As the highest secular building in the city, constructed to demonstrate institutional power and economic influence, the free-standing Berggericht has always shaped the historic cityscape.

In 2012/13 The European Heritage Project managed to acquire an important part of the old town of Kitzbühel, namely the old Berggericht building and the so-called Lacknerhaus.

Like Kitzbühel’s entire medieval town centre, the 16th century Berggericht, the historical mining court, alongside the 17th century Lacknerhaus, impress with their simple practicality which is characteristic of the local angular and massive architecture of secular buildings. As an ensemble, the buildings, which together with St. Catherine’s Church dating from the 14th century form St. Catherine’s Square (Katharinenplatz), the impressive core of the historic old town of Kitzbühel.

As the highest secular building in the city, constructed to demonstrate institutional power and economic influence, the Berggericht, in particular, has always shaped the historic cityscape. In its judicial function as a mining court, this official building was always a highly influential force determining the town’s economic, cultural, social and political climate over three centuries. As the highest local authority, the Berggericht was responsible for silver mining which contributed significantly to the wealth of the entire Kitzbühel region during the Middle Ages.

Since The European Heritage Project acquired these two listed secular buildings in 2012/13, the former Berggericht has shed its dreary, grey and neglected exterior. Prior to the acquisition, the building stood vacant for a decade resulting in massive deterioration in the building fabric. Broken windows, birds nesting in the roof, and an overall disastrous condition was remedied by extensive restoration work, and its original and imposing late-Gothic appearance restored. All historic details, from Gothic vaulted ceilings to Renaissance frescoes and Baroque windows, which were either augmented or retained over the centuries, have been restored.

The Lacknerhaus, historically a private residence and commercial building, was dilapidated and uninhabitable. The building stood empty for decades. Over the years it had degenerated to become the town centre’s eyesore.

After lengthy bureaucratic procedures, the extensively planned restoration of the building is finally in the final phase which is expected to be completed by the middle of 2021.

By acquiring and restoring these two listed buildings, The European Heritage Project contributed to a process by which the oldest, but neglected, part of the old town of Kitzbühel has regained its historical significance.

PURCHASE SITUATION

Berggericht

Since 1935 the tax office of the city was housed in the former Berggericht building. In 2002, however, due to high maintenance costs, the local authority moved to a new building outside the historic city centre. As a result, the Federal Government decided to auction off the listed building. However, the city of Kitzbühel, one of the bidders at the auction, was outbid by a local entrepreneur.

The new owner had intended installing an elevator visible from the outside of the building, which the town and the monument preservation authorities did not want to approve. With the aim of putting the authorities under pressure, the new owner abandoned all restoration work and refrained from carrying out any required maintenance work himself. The building remained vacant.

After suffering substantial damage due to 10 years of acute neglect, and the Gothic vaults in particular being threatened, The European Heritage Project became aware of the situation and was ultimately able to convince the owner to sell the building to The European Heritage Project in 2012.

Lacknerhaus

By the beginning of 2013, the first signs of the successful restoration measures at the Berggericht were already visible. Having become aware of this and impressed by the close cooperation between The European Heritage Project, the federal heritage authorities, and the municipality of Kitzbühel, the owner of the Lacknerhaus contacted The European Heritage Project. As the owner could not afford the urgently required renovation of the listed building, he offered to sell it to The European Heritage Project. At this time, the Lacknerhaus had been empty for an extended period.

REAL ESTATE FACTS & FIGURES

.

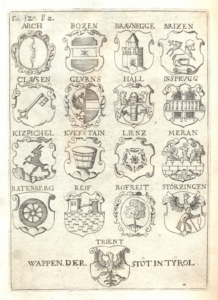

Kitzbühel is a medieval town situated in the Kitzbühel Alps along the river Kitzbüheler Ache in Tyrol, Austria, about 95 km east of the provincial capital Innsbruck and is the administrative centre of the Kitzbühel district. The glamorous city is internationally known as one of the most important alpine winter sports locations.

Kitzbühel has always been the economic and cultural centre of the region, due primarily to the silver mining which had given the city importance and wealth since the Middle Ages. The Berggericht and the Lacknerhaus still bear witness to this today.

The uniqueness of the 16th century Berggericht, is due not only to its distinctive history but also to its special location. The building was not structurally integrated into the row of buildings, like the other houses in the rest of the medieval town centre of Kitzbühel; instead, it is free-standing and is the second tallest building after St. Catherine’s Church, with which it forms a historically significant ensemble on St. Catherine’s Square, as does the Lacknerhaus, also acquired by The European Heritage Project.

The Gothic four-storey former courthouse has a floor area of almost 800 square metres and is 24 metres high.

The adjacent four-storey Lacknerhaus, built at the beginning of the 17th century, is characterised by a rectangular floor plan, and comprises a living and usable area of 350 square meters.

HISTORY

Around 1178, the name Chizbuhel is mentioned for the first time in a document belonging to the Chiemsee monastery (where it refers to a “Marquard von Chizbuhel”), whereby Chizzo refers to a Bavarian clan and Bühel refers to the geographic location of a settlement on a hill. A hundred years later, a source attests to the existence of a bailiwick (Vogtei) of the Prince-Bishopric of Bamberg in Kicemgespuchel and, in the 1271 document elevating the settlement to the status of a town, the place is called Chizzingenspuehel.

Kitzbühel became part of Upper Bavaria in 1255 with the first Bavarian division of the land. Duke Ludwig II of Bavaria (1229-1294) granted Kitzbühel town rights on 6 June 1271 and the town was secured with fortification walls. As Kitzbühel established itself as a trade and marketplace in the centuries to follow due to its location between the Thurn Pass and the Chiemgau region, and grew steadily and was unaffected by war and conflict, the walls at the level of the first storey were removed and used to accommodation.

The marriage of Countess Margarete of Tyrol (1318-1369), nicknamed Margarete Maultasch, to the Bavarian, Ludwig der Brandenburger (Louis V, Duke of Bavaria) (1315-1361) in 1342 temporarily united Kitzbühel with Tyrol, making the city a Bavarian protectorate until Ludwig’s death. After the Treaty of Schärding in 1369 ended the disputes between Bavaria and Austria in the struggle for rule over Tyrol, Kitzbühel was returned in its entirety to Bavaria. Due to the division of Bavaria, Kufstein fell to the Landshut line of the House of Wittelsbach.

During this time, silver and copper mining was systematically promoted in Kitzbühel and comprehensive mining rights were issued which would later become important for the entire Bavarian duchy. In 1504, Kitzbühel went to Tyrol permanently. Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor (1459-1519) had requested this in return for his arbitral verdict which ended the Landshut War of Succession, a feud between Bavaria and the Palatinate, in 1505.

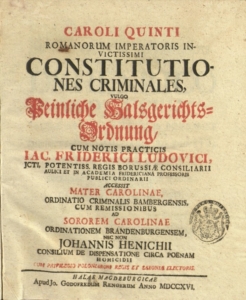

The Oberbayerisches Landrecht (Upper Bavarian land law) issued by Louis IV, or Ludwig der Bayer, in 1346 continued to apply to the judicial districts of Kitzbühel, Kufstein and Rattenberg until the 19th century, with the result that these three areas occupied a special legal position within Tyrol.

Maximilian enfeoffed Kitzbühel, and it came under the rule of the Counts of Lamberg at the end of the 16th century, until the last remnants of feudal rule were solemnly abolished on 1 May 1840.

The wars of the 18th and 19th centuries bypassed the town, although the Kitzbühel citizens took part in the Tyrolean liberation struggles. Kitzbühel again became part of Bavaria when Emperor Franz I (1768-1835) ceded Tyrol to Bavaria in the Treaty of Pressburg in 1805.

After the fall of Napoleon (1769-1821), the region was reunited with Austria at the Vienna Congress in 1815.

When Emperor Franz Joseph (1830-1916) finally regulated the confused constitutional conditions and the Salzburg-Tyrol Railway was completed in 1875, the city experienced an economic and industrial boom. In the 20th century, Kitzbühel became a place for the rich and beautiful, where many celebrities lived.

Kitzbühel was fortunate to be spared destruction during the First and Second World Wars, which is why the historic city centre around St. Catherine’s Church, including the medieval city walls, is still preserved today.

Berggericht

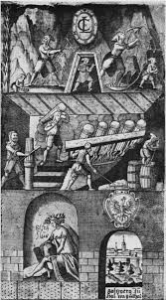

The Berggericht was the prestigious courthouse and the administrative building responsible for silver mining, which in the Middle Ages had contributed significantly to the wealth of the town of Kitzbühel.

Tyrol was one of the few Alpine countries to have silver and copper ores worth mining. As a result, the economic and political power of the sovereigns grew. The rise of the House of Habsburgs to world power at the turn of the 15th to the 16th century would not have been possible without the silver and copper from the Tyrolean ores. In addition to the wealth of ore in the Schwaz region, Kitzbühel was the most important mining centre. The town owes its importance and rise to mining.

The prestigious secular building was first documented in 1535 as the home of Ruepprecht Humbpühler and his wife Martha Wonnherrin. In the following period, there were several short-term owners, whereby a certain Sigmundt Neissl, also known as Neussl, was named as a new owner for the first time in 1543. In 1562, the “Neisslhaus” was leased by the mining authority for the Bergrichter, and purchased the building in 1587. From then on, the mining law was exercised according to the Codex Maximilianeus Bavaricus Civilis, also commonly known as the Bavarian Land Law.

The Berggericht was a court responsible for matters relating to mining law, arbitration and the investigation of accidents in mining associations, supervising concessions and representing the legal rights of the sovereigns. For example, the mining areas of Röhrerbühel and Jochberg, in particular the local copper and silver ore mines, as well as the processing of extracted metals and the sale of the products, were subject to the Berggericht of Kitzbühel.

The official authority was exercised by the Bergrichter (mining judge), and the Berggeschworenen as jurors. Everything was documented by the Berggerichtsschreiber (mining court clerk). The function of the Bergrichter was assumed either by the Bergamtsverwalter (mining office administrator), the Bergvogt (reeve or magistrate) or the Bergmeister (mining master). The mining jurors also supervised the ore mines as well as the Pingen (wedge-shaped, ditch-shaped, or funnel-shaped depression in the terrain) that resulted from mining activity. Further aides of the mining court were the Forstmeister (head of forestry), and the Fronbote (court usher or messenger) who was responsible for the execution of the court judgments and for other messenger services. The Fröner (bailiff) and the Silberwechsler (silver changer) had to meticulously document and check the transactions and the taxes payable to the sovereigns.

The following Bergrichter are mentioned in several documents throughout the history of the building: Carl Ruedl in 1631, Mathias Undterrainer in 1645, and Sebastian Undterrainer in 1671. A Georg Budina is mentioned as a Bergrichter and Waldmeister in 1692.

After the closure of the Kitzbühel Berggericht at the end of the 18th century, the building, still known as the Berggerichtshaus, was the official seat of the substitution of the Kitzbühel Berggericht, and of the Kitzbühel Waldamt (forestry office). From 1818 onward it was probably only the seat of the Waldamt. It later became the seat of the tax authority from 1936 until the tax office moved in 2002.

Lacknerhaus

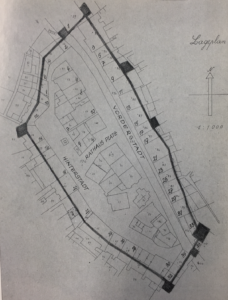

The Lacknerhaus at Hinterstadt No. 17, named after its last owner Jakob Lackner, dates to the beginning of the 16th century. Like the building at Hinterstadt No. 19, the Lacknerhaus has belonged to the building at Vorderstadt No. 20 since the beginning of the 17th century, as can be seen on historical town plans drawn around 1620.

When the leather master Veit Koidl acquired the building in 1819, it was separated from the building at Vorderstadt No. 20, and from then on had the address Hinterstadt No. 17. The simple late-Gothic building subsequently experienced a lively change of ownership and inhabitants. The next owners were Maria Koidl in 1827 and her Oberwald heirs in 1856. In the same year, the Stöckl building, as it was called at the time, passed to Bartlme Stangasser. He had the building, known as the “Lintnerhausstöckl”, rebuilt and enlarged, whilst retaining the 16th century core. In 1857, Anton Seiwald, the bricklayer of the “Klosterfrauenhaus”, leased parts of the premises of today’s Lacknerhaus. A change of ownership is documented in the same year, with the acquisition of the building by the beltmaker and gold smith Anton Webersberger. In 1889, his wife Magdalena and his daughter Rosina, who married Ferdinand Pöll in 1891, inherited the building. In 1911, the building was sold to the Landeshypothekenanstalt until it was bought two years later by Katharina Nagele. The property belonged to the Nagele family until 1967, when the innkeeper Jakob Lackner, after whom the building is named, acquired ownership.

THINGS TO KNOW & CURIOSITIES

The Berggericht as a criminal court

At the time of the witch hunts, which had also spread to Tyrol in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Berggericht not only played a role in the usual judicial procedures but was the court where numerous alleged witches and wizards, along with common criminals, were summoned, tried, and sentenced, and even executed by the local executioner.

Two executioners were employed in Tyrol since 1497, with respective official residences in Meran in South Tyrol, and in Hall (North Tyrol), to whose administrative district Kitzbühel belonged. As was the case in many other jurisdictions, and on the instructions of the court, the corpses of those executed in Tyrol remained hanging on the gallows for years as a deterrent or remained harnessed to the wheel. The gallows were a clear symbol of authority and the form of justice they exercised. While the authorities increasingly turned the executions into a demonstration of their power and no longer wanted the people to participate, the people in turn turned the punitive ceremonies and executions into popular festivals at which they not only witnessed the punishment of a criminal but also participated in a sacrificial offering to purge society. Those executed were regularly buried in unconsecrated ground, often in the immediate vicinity of the gallows. The explicit order to bury the executed or the ashes of the executed at the gallows or at a pre-determined place is related to the supposedly powerful magical effect associated with their remains.

These execution sites, however, became superfluous in 1787, when the death penalty for ordinary criminal jurisdiction was abolished in Austria with the introduction of the Josephinisches Strafgesetz, a penal code issued by Joseph II (1741-1790) for the hereditary lands of the Habsburgs. In 1795, after the death of Joseph II, the death penalty was however reintroduced. Most of the old execution sites, including Kitzbühel, were not used again. From this time on, executions were only carried out at the courts in Innsbruck and Bolzano.

ARCHITECTURE

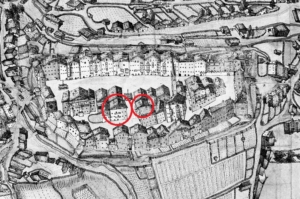

As repeatedly depicted by the architect, painter and Kitzbühel resident Alfons Walde (1891-1958) in his works of art created from the beginning until the middle of the 20th century, the rooftops of the Tyrolean city are particularly eye-catching. Seen from above, the characteristic arch of the old town houses appears as a closed roof landscape. This was also captured in photography and art during the 1900s when there was renewed interest in the alpine area. Walde impressively captured its charm after Andreas Faistenberger (1649-1735) had captured Kitzbühel, in the traditional Renaissance bird’s eye view, three centuries earlier.

The 14th century High Gothic Church of St. Catherine, with its high, pointed tower, is already particularly prominent in these aerial photographs as the core of the medieval town centre. However, the former Berggericht, in the immediate vicinity of the church, has also always been a striking eye-catcher.

Berggericht

The massive, free-standing, four-storey building with its saddle roof and rectangular structure, is the highest secular building in Kitzbühel’s city centre. The four corners of the building are characterised by the bevelled chamfers that reach up to the window height of the ground floor. The façades are unstructured and characterised by an irregular arrangement of axes. On the gable side, facing the rear of the town, the two far left axes jut out, forming a corner. A wide bay window, extending over the second and third upper floors, is incorporated into this corner. There are three window axes on the eastern side. A square, stone framed original window from the 16th century is still preserved in the central axis on the ground floor. There is a high, bevelled arched portal in the centre of the western side.

The interior is accessed via a vestibule, which is characterised in particular by its impressive late-Gothic barrel vault, decorated with ridges and lunettes. The barrel vault has largely been preserved in its original state and adorns almost the entire ceiling. The four upper floors are accessible via the vaulted stairway on the right. The interior has other original Gothic vaults on the first and second floors. Conversions, especially on the upper floors, were carried out in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Gothic pointed arch windows on the ground floor are a further special feature, making the vestibule particularly impressive and attractive.

When the building, in its present state, is compared with architectural drawings and plans from around 1620, the basic layout and number of storeys correspond. However, the gable was still made of wood at that time. In the second axis from the right, the front had a three-storey, three-sided polygonal bay window with a tented roof and cornices separating the storeys. The arched portal was situated in the centre. The fourth axis from the left carried a wide bay window resting on consoles on the second floor. The two left axes, which are closer together, clearly jut out. Only three windows can be seen on the southern side. The rear view of the building is partially obscured by the tower of St. Catherine’s Church. Here, a window axis is visible to the left of the tower; to the right of it, two axes that are closer together can be seen. The last structural changes, including the erection of various light walls, took place in around 1963 and resulted in the two upper floors no longer having any original building substance in their interior.

Lacknerhaus

The Lacknerhaus, formerly known as the “Lintnerhausstöckl”, was created due to the historical separation of the Vorderstadt and the Hinterstadt. Architecturally it is a twin building, an extension of the original building in the Vorderstadt which was built at the beginning of the 17th century. The windows in the inner courtyard still bear witness to this unusual architectural history. The four-storey corner building with its russet façade is characterised by its dramatic figuration, which is so typical of the local angular and massive architecture of secular buildings. With a rectangular floor plan and a saddle roof, the simple building is characterised by its front with six window axes. The third opening from the left is a round arched portal. Inside there are imposing barrel vaults that lend the rooms a certain generosity.

STRUCTURAL CONDITION AT TIME OF ACQUISITION

Berggericht

At the time of the acquisition by The European Heritage Project in 2012, the Berggericht was in an extremely neglected state since no maintenance work has been carried out for a decade. The vacancy caused extensive frost damage to the masonry, load-bearing wooden structures, and pipes. In addition, substantial building transgressions occurred due to renovation work in 1963. The entire building structure had suffered considerable alteration, for example through numerous room partitions with lightweight walls, enlarged window openings, and the installation of plastic windows. Unfortunately, the third and fourth storeys were particularly affected where there was no longer any original building fabric that could have been renovated.

Lacknerhaus

When The European Heritage Project acquired the building in 2013, the entire structure was in a ruinous state as the building had been entirely unoccupied for several decades. In addition, the previous owner had been unable to carry out any restoration or renovation work due to a lack of financial resources.

The external appearance seemed to indicated demolition, but the interior of the building presented a significantly worse picture. Due to the dilapidated condition – broken or missing windows, decrepit or partially missing pipes, a roof truss at risk of collapsing, water and frost damage, severe pest infestation – the question arose whether this building could be renovated at all.

RESTORATION AND CONSERVATION MEASURES

Berggericht

The vacant building was subject to decay until it was acquired by The European Heritage Project in 2012. When the authorisation for the restoration and conservation measures was granted in the following year, the renovation of the old building commenced.

Particular attention was paid to the downsizing and reduction of the door and window openings, which were altered during renovations in the 1960s, to allow the characteristic Kitzbühel wall construction to come to the fore again. Unsuitable, retrofitted plastic windows were replaced by historically accurate reproductions. The door frames were restored true to the original. Replicas of the wind shutters, based on the original model from around 1620, were commissioned. To reconstruct the original historical condition of the rooms on the ground floor, as well as on the first and second floors, the subsequently built-in lightweight walls were dismantled and removed.

This was unfortunately no longer possible on the two upper storeys, including the roof structure, as there was no original building fabric left. However, the modern tin roof was replaced by a reconstructed wooden shingle roof, as it was originally in the 16th century. During the restoration of the damaged and heavily soiled façade, the traditional Lüftlmalerei (mural art native to towns in southern Germany and Austria) was restored, and the trompe l’oeil which once adorned the building was reconstructed in the Mannerist style.

The core component of the restoration measures was the preservation of the Gothic reticulated vaults on the ground floor and the first two floors. Isolated fractures in the fragile construction were repaired with filler material, and the cracked and split plaster as well as the wall paint were repaired in numerous places. The existing wooden and stone slab floors were also repaired meticulously.

Since the Berggericht had been vacant and unheated between 2002 and 2011, there was considerable frost damage to the pipes and the beams of the roof truss. The resulting damage had to be repaired with great effort and all pipes re-laid. In addition, the foundations were extremely damp and therefore had to be dried and re-insulated entirely. In this context, the decision was taken to construct a retention tank to separate rainwater and waste water in order not only to comply with the latest environmental protection guidelines, but also to set ground-breaking standards for the city of Kitzbühel.

Lacknerhaus

First and foremost, the neglected interiors of the Lacknerhaus had to be cleared of debris, including animal carcasses. After clearing, pest control measures followed due to the severe infestation by various vermin. Massive water damage and the resulting spreading of mould throughout all floors posed a major problem, for which reason the entire building, from the foundation to the roof truss, is being dried out and statically secured.

The rotted beams of the original roof structure, which threatened to collapse, was repaired with the help of experienced structural engineers and restorers. During the restoration and stabilisation of the late Gothic, simple barrel vault, the team drew on the valuable experience gained in renovating the Berggericht.

The decades-old power lines and water pipes, including the sanitary facilities, were in a completely dilapidated condition and were modernised according to the latest technical and energy-saving standards. An entirely new heating system was installed.

Doors and windows throughout the building were leaking and partly broken. During the restoration work all doors and window frames were insulated and fully restored or replaced.

The old exposed staircase was entirely preserved.

All renovation work was completed in 2024.

PRESENT USE & FUTURE PLANS

The The European Heritage Project has successfully completed the restoration measures on the Berggericht. Large parts of the building are again accessible to the public. The ground floor is used as retail space, and the first floor as a catering area for a top restaurant. The fine-dining restaurant “Berggericht” established there has since received several awards, including 4 toques from the renowned Gault-Milau guide and ranks among the top three restaurants in Tyrol.

The Lackner House has also been revitalized. The first floor now houses one of the most popular bistros in the city, as well as a long-established jewelry store. The rooms on the upper floors are used for residential purposes.

In cooperation with the city, it was also possible to renovate the area surrounding the buildings. The European Heritage Project Project has made its own contribution to the redesign of Kitzbühel’s pedestrian zone and actively participated in the work. Weekly markets and other events now take place around the houses, which have led to a significant revitalization of this once neglected part of Kitzbühel’s old town.

Videobeiträge:

Das Restaurant Berggericht öffnet seine Tore in der Kitzbühler Altstadt. Haben Sie Teil an den Feierlichkeiten und machen Sie sich einen ersten Eindruck vom Fine Dining Restaurant im Herzen der Gamsstadt!

Marco Gatterer ist der Küchenchef des Restaurants Berggericht in Kitzbühel. In diesem Interview gibt er einen Einblick in seinen bisherigen Werdegang und erklärt, auf welchen Säulen seine Küchenphilosophie beruht.

Im Restaurant Berggericht in Kitzbühel sind Heinz Hanner und Marco Gatterer für die Umsetzung des Konzepts “Zurück in die Zukunft – Gerichte mit Geschichte” verantwortlich. Hier gewähren Sie einen Einblick hinter die Kulissen des Fine Dining Restaurants, das Peter Löw im Rahmen seines European Heritage Projects in der Altstadt betreibt.

Heinz Hanner blickt auf mehr als 40 Jahre Gastronomieerfahrung zurück. In der Kitzbühler Altstadt betreibt er nun in Zusammenarbeit mit dem European Heritage Project von Peter Löw das Fine Dining Restaurant Berggericht.