The venerable convent of San Martino a Sezzate is the flagship of the culturally protected Cintoia Valley. From the Roman emperors to the Florentine patrician Bardi family, European history was written here.

Together with the famous three castles (i tre castelli) of Castello di Mugnana, Castello di Cintoia, and Castello di Sezzate, the convent of San Martino, with its medieval church, forms the visible landmark of the so-called “enchanted” Cintoia valley, la valle incantata.

Strategically situated between Florence and Sienna, it was a bone of contention between imperial and papal loyalists for centuries. The convent is situated a on the Roman Via Cassia which later became part of the Via Francigena, an ancient road and one of Medieval Europe’s most important pilgrimage routes leading from Rome to Canterbury.

During the 17th century, San Martino a Sezzate experienced its most notable patronage under the Florentine patrician family Bardi, who emerged as Europe’s most influential bankers, financing amongst others the discovery of the Americas and helped the Medici rise to power by way of marriage.

San Martino a Sezzate has always been closely linked to the neighbouring Castello di Sezzate as it was the spiritual centre of the nearby castle. While the name Sezzate refers to a 7th century Lombard settlement, the convent of San Martino was first documented in the 12th century.

Today, the convent as well as the neighbouring village of Sezzate, with its large agricultural lands, belong to The European Heritage Project. As part of the Chianti region, the famous Chianti Classico is grown here in addition to olives. In the consecrated church of the convent, the Holy Mass is celebrated today as it was then.

MORE | LESS

Located on the elevations of the Poggio La Sughera, the property overlooks the entire Cintoia Valley, but also offers panoramic views of the Tuscan hills all the way to Monte Amiata. The old Via Cassia pilgrimage route meanders directly along the border of the property. Archeological findings on the property indicate that earlier Roman buildings already stood at this important strategic position.

When The European Heritage Project in a step-by-step process acquired the San Martino estate, large parts of the village of Sezzate with almost 30 hectares of land including olive groves and vineyards, as well as an adjacent farm, it was in an undeniably neglected condition. The heritage building stock had suffered severely from various unprofessional alterations. Some buildings were on the verge of collapse.

Sezzate, about 15 kilometres south of Florence, is located in the historic centre of Tuscany, in an area that was the cradle of the Etruscan civilization and later of advanced Italian culture which spread from Tuscany throughout Europe during the Renaissance. The estate, together with its ancient olive trees, the autochthonous Chianti Classico grapevines, and the consecrated sacral buildings, represents European cultural identity on a small scale and embodies the birth of the humanist ideal.

The European Heritage Project is committed to the protection of such historical rarities, including the preservation of the archetypal Tuscan landscape, and the regional wine and food culture.

PURCHASE SITUATION

After having been under the administration of the Archdiocese of Florence for centuries, the church and convent complex of San Martino were sold to an Australian-Italian couple (the wife being Australian) in 1985. The 17th century patrician villa, situated at the foot of the hill a little below the convent, belonged to an Italian family operating an agriturismo.

After the tragic death of the Italian husband of the couple owning the convent complex, The European Heritage Project acquired the higher lying estate in 2006. The widow evidently did not want to stay with her Italian mother-in-law, but rather return to Australia.

The purchase of the patrician villa including the farmland followed in 2014, when the owner of the agriturismo decided to retire after the sudden death of her husband, and offered the heritage building to The European Heritage Project. Further agricultural land and buildings as well as large parts of the abandoned village of Sezzate were acquired in the years to follow.

Since the layout of the roads had changed considerably over the past 500 years, and the Roman road had long since ceased to be used as a transport route, local residents were no longer able to rely on farming. The rural population had migrated to the towns on the lower lying plains.

An important ensemble of Tuscan history has been reunited. By acquiring the various plots, everyday life at San Martino is once again defined by the wine industry, olive cultivation, as well as sacred contemplation.

REAL ESTATE FACTS & FIGURES

The convent of San Martino a Sezzate belongs to the municipality of Greve in Chianti. It is situated approximately 15 kilometres south of Florence, and about 45 kilometres north of Siena, on the edge of the Cintoia Valley. The entire valley has been declared a conservation area.

The estate consists of the convent buildings including the convent church, as well as a 17th century patrician villa with adjoining farm buildings, and several village buildings which were historically used partly for residential purposes but mostly for agricultural purposes. A proprietary cemetery is located between the convent and the patrician house, which has not been used for more than a century.

The living areas add up to more than 2.000 m². The total area of the property exceeds 30 hectares, of which almost 23 hectares are used for olive production (around 3.500 olive trees), and 4 hectares are used for the cultivation of Sangiovese grapes. The vineyard is certified to produce the famous Chianti Classico. The olive oil produced has meanwhile won several international awards.

HISTORY

Up to the 7th Century: Etruscans, Romans and Lombards: The Early Settlement of Sezzate

In the first millennium before Christ, an Etruscan settlement known as “Munius” was located in the immediate vicinity of the convent. While the Etruscans called themselves Rasenna, the Romans referred to them as the Etruscans, the Etruscī or the Tuscī. This Roman name became the origin of the word “Tusculum”, the predecessor of today’s name Tuscany.

In the subsequent Roman period, the area took on an important military function, since the military road Via Cassia, which led north from Rome, crossed the ridge to the west, to approach Valdarno, the Arno valley. Remnants of the old Roman road border the property to the east and are still visible today.

During the 5th century, the Roman Via Cassia became a part of the Via Francigena, a significant transportation road as well as a pilgrimage route running from the cathedral city of Canterbury, across the English Channel, through France and Switzerland, to Rome. The Italians named it Via Francigena, “the road of the Franks”, and it still holds its significance as one of Europe’s longest and most important pilgrimage routes up until today.

12th – 14th Century: A sought-after territory — Sezzate as the core area of political dispute

Although the name Sezzate refers to a Langobard settlement from the 7th century, it was not until the 12th century that it was documented. At that time the church belonged to the nearby Castello di Sezzate, a typical medieval fortification originally surrounded by a village. The landlords were the Florentine Alamanni family, who belonged to the loyal faction of the Ghibellines, the imperial party in the conflict between the Holy Roman Empire and the Pope, who was supported by the Guelphs. In 1198 the “Lega Toscana”, an alliance between the city of Florence and various towns and villages in the Chianti region, was proclaimed here. Until the second half of the 14th century, the border of the Holy Roman Empire, i.e. the southern border of the region Tuscia, ran about 100 kilometres south of Sezzate. It was there that one of the most violent clashes between papal and imperial troops would later take place.

The entire area of Sezzate was largely economically independent after the Alamanni had built several grain mills in the Cintoia Valley during their rule in the 12th and 13th centuries. Nevertheless, the crops produced merely guaranteed self-subsistence.

In the 13th century San Martino was transferred to the family of the Conti Guidi, who as imperial governors became increasingly involved in the fighting between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. In 1249, renegade Florence was conquered by imperial troops and the papal Guelphs were forced to leave the city. Yet, the victory was short-lived. It was not until the Battle of Montaperti in 1260 between Florence and Siena that the Guelph troops were defeated. In the course of these bloody conflicts, Castello di Sezzate suffered severe damage, while the convent of San Martino was largely spared.

As one of the most prominent and decisive battles in Renaissance Tuscany, the Battle of Montaperti would later be immortalised in the Inferno’s “Canto 32”, the first part of Dante Alighieri’s (1265-1321) epic narrative poem Divina Commedia (The Divine Comedy), which was completed in 1320.

By the end of the 13th century, the Guelphs once again prevailed in Florence, and the aristocratic Ghibellines only asserted themselves in the surrounding rural areas.

15th – 18th Century

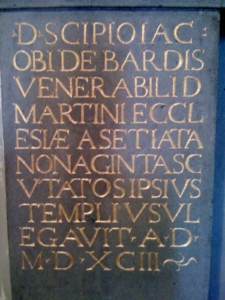

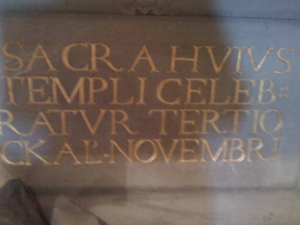

In the 15th century, San Martino fell to the famous Florentine Bardi family, who expanded and redesigned the church under their patronage in 1600. Lateral to the main altar, inscriptions still commemorate the donations of Scipione Jacopo di Bardi.

The inscription to the left reads as follows:

-

SCIPIO IAC.

OBI DE BARDIS

VENERABILI. D.

MARTINI ECCL.

ESIAE A SETIATA

NONACINTA. SC

VTATOS IPSIVS

TEMPLIVSVL

-

AVIT. A.D.

MCXCIII

“Master Scipio Jacobus di Bardi, patron to the venerable church of Saint Martin in Setiata (Sezzate) donated 90 ducats to be used for his church, AD 1593”

The inscription to the right states:

-

IONBAT

ANICH. HVIVS

ECCLESIAE R.

HOC ALTARE

PEANE DIRVTVM

AC VETVST

ATE CONSUMPV

PHUM D. SCIP

PECUNIIS RE

STAVRANDVM

CURAVIT

A.D. MDCV

„John Baptist Anchini, patron of this church, has enabled the reconstruction of the almost collapsed altar, worn out by time. The altar was reconstructed with the money of Signore Scipio. AD 1605“

The significance of the rather small church of San Martino during these times should however not be underestimated. The old Roman road was still the most important connection between Florence and Siena, as the connecting roads that are common in the valley today had not yet been developed at that time or were not used for tactical reasons. One could not but pass San Martino. Ancient topographical engravings show that, until the end of the 16th century, the small church was one of only five churches outside the cities of Florence and Siena.

Sezzate slowly gained in importance when Cosimo III de’ Medici (1642-1723), Grand Duke of Tuscany, issued an edict in 1716 officially recognising the boundaries of the Chianti district and delimiting the wine region. This document served as the first legal document in the world to define a wine-growing region.

Although wine has been produced in the Chianti area ever since the 13th century, early sources describing the Chianti wines as originally exclusively white, it was this particular edict that ultimately led to a renewed opportunity for the entire region to flourish by cultivating predominantly Sangiovese grapes, and turning them into what is now protected under the name Chianti Classico.

THINGS TO KNOW & KURIOSITIES

The Ruling Families of Sezzate

Sezzate was a politically strategic point of contention between the Guelphs, supporting the Pope, and the Ghibellines, supporting the Holy Roman Emperor, throughout the course of many centuries. In this conflict the Republic of Florence, which was ruled by papal Guelphs, tried to continuously expand their territory, while Ghibelline cities, most prominently Sienna, tried to undermine their efforts.

Yet, playing a decisive role in promoting and defending either papal or imperial interests as well as shaping Sezzate over the course of history would be the highly influential patrician families of Florence and Sienna.

In the 12th and 13th centuries, Sezzate was under the sphere of influence of the Alamanni. They were replaced by the Guidi in the late 13th century. And finally, in the 15th century, Sezzate fell to the Bardi.

Alamanni

The ancient noble Florentine family Alamanni was, as their name suggests, a family of Germanic origin. Their descent was first reported in 1478 in a short poem on the glories of Florence by Ugolino Verino (Ugolino di Vieri) (1438-1516), which reads:

“Nobile e antica fu la schiatta deli Alamanni. Gente venuta da lontano, originata da sangue germanico.”

“Noble and ancient was the lineage of the Alamanni. People from afar, originating from Germanic blood.”

Owners of various castles during the Middle Ages, the Alamanni moved to Florence in the early 14th century, establishing themselves in Oltrarno, a quarter of Florence, south of the river Arno. Already members of the nobility and a prominent and economically successful family, the Alamanni dedicated themselves to mercantile activities that helped the city of Florence in accumulating wealth in a brief period of time, from 1336 to 1340. The city chronicler and diplomat Giovanni Villani (1280-1343) described the family as one of the most important in Florence. Their company, led by the head of the family Salvestro Alamanni, traded wool and other products with other Italian and foreign states. Their immediate success made them both bankers and Lombards. Despite not being impressed by the rapid rise of the Medici family, the Alamanni strategically practiced a certain form of political neutrality. This impartiality gave them access to important positions, such as ambassador (Gonfaloniere di Giustizia), the most prestigious post in the government of the Republic of Florence. Piero Alamanni (1435-1519), for example, became the Florentine ambassador to Milan.

Yet, his son Luigi Alamanni (1495-1556), statesman, famous humanist, and prolific and versatile poet, demonstrated his hostility towards the Medici more openly. Luigi participated in an unsuccessful conspiracy against Giulio de’ Medici (1478-1534), who was to become Pope Clement VII in 1523. The conspiracy was concocted during secret gatherings in the garden Orti Oricellari, in which political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) was also involved. After the failed coup, Luigi Alamanni fled to France. He initially retreated to Lyon and then moved on to Paris, where he found hospitality and honours at the court of King Francis I (1494-1547), the king of France from 1515 until 1547, and later at the court of Henry II (1519-1559), the second son of Francis I and the king of France from 1547 until 1559. He furthermore stood under the personal protection of Catherine de’ Medici (1519-1589), the wife of King Henry II and the mother of King Francis II. After Luigi’s flight, the family property in Florence, along with their entire possessions, was confiscated. Luigi’s sons became successful in Luigi’s new home country of France. Giovan Battista Alamanni (1519-1582) became the distributor of alms to Catharine de’ Medici, and later the private councillor to King Francis I. In 1555 he became bishop of Bazas and in 1558 bishop of Mâcon. Niccolò Alamanni became commander of the French army, fighting alongside Piero Strozzi (1510-1558) in the defence of the Ghibellin city of Siena against Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519-1574), Grand Duke of Tuscany. Part of the family later settled in Naples and the region of Calabria, where they erected two palaces in the municipalities of Tiriolo and Catanzaro, thereby establishing the branch of the Alamanni di Napoli in the 18th century.

Guidi

The Guidi were an important and highly influential medieval Italian noble family that originated in the historic region of Romagna, today’s Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna, and were first documented in the 10th century. According to some medieval historians, the family descended from a certain Teudelgrimo, or Tegrimo, who was believed to have participated in the Italian campaign alongside Otto I, traditionally known as Otto the Great, (912-973) in September 951. According to this theory, he was then enfeoffed with the Castle of Modigliana by King Otto, as a token of gratitude. Documented sources, however, attest the existence of Tegrimo Guidi (900-943) earlier, mentioning him as count palatine of Tuscany, based in Pistoia. By marrying Ingeldrada, the daughter of Duke Martino of Ravenna in 923, Tegrimo became the Count of Modigliana. Ingeldrada and Tegrimo had two children, Ranieri and Guido.

By the mid-12th century the Guidi dominated the Florentine contado, or district, with properties east of Florence and in Tuscan Romagna, the contadi of Bologna, Faenza, Forlì, and Ravenna. They were most influential in the hilly Casentino country of the Upper Arno and Mugello, in the provinces of Arezzo and Florence. The noble family’s seat of power was Castello di Poppi (also known as Castello dei Conti Guidi), a medieval castle in Poppi, in the Province of Arezzo from 1190 until 1440, when the Conti Guidi, who formed an alliance with Milan at that time, were defeated in the Battle of Anghiari against the Italian League and the Republic of Florence.

During the 13th century the Guidi had however already lost many of their territories to expanding communes. In addition, they were involved in conflicts between different cities, as well as between Guelphs and Ghibellines. They were further weakened by being divided into several, sometimes opposing branches within the family, that were either loyal to the pope or to the emperor. The Casentino branch of the counts of Poppi were the last ones to preserve their independence until 1440.

Bardi

The Bardis were an influential Florentine patrician family. They gained influence through the establishment of the powerful banking company Compagnia Dei Bardi in 1250. In the 14th century, the Bardis lent King Edward III of England (1312-1377) 900,000 fiorino d’oro, or gold florins. King Edward III was unable to repay this debt, along with 600,000 gold florins borrowed from another Florentine family, the Peruzzi, one of the leading banking families of the city of Florence. This led to bankruptcy and the collapse of both family banks. During the 15th century the Bardi family continued to operate in various European centres, playing a prominent role in financing some of the early voyages in the discovery of the Americas, including those by seafarers and explorers such as Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) in 1492, and John Cabot (1450-1498) in 1497.

The aristocratic history of the Bardi family has been documented since the year 1164, when Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (1122-1190) relinquished the county of Vernio, nowadays belonging to the Province of Prato in northern Tuscany, to Count Alberto Bardi along with “the right to confer the noble title on his descendants.“ Countess Margherita, the last of Count Alberto Bardi’s line, sold Vernio to her son-in-law, Piero de’ Bardi. The property included nine communes and a castle located 22 miles outside Florence in the area bordering the historic region of Mugello. During the 14th century the family became so powerful that they were considered a threat by the Florentine government. They were eventually forced to sell their castle to the Republic of Florence, as “fortified castles near the city were regarded as a danger to the republic.”

By 1290, the Bardi family and the Peruzzi family had established branches in England and were considered the main European bankers by the end of the 14th century. The Bardi and Peruzzi families accumulated tremendous wealth by offering diverse financial services. They facilitated trade by providing the merchants with bills of exchange, similar to today’s checks. One debtor could pay in money in one town, which could then be paid out in another town to a creditor just by presenting the bill. The Bardi family had established thirteen different bank branches located in Barcelona, Seville, Majorca, Paris, Avignon, Nice, Marseilles, London, Bruges, Constantinople, Rhodes, Cyprus and Jerusalem. The fact that some of Europe’s most powerful rulers were indebted to the Bardi family ultimately led to the banking family becoming the subject of hostility.

Despite the near bankruptcy of the bank, the Bardi family ranked among Italy’s most successful merchants and continued to benefit from their noble status. Many family members occupied important positions, and served as crusaders, knights and even ambassadors to the Pope in Rome. The marriage in 1415 of Contessina de’ Bardi (1390-1473) to Cosimo di Giovanni de’ Medici (1389-1464), the first member of the Medici family to rule Florence, was a key factor in establishing the House of Medici as the most powerful political dynasty in Florence. Cosimo rewarded the Bardi family for their support, restoring their political rights upon his ascent in 1434, and in 1444 he even exempted them from paying certain taxes.

Besides banking, the Bardi family were “great patrons of the friars.” The Franciscan bishop Louis of Toulouse (1274-1297), who was canonised in 1317, for instance, was very close to the Bardis. After his death and sanctification, they purchased a chapel in the Franciscan church of Santa Croce, to the right of the altar, and built a new, larger chapel and dedicated it to Louis of Toulouse.

The Bardis were also renowned patrons of the arts. Their most famous legacy consists of two important paintings, both named the Bardi Altarpiece. The first Pala di Bardi was painted in 1484 by Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) and depicts the Madonna and Child enthroned between St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist. The second Pala di Bardi from circa 1521 is a work by Italian Mannerist painter Parmigianino (1503-1540) which is housed in the church of Santa Maria at Bardi, Emilia-Romagna, Italy, and portrays the mystical marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria.

The Bardi family also refurbished the convent church of San Martino a Sezzate.

ARCHITECTURE

Chiesa di San Martino

The medieval church of San Martino is characterised by a simple, single-nave construction that exudes tranquility and comfort. The sacristy located behind the actual altar and is connected to the nave by a curved opening.

The church has been converted on several occasions during its history.

The side altars were originally decorated by two paintings from the era under the patronage of the Bardi family. Both paintings are now part of the exhibition of the Museo di San Francesco in Greve in Chianti: the renaissance “Madonna and Child between St. Anthony Abbas and St. Lucy”, a Florentine artwork from the first decades of the 16th century, and the baroque painting „Presentazione di Gesú al Tempio“,The Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, which originally adorned the southern part of the altar. The second painting is attributed to the Florentine school of the early 17th century, and was donated by Bardi’s nephew Giovan Battista Anchini. Several other church objects were also removed over time. Particularly noteworthy is a valuable 17th century chasuble embroidered with the coats of arms of the Bardi and Strozzi families. The liturgical vestment is now displayed at the Museo di Arte Sacra in Greve in Chianti.

The orientation of the church is towards the east in accordance with historic religious custom. An oversized cross, with a Gothic torso of Christ from the late 13th century, hangs on the eastern altar wall. The sentimental posture of the head of Christ is impressively underlined by the ornamental painting covering the entire figure. Here the art-historical transition from the triumphant to the suffering Christ becomes apparent. Directly in front of it is the 17th century mannerist high altar which serves as a divider for the church interior. It features a typical Florentine gold colour on a lapis lazuli-blue base as well as numerous tin-glazed grotesques and figurative representations. Both were created around 1500 and form the right and left wings of the altar triptych. Two gothic figures, one the Old Testament King Solomon, and the other Saint Martin, Bishop of Tours, the patron saint of the convent, are depicted on an embossed gold background. The icons frame the almost surrealistic depiction of the Resurrection of Christ. This central altar piece from the early 16th century is no longer equipped with the typical gold base and marks an important shift in sacral art. It is characterised by its three-dimensional sfumato, a painting technique for softening the transition between colours, which was a signature feature of the Dutch and Flemish Renaissance and became widely popular in the Florentine area. To the left and right of the altar are two passageways reminiscent of Orthodox church construction.

Next to the 14th century gothic stone Madonna by the northern side of the altar, is a 17th century painting depicting the Virgin Mary with Saint Dominic and other supporting figures. It faces a representation of Saint Martin as a „Cavaliere“, a horseman, on the opposite side. This 15th century painting, attributed to Mariotto Albertinelli (1474-1515), is remarkable for its knightly representation of Saint Martin as a cavalier on horseback. This type of representation was particularly popular in the warlike times of the late Middle Ages, meant to glorify in an idealizing way the role model function of the warrior as the executor of God’s will.

The remaining walls of the church are decorated with preserved fragments of several frescoes depicting scenes from the life of Saint Martin.

The church treasury from the 12th to the 15th century, consisting of a Romanesque goblet, a Gothic monstrance and a patten, reflects the transcendent way of life which found its spiritual centre in the church of San Martino.

Former Convent

The former convent and the convent church are grouped around a closed inner courtyard. The convent comprises of three wings in which the dormitory, refectory, and study and prayer rooms were located. The masonry displays the levels of significance within the complex. Whereas the nave was built from carefully worked stone blocks, other sections were built from natural stone. Various parts of the building date from different centuries.

The two-storey Romanesque estate, the oldest parts of which date from the 11th century, is located above an olive grove which is separated by a low natural stone wall facing the road. The wall is separated by two columns that form a portal leading to the entrance hall of the church, thus underlining the historical significance of the sacral buildings. The basement of the building is a cellar hewn into the rock, with a constant temperature of 14 degrees. It was once used as a larder and wine cellar. With the church to the north-west, the monastery forms a four-wing structure.

Several larger rooms and a spacious kitchen are located on slightly offset levels on the ground floor, as this area of the convent was originally used for work purposes and receiving guests. On the second floor there are several rooms, probably formerly bedrooms and work rooms.

Despite its multi-storey construction, the architecture is modelled on a classic Roman atrium house with simple trussed rafters. The open wooden skeletal beams of the roof, visible in the ceilings, give the interior its own distinct character.

The true beauty of the building, however, reveals itself in the atrium, structured in a similar way to that in larger monasteries and abbeys. A simple stone bench extends along the entire length of the wall towards the church side. The opposite side contrasts strongly to the otherwise simple and modest natural stone architecture. It is the gem of the forum and is characterised by a Roman arched arcade, supported by four pillars decorated with Renaissance frescoes. Above the arcade there is an imposing gallery. In the centre of the courtyard there is a brick cistern covered with a turret, which leads to a spring located about 300 meters above San Martino a Sezzate. A large 17th century marble fountain is situated at the western wall. The ochre-coloured marble dominates the appearance of the inner courtyard, while accentuating the pale blue and russet elements of the arcade.

The Patrician Villa

The 17th century building, a so-called casa colonica, built by the Bardi family, is much simpler in its form than San Martino. It is located on a promontory at the edge of the Cintoia valley with an expansive view of the sloping landscape and the church of San Donato.

The free-standing, almost square structure is situated on a slope, has three levels, whereby the bottom level houses the wine cellar and the historic kitchen. The ceilings on the first level, which is also the ground level on the northern side, are plastered barrel vaults, one of which is still painted with an original 17th century fresco. The third level has a south-facing loggia, connecting the central interior hall with the outside world, overlooking the olive groves and vineyards. The façade, with its decorative gray pietra serena window reveals and portal frames with the massive, iron-studded wooden gates, lends the building a certain self-confidence and dominance.

STRUCTURAL CONDITION AT TIME OF ACQUISITION

When The European Heritage Project acquired the convent buildings of San Martino a Sezzate in 2006, the entire estate as well as the old neglected olive groves were in a ruinous condition. The campanile, which was threatening to collapse, was saved at the very last minute before damaging the nave of the church.

RESTORATION AND CONSERVATION MEASUREMENTS

Initially, a detailed room book was compiled, documenting the exact condition of each room before the renovation and restoration measures according to the specifications of the monument protection authorities.

The restoration and conservation process commenced in 2007, and by 2016 these measures were completed in all essential areas.

Today the San Martino estate is what it used to be. A place of reflection and spiritual renewal, in harmony with nature.

Statics

The convent buildings displayed minor static problems. Only missing stones in the load-bearing walls were replaced.

The souterrain of the patrician farmhouse posed more problems. Over the years, moisture had accumulated in the foundations and walls resulting in extensive water damage and mildew. The moisture had left the brickwork partly dilapidated and fragile. After months of drying, damaged elements were replaced. Today the cellars are dry and free of mildew.

The fenile, the secluded barn belonging to the farmhouse, was badly damaged. Both the roof and the supporting beams had collapsed but were reconstructed. Broken girders were stabilised by additional girders and steel beams to relieve the strain.

Roof and Fold

The roofs displayed numerous leaks. Large areas of roof tiles were removed, repaired and re-laid. To preserve as much of the original material as possible, only entirely destroyed or missing roof tiles were replaced.

Heating, Air Conditioning, Electrics, Water Supply System, and Sanitary Facilities

During the renovation of the flooring, under-floor heating was installed to preserve the authentic and historical appearance of the rooms. All water pipes, telephone and power lines, bathrooms and sanitary facilities were replaced and renovated according to sustainable, energy saving standards.

Restoration

Flooring

During the refurbishing process, the aim was to alter as little as possible and to retain the original floor laying materials, both indoors and outdoors. Only broken or missing natural stone slabs or unvarnished terracotta tiles were replaced with regional materials. The historical floors which had been removed were augmented by historical replicas.

Doors & Windows

The antique chestnut-wood doors and window frames were reworked and preserved to restore their original condition. In accordance with monument protection regulations, walled-up window openings were reopened to restore the original window symmetry.

Furthermore, rusty steel grilles on both windows and doors were restored or augmented as the heavily damaged lattices posed a high risk of injury.

Masonry

The masonry of San Martino was unstable in various places. The brittle mortar was particularly disturbing, but luckily the original natural stones of the late Romanesque building structure were well preserved overall. The stones had only to be removed, partially cleaned, and reinstalled for the masonry to be properly re-aligned.

The patrician villa was subdivided into numerous smaller rooms during the last fifty years, distorting the historic floor plan. Several self-contained apartments had been created due to the building having been used as an agriturismo. Numerous lightweight interior walls were removed and the building returned to its original floor plan.

The loggia on the third floor, which had been bricked up, was opened up, and the pietra serena pillars exposed again.

The remaining frescoes were professionally restored.

Conservation (arts, crafts, stucco, frescos, etc.)

During the restoration of San Martino, special attention had to be paid to the church, as it had suffered significantly from improper renovations which had altered its historic authenticity. The altar and some of the original murals had been highly distorted due to the use of incorrect colouring and materials. The careful removal of newer layers of paint during the early stages of the restoration process revealed that, in some cases, the original motifs had been altered completely. Based on the results of archaeological and art-historical findings, the flooring material, original wall paints, pigments, etc. were precisely conserved and restored. The restoration of the church proved to be a particular challenge for the restorers since various elements, from Gothic to Renaissance, Mannerism to early Baroque, had to be preserved.

Missing liturgical objects required for the celebration of the Holy Mass, were replaced by originals from the 14th to 17th century.

The Renaissance frescoes adorning the arcade in the atrium, as well as many other murals varying in style, epoch, colouring, and pigments, throughout the various rooms of the convent and the gallery on the first floor, were successfully restored

Essential restoration measures were largely completed in 2016. Only the newly acquired village houses in Sezzate were still being renovated. These were completed in 2024.

PRESENT USE & FUTURE PLANS

One aim of The European Heritage Project was to recommence agricultural activity on the San Martino estate. Today olives are grown on more than 20 hectares of land to produce the famous Tuscan olive oil. The oil has already won numerous awards.

Winemaking has resumed and the famous Chianti Classico is now grown on approximately 4 hectares.

A concept is currently being developed to reopen the patrician villa for overnight guests.

The convent area again serves as a place of tranquility, contemplation and prayer.

Videobeiträge:

Neben eigenen Weinbauflächen in Deutschland und Südafrika betreibt das European Heritage Project im Chianti Classico Gebiet in der Toskana auch eine eigene Olivenölproduktion. Löw TV war bei der Ernte und Produktion des Öls vor Ort.