassare Longhena

In the early 17th century, patrician Venice was a city of prosperity, magnificently staged wealth, and cosmopolitan interaction. At the time, people from the Orient, the former Byzantium, Africa, and the whole of Europe lived in the city, and freedom of religion had high priority. But this freedom and economic prosperity, unknown elsewhere, also involved a great risk: Venice, as the major trading gateway between the Orient and the Occident, with ships and delegations from all over the world calling at its ports, was struck by the plague more than twenty times between the 14th and 16th centuries. The Venetian government established the strictest precautions and sanctions in Europe against the plague, including the construction of the Lazzaretto Vecchio on a remote island west of the Lido, the world’s first quarantine station.

When, in June 1630, one of the Duke of Mantua’s diplomats and his entourage brought the plague back to Venice, the city was to suffer the most devastating plague epidemic ever. The Venetians fought against the Black Death for three years, a struggle in which 46,000 people, a third of the total population, lost their lives.

In the autumn of 1630, the Doge Nicolò Contarini (1552-1631) promised the Blessed Virgin Mary a church in her honour, asking her to end the epidemic. The church was to be erected in an exposed location on the Bacino di San Marco opposite the Doge’s Palace. Baldassare Longhena (1598-1682), a pupil of the Renaissance architect Vincenzo Scamozzi (1548-1616), emerged victorious in the contest. The construction of the church initiated a fundamental urban reorganisation of the area on the other side of the Grand Canal which was to have a lasting effect on the image of Venice. After the end of the plague, Longhena began building the church of Santa Maria della Salute. He worked for the rest of his life, with a few interruptions, on the construction of the church, which was only consecrated in 1687, five years after his death. The church, one of his most important works, was inspired not only by his master Scamozzi but also by Andrea Palladio (1508-1580), the most important architect of the Renaissance in Northern Italy. The entrance area of Santa Maria della Salute, based on a Roman triumphal arch, was later copied in the design of numerous churches and cathedrals, both in Venice and elsewhere.

ARCHITECTURE

Although there is no clear documentation of the history of origin, and neither sketches nor blueprints exist, various art historians and architectural theorists agree that Longhena is architect. Many distinctive elements, especially when combined, support this hypothesis. The interrupted tympani, the lion-shaped protomes on the water surface which seem to support the entire building and thus achieve an almost floating effect, a construction method Longhena had already used before in Palazzo Pesaro, the refined stone panels, and the precise and elaborate material processing methods are elements that clearly point to the work of Longhena.

Viewed from the Grand Canal, the palace is recognisable by its two obelisks, symbolic of the Supreme Command of the Navy, and also found in the vanitas symbolism popular in the Baroque period. Inside the palazzo there are frescoes by Giuseppe Borsato and Giovanni Battista Canal which were created during the renovation of the palazzo in the 19th century. The interior design of the main floor stands out particularly due to two motifs: a 19th century fresco circle, still in very good condition, and a chapel built from a small oratory. The votive chapel houses an altar, and the walls and ceilings are painted in tempera. The forum with its high ceiling and various temple-like busts and columns, which can be seen from the first floor through a U-shaped gallery, is also a strikingly beautiful element. The forum and the gallery together provide a special lightness in this architectural interplay.

In addition to the functional ground floor, the palazzo has three full storeys and is particularly striking for its typically Baroque façade featuring a rich sculpture decoration. Baldassare Longhena used a system of numerous non-orthogonal axes. To this day it is unclear whether Longhena intentionally incorporated visual axes into the concept of his works or whether they are perhaps a by-product of his complex geometry.

The ground facade has a balustrade, in the middle of which there is a large arched portal with a roof. Above are six small square windows. The higher part has seven richly decorated rectangular windows, and two large coats of arms on the wall panels in between. The sub-roof is accessible, and the edge of the roof displays a serrated cornice with a long frieze featuring the Belloni family coat of arms. On the roof are two symmetrical, obelisk-shaped pinnacles, a peculiarity that can only be found in a few other palaces in the city, such as Palazzo Giustinian Lolin and Palazzo Papadopoli, also designed by Longhena. From the street, on the righthand side, the protrusion of the votive chapel on the main floor can be seen underneath the chimney on the second floor.

STRUCTURAL CONDITION AT TIME OF ACQUISITION

When The European Heritage Project acquired parts of Palazzo Belloni Battaglia in 2018, the affected apartments were in an extremely neglected state due to having been used as holiday apartments. Some rooms had to be cleared out, and the windows did not close properly causing a constant draught. Some of the interior structure had been altered during illegal remodelling in the 1950s. The electrical system was in a dilapidated state.

The ground floor displayed severe flood damage. There was no septic tank system and wastewater merely flowed into the lagoon.

The most extensive damage was to the lavishly designed pietra d’istria façade. The façade had sunk considerably towards the Grand Canal and threatened to collapse. The supervisory authorities had issued an urgent directive for the immediate restoration. In addition, the originally white façade was so blackened with dirt that cleaning and sealing was unavoidable.

RESTORATION & CONSERVATION MEASURES

The European Heritage Project and the owners drafted a redevelopment plan together with the supervisory authorities and the monument preservation authorities. The first priority was to secure and clean the stone façade. The restoration work has already begun and is expected to be completed by mid-2021.

Simultaneously, the flood-damaged first floor was overhauled. The plaster that had flaked off over large areas was repaired. At the request of the authorities, barely visible wall cladding was installed at a height of two meters to safeguard against further flood damage. The gates on the canal side have been professionally restored.

The interior of the acquired parts had to be completely overhauled. Thick layers of salt had formed behind the wall cladding. A new solution was sought to ensure adequate ventilation behind the walls. Sanitary outlets had to be created and the sewage now accumulates in a modern septic tank systems. Heating, air conditioning, sanitary facilities and electrical systems were entirely reinstalled. All windows and doors were restored where possible.

Reconstruction

Floors

The parquet floors, mostly original, represent a special feature of the building. They were professionally removed, restored, and reinstalled in place. Their rich ornamentation reflects the lifestyle of the 18th and early 19th centuries. The remaining softwood floors and solid wooden floorboards in the adjoining rooms were severely damaged, but were fully restored.

The black and white 19th century tiles in the entrance were degassed, straightened and re-laid.

Doors and windows

The wooden window frames, shutters and glass have been entirely restored taking the latest energy aspects into account.

All doors, including various hinged doors, were removed, sanded and polished, fitted with new hinges, re-fitted and adjusted.

Restorations (art & craft, stucco, frescoes etc.)

To ensure the greatest possible historical authenticity during the restoration measures, various material examinations were carried out throughout the affected parts of the palazzo. The stucco profiles on the ceilings of the salons in the acquired apartments have been preserved and safeguarded with great expenditure of time and material. The massive door frames and tympani made of delicate rose-coloured Rosa Asiago marble were also preserved.

Many of the Baroque ornamental elements on the façade, as well as supporting elements such as columns and arches as well as the obelisks, were extensively repaired and stabilised after correcting the static defects.

The blackened façade has been cleaned in 2021.

All remaining work was completed in 2023.

Since the work was completed in 2023, the Palazzo has been used for cultural events, such as classical concerts, but also for exhibitions. Meetings and art gatherings take place here, particularly as part of the Biennale. The rooms on the Belle Etagen can also accommodate up to 10 people.

PRESENT USE & FUTURE PLANS

The European Heritage Project plans not to allow the acquired parts of the building to be used for commercial purposes, even if this would certainly be more profitable.

In future, cultural events such as classical concerts could take place on the European Heritage Project floors. These areas are to become an open forum for exhibitions and events, for example as part of the Venice Biennale.

Videobeiträge:

2018 erwirbt das European Heritage Project zwei Palazzi am Canal Grande in Venedig. Mit einem privaten Konzert des Münchner Knabenchors und des Opernsängers Kevin Connors feiern circa 80 geladene Gäste den Abschluss der Sanierungsarbeiten.