As if it were a unique time capsule, Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit revives bygone eras and social changes in its walls and foundations, making two millennia visible and tangible.

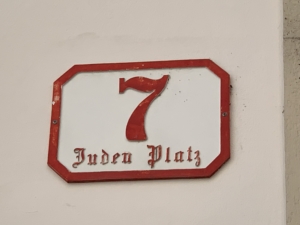

The historic townhouse at Judenplatz 7 in the first municipal district of Vienna, the property Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit, is a four-storey building located in the northwest of Vienna’s famous Judenplatz (Jewish Square) in the oldest part of the city. It is thus an essential part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the historic centre of Vienna. The building is named after an original Baroque stone statue, at the prominent corner of the building overlooking the entire square, which represents the Holy Trinity.

The building is one of the most important witnesses to Vienna’s past. The individual segments of its structure tell the entire history of Vienna. Like in a unique time capsule, Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit revives bygone eras and social changes, making two millennia of Viennese history visible and tangible.

The lively history of the building begins in 15 BC when the Romans founded the colony Vindobona. In the immediate proximity of the Praetorium, which at that time divided the Jewish Square in two, stood the buildings of the Praetorian Guard, where Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit stands today. Relics can still be found in the numerous vaulted cellars of the building. Changes took place during the early Middle Ages. From the late 13th century to the early 15th century, it became part of the Schulhof, the focal point of the medieval Viennese Judenstadt, the city’s Jewish quarter. After the so-called Geserah in 1420/2, a brutal pogrom against the entire Jewish population, the destroyed property was donated by Duke Albrecht V to the supreme trustee of Austria, Wilhelm von Puchheim, and was totally rebuilt, this time replacing the previous wooden construction with solid masonry. In 1437 the Puchheim Trinitas Chapel was donated for celebrating a perpetual mass. In 1619 a devastating fire destroyed large parts of the historic city centre of Vienna, including the chapel. A new building was soon erected, but without a chapel. Only the name remained, Trinitas, the Holy Trinity. Today only the three-storey basement rooms and the Gothic corpus with cross vaults on the ground floor bear witness to the original medieval structures.

MORE | LESS

At the time of the Turkish sieges of Vienna in the 16th and 17th centuries, tunnels were excavated under large parts of the old town. Two secret passages from this time were exposed during restoration on the initiative of The European Heritage Project. In 1796 the building was acquired by a new owner and was transformed into a late baroque townhouse before it was again modernised in 1816. The Puchheim chapel disappeared. Due to its prominent location, Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit became a sought-after location for various retail businesses serving the imperial and royal court (so called “k.-u.-k.-Hoflieferanten”).

Up to the time of its acquisition by The European Heritage Project in 2004, Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit was vacant and uninhabitable. The statics and roof were in a dilapidated condition, the entire building structure in need of an urgent general overhaul. The building left a pitiable overall impression.

After decades of neglect, Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit became the notorious eyesore of the Jewish Square. All the other buildings on the square, except for Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit, had already been renovated. It was precisely this situation that prompted The European Heritage Project to acquire this unique and venerable building and immediately implement restauration measures.

Today, the late baroque façade blends perfectly into the ensemble on the square consisting of the Misrachi-Haus which houses the Jewish museum, the old sewing guild building, the former Bohemian State Chancellery now housing the Austrian Supreme Court, the medieval Jordan house, and the Austrian Hotel Management School building where in 1783 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed his famous Great Mass in C minor, (K. 427.

A highlight was the visit of Pope Benedict XVI in 2007, who, together with the Viennese Chief Rabbi Paul Chaim Eisenberg, stood in silent devotion in front of the building Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit.

Defying the transience of time, the stone sculpture of the Holy Trinity still blesses those visiting this truly unique place.

PURCHASE SITUATION

At the time of the acquisition of the late Baroque townhouse Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit by The European Heritage Project in 2004, the listed property was in a dilapidated and desolate state. The uninhabited building, the unlet shop on the ground floor, and the dreary grey façade, represented an unsightly contrast to the other buildings on Judenplatz. The owner did not have the means to carry out any renovation. She turned to The European Heritage Project for help.

The aim of The European Heritage Project was to keep alive the long and eventful, at times traumatic history of Judenplatz, which was converted into a pedestrian zone in 2000, and to harmoniously integrate this part of Judenplatz into the overall ensemble by renovating Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit in accordance with heritage preservation requirements. According to the city, this has succeeded.

Since being redesigned, the Jewish Square, as a place of tranquillity and contemplation, has been an entity of remembrance. In 2002 the city of Vienna was awarded the special architectural prize “Dedalo Minosse International Prize” for the design of the square. Since 2006, The European Heritage Project has also made a significant contribution to actively preserving and shaping this heritage of international importance.

A highlight was the visit of Pope Benedict XVI in 2007, who, together with the Viennese Chief Rabbi Paul Chaim Eisenberg, stood in silent devotion in front of the building Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit.

REAL ESTATE FACTS & FIGURES

The late Baroque townhouse Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit, built in its current form in 1785, is located in the western part of Judenplatz in the Innere Stadt, the 1st municipal district of Vienna, which forms the historic core of Vienna. The listed building is directly adjacent to the Misrachi-Haus, which houses the Jewish Museum, and also opens up to the adjacent Drahtgasse.

The five-storey building today offers space for a shop on the ground floor, offices on the first floor, and living space on the other three floors as well as the attic. In addition, the building has spacious vaulted cellars. The living and usable areas are spread over a total of 1,300 square meters.

HISTORY

1st – 11th century: from Vindobona to Vienna

The history of the Jewish Square, which today houses the predominantly Baroque building Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit, begins when the Romans founded a legionary camp and the colony of Vindobona on this site between 15 BC and the 1st century AD.

In the immediate vicinity of the Praetorium, which at the time divided Judenplatz in two, stood the buildings of the Praetorian Guard. Relics from antiquity can still be found in the vaulted cellars of the building, which were carefully excavated during the restoration of the basement. Evidently the building at that time was well below the level of the building today. Support beams and floor fragments point to the Roman era.

On the site of today’s Viennese old town near the Danube, the Romans built a castrum, a fortified military camp, to secure the borders of the province of Pannonia, which extended as a surveillance area from Castra Regina, today’s Regensburg, to Singidunum, today’s Belgrade. The town of Vindobona in what is now the third municipal district of Vienna was connected to this. The course of the wall and the streets of the camp are still visible today in the streets of the first municipal district. The Romans remained in what is today Vienna until the 5th century. Some well-preserved remains of wall paintings and stucco fragments from the quarters of the camp commander, the legatus legionis, were discovered in the eastern part of the Jewish Square.

The castrum existed until the beginning of the 5th century when it was finally abandoned by the army. Although traces of Roman settlements also end at this time, Vindobona was probably not entirely destroyed or abandoned. A residual population continued living there until the early Middle Ages. The remaining Roman buildings were then covered up or cleared away by people stealing the stones, including Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit. Only the basement area remained.

The Berghof, a farmyard for viticulture which emerged as the core of a remaining settlement on the former Roman territory of Vindobona, became the centre of early medieval Vienna. The Berghof was located in the area of Hoher Markt, Marc-Aurel-Strasse, Sterngasse, and Judengasse, in the immediate vicinity of St. Rupert’s Church (Ruprechtskirche), the oldest church in the city still existing in its basic form, and was only 200 meters from today’s Judenplatz. It is therefore likely that this area around the Jewish Square remained inhabited. According to the sources of the poet and chronicler Jans der Enikel (ca. 1230-40- after 1302), the Berghof is said to have been under pagan rule.

12th – 15th century: From Vienna’s Jewish quarter to the bloody Geserah

Like other cities in medieval Europe, Vienna had a Jewish quarter, the relative isolation of which was by no means to be regarded as an exclusion initially. The so-called Judenstadt, the core of which was on today’s Judenplatz, known as the Schulhof until 1421, was first mentioned as Schulhof der Juden (the schoolyard of the Jews) in 1294 in its function as the centre of the medieval Jewish quarter. The Judenstadt stretched north to the Gothic church Maria am Gestade (Mary at the Shore), the west side was bordered by the Tiefer Grabe, the east side was bordered by the Tuchlauben, and the south side by the Platz Am Hof. The ghetto comprised 70 houses, arranged in such a way that their rear walls formed a closed boundary wall. These buildings were wood constructions built over the Roman foundations. The Judenstadt could be entered through four gates. The square consisted of the synagogue, the only stone building among the private and community houses and which occupied a third of the square in the west, as well as the hospital, the rabbi’s house and the Jewish school. Renowned rabbis taught and worked here, turning the city into a hub of Jewish knowledge. The Schulhof was surrounded by fifteen houses and five streets led into the square.

The rabbi Isaac ben Moses (also called Isaac Or Zarua or the Riaz) worked in Vienna from around 1260. One of his major works, known as the Or Zarua (in English “light is sown” or “the seeds of light”) is the name given to the synagogue built on Judenplatz. The area on which the building Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit stands today consisted of two wooden houses which were listed with the numbers 342A and 342 in 1421 after the abolition of the Jewish quarter. The exact function of the two buildings or who inhabited them is not documented. However, the immediate proximity to the adjacent Misrachi-Haus, today Judenplatz number 8, suggests that the buildings were community halls that belonged to the synagogue and thus most probably played a religious rather than a secular role.

With the start of the Crusades, however, anti-Jewish tendencies intensified, and the social and legal situation of the Jews, who had practically equal rights up to that point, deteriorated rapidly. Reports of alleged ritual murders of Christians, host desecration, and the poisoning of wells that caused plague incited the superstitious population against Judaism. Violent attacks increased and led to the first persecution of Jews in Austria in 1338.

At the beginning of the 15th century the situation of the Jews in Austria further deteriorated. An incisive event was the fire in the Jewish quarter which broke out in the synagogue on the Schulhof on 5 November 1406. At that time, a fire endangered the entire city. The cause of the fire remained unknown, but the Jews were held responsible. There were widespread looting and rioting against the residents of the quarter, not least because of the fire-related loss of the citizens’ valuables pledged to Jewish pawnbrokers. The prosperity and economic importance of the Jewish community were severely affected by the fire. The Jews were increasingly seen as a threat to the city.

In 1411, at the age of fourteen, Albert V (Albrecht V.)was declared to be “of age” and immediately levied draconian taxes on the Jews to cover the costs of the new court and enable the completion of the tower of the St. Stephan’s Cathedral. Due to the religiously motivated Hussite Wars (1419 – 1436), also called the Bohemian Wars, tensions escalated in the 15th century. Albert accused the Jews of collaborating with the reformatory Hussites and ordered the systematic abolishment of the Jewish communities and the expulsion of the Jews from the duchy .

The persecution of the Jews reached its climax in 1420/21 in the bloody Vienna Geserah (derived from a Jewish chronicle, the “Wiener Gesera”). On 12 March 1421, Albert V issued a decree condemning the Jews, if they did not emigrate, to death. In addition to the “general malice” of the Jews, one of the reasons given was that the Jews were guilty of host desecration. The remaining Viennese Jews, 92 men and 120 women, were executed that same day on the Gänseweide in Erdberg in what is today the third municipal district of Vienna. The possessions left behind were confiscated, the houses either sold or given away to minions. The ghetto around the Jewish Square was torn down, the synagogue demolished, and its stones used to build the old Vienna University. The Judenstadt was thus depopulated and abolished.

The buildings, which in 1421 were listed as numbers 342 and 342A and of which the foundations preceded the building Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit, were donated by Duke Albert V to the highest administrative official of Austria, Wilhelm von Puchheim. Excavations in the 1990s revealed that the present building at Judenplatz 7 directly adjoined the Or Zarua synagogue. The excavations also revealed that the remaining buildings, built on relatively small areas, were wooden constructions. These were constructed in threshold and frame construction methods and were equipped with simple clay floors, including today’s Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit. From 1423 onwards, the Schulhof is mentioned in several sources under a new name and is henceforth referred to as “Neuer Platz” or “newy placz” (new square), until its name was again and definitely changed to Judenplatz in 1437.

After the Geserah, Vienna went down in the chronicles of the Jewish community as the “City of Blood”. More than two centuries were to pass before Jews settled in the city and in other parts of Austria again.

15th and 16th centuries: catholic rule and the first Turkish siege of Vienna

After the buildings were donated to Wilhelm von Puchheim, two new adjoining stone buildings were erected on the site of today’s Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit. The foundations, which were originally listed by order of Duke Albrecht as buildings 342 and 342A, were thus preserved in their layout. The rear building, the area of which is not visible from Judenplatz or Drahtgasse today, was donated on 11 October 1437 for celebrating a perpetual mass in the Puchheim Chapel of St. Stephen’s Cathedral. Thus, a part of today’s Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit was once a church. The trinitarian dedication of the building can also be derived from this sacred building.

The noble Puchheim family not only belonged to the loyal favourites of the ruling Habsburg dynasty, but were also anxious to demonstrate their status, power and wealth with generous gifts in support of sacred architecture. Due to the relatively long distance between the Puchheim Chapel and St. Stephen’s Cathedral, it can be concluded that the chapel was intended to extend the scope of the cathedral, which was only designated as a cathedral in 1469. The Gothic ribbed vaults on the ground floor of Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit, which are still preserved today, date from the first half of the 15th century. The chapel, however, could not be preserved. With the consent of his son, the chaplain of the chapel sold the front building in 1456. Between 1456 and 1547, both buildings were once again owned by the same family.

During the renovation and restauration work by The European Heritage Project, basement rooms and accesses to two underground connecting passages were discovered and excavated. From the time of the Turkish sieges in the 16th and 17th centuries, Vienna had a network of underground corridors, cellars, and vaults. The corridors were sealed off by a concrete wall after about three meters. Since the tightening of the Vienna Building Act of 1952, many of the houses in the first municipal district of Vienna are no longer connected. According to various municipal departments, the corridors were filled in with concrete when the square was designed to ensure that the square could be driven over. There is no longer any precise topography available today for the once complex underground tunnel system of the first municipal district.

At the time of the Ottoman sieges of Vienna, there were numerous, centuries-old, robustly built cellars which were built between the Roman era and the Middle Ages. Work began in the 16th century to expand many of the cellars and connect them with new corridors for the protection and supply of Vienna.

The first Turkish siege of Vienna in 1529 was climactic in the ongoing wars between the Ottoman Empire and the Christian states of Europe which lasted between the 15th and 17th centuries. Ottoman troops surrounded the city of Vienna from 27 September to 14 October 1529. At that time, Vienna was one of the largest cities in Central Europe and the capital of the Habsburg Monarchy. Due to its location between the Alps and the Carpathians, it was of great importance to the Ottomans as the gateway to Western Europe, and they hoped to conquer the whole of Europe by taking the city. However, the city was successfully defended.

17th century: ” Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit” and the Second Turkish Siege of Vienna

After Vienna had been successfully defended against the Turks in the 16th century, military peace returned to Vienna for the time being. It would take more than 150 years before a second siege of the city was to take place. On 5 May 1619, the Puchheim chapel fell victim to a severe fire which destroyed several houses in the historic core of the Austrian capital. The fire was so devastating that the fire protection and building regulations of the city of Vienna were revised and tightened shortly thereafter. The building, however, was soon rebuilt The building was soon rebuilt, but without a chapel. As a reminder, the building was named Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit derived from the chapel. Whether the building was already decorated and protected by an icon of the Holy Trinity or a fresco is, however, not documented.

When the second wave of plague struck Europe, Vienna was not spared disease, misery, and death. The plague, which raged in the Austrian capital in 1678 and 1679, and ravaged large parts of the population, brought with it economic and cultural stagnation. Vienna had barely recovered from the scourges of the “Black Death” when the Ottomans invaded the city with the ambitious plan to conquer it once and for all. Fortunately, the Second Turkish Siege of Vienna in 1683 also represented an unsuccessful advance by the Ottoman Empire, as was the case 154 years earlier.

The tunnel warfare started by the Ottomans represented a major threat to the successful defence of Vienna. Since the Turkish army could not penetrate the city walls with their cannons since the walls were several meters thick and sometimes tripled, the miners were employed. For 61 days, Turkish soldiers dug a vast network of trenches and created an underground tunnel system in order to shatter the walls by means of explosions. The besieged responded by digging a system of tunnels of their own. Underground tunnels and cellar vaults had already existed in the Roman city of Vindobona, as well as in medieval Vienna, but it was only during the two Turkish sieges that a complex tunnel system was created to defend and protect the citizens. The following tactics were used: Firstly, cellars were built beneath the entire first municipal district. The existing cellars, mostly vaulted and built with fired bricks as is the case in the basement of Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit, were several meters below the ground and served as storage and cold storage rooms, hospitals, and assembly halls. Even chapels were built in this underground city. At the time, even the catacombs under St. Stephen’s Cathedral were connected to this system. Two tunnels went out from Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit: one in the direction of St. Stephen’s Cathedral and Hoher Markt, the other in the direction of the square Am Hof.

The Christian miners aimed at collapsing the enemy tunnel system by targeted counter-explosions. The tunnel warfare dominated the siege for a long time. The tide turned only due to the German-Polish relief forces under the military leadership of the Polish King, John III Sobieski, who unexpectedly came to Vienna’s aid. The Turkish army was defeated at Kahlenberg in 1683 and forced to flee. Vienna was saved.

18th and 19th centuries: late Baroque reconstruction

In 1713, Vienna was ravaged by the plague for the last time. After this fate had also been overcome and the last attempt of the Ottomans to conquer the city had been successfully countered, the population was to double in only 70 years and rise to just under a quarter of a million by 1783. As the population density increased, so did the economic upswing. The first manufactories were built in the Leopoldstadt. Sewerage and street cleaning developed, improving hygienic conditions. As a result, building activity was brisk and the city flourished.

Vienna was largely reconstructed in the Baroque style. It was the birth of the Vienna Gloriosa, the world city of the Baroque, which was to make Vienna one of the most important cultural centres of Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1783, for example, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) composed his Great Mass in C Minor (KV 427) in the Haus Zur Mutter Gottes (House of the Mother of God) at Judenplatz 3-4, the present seat of the vocational school for the hotel and restaurant industry. Mozart also completed his opera Così fan tutte here in the winter of 1789/1790.

At the beginning of the Baroque period, the magnificent Böhmische Hofkanzlei (Bohemian Court Chancellery) was built in 1714 at Judenplatz 11, today the seat of the Austrian Administrative Court.

Vienna’s largescale building frenzy did not bypass Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit. The building was remodelled in the late Baroque style in 1785. The two buildings formerly at Judenplatz number 7 were combined in 1813 to form Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit after the properties belonged to the same owner again from 1796.

It is documented that in the course of the history of Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit numerous purveyors to the imperial and royal courts and later also innkeepers were located on the ground floor of the building. From 1840, however, the building Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit was not economically at its best. The property was again divided up. In the 19th century, the ownership of the building was fragmented to such an extent that the proportions had to be listed in hundredths.

20th century to the present: from Lessing to the Schoah Memorial

After many changes of ownership, only one owner was registered in the 1905 land records. At the beginning of the 20th century, Judenplatz 7 had become quiet, but, decades later, Hitler’s seizure of power would not go unnoticed.

The bronze monument to Lessing standing on the Jewish Square today was created by the Austrian-British sculptor Siegfried Charoux (1896 – 1967) in honour of the German writer, philosopher, dramatist, publicist and art critic, and representative of the Enlightenment era, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729 – 1781). With his drama “Nathan the Wise” in 1779, Lessing staged one of the most important German-language educational plays in the spirit of enlightened humanism. In so doing, he already took up the basic idea of the Habsburg emperor Joseph II (1741 – 1790) before 1781. In 1781 Joseph II issued the “Patent of Toleration” which extended religious freedom to non-Catholic Christians living in the crown lands of the Habsburg Monarchy, and which brought about the end of the Counter Reformation. Lessing’s idea of tolerance, as well as that of Emperor Joseph II, was to be commemorated with the bronze statue.

The Lessing monument was a commissioned work with which Charoux’s design prevailed against 82 other sculptors in 1930. The work, cast in bronze, was completed in the next two years, and erected on the Jewish Square in 1935.

Four years later, after the National Socialists seized power in Austria in 1939, the monument was dismantled and melted down since the poet was branded “a friend of the Jews”, and his enlightened writings appealing to tolerance and humanity were a thorn in the side of the new dictatorship.

Siegfried Charoux, who had been exiled to Great Britain in 1935 for fear of political persecution and who, from then on, lived and worked only in London, was once again commissioned in the 1960s with the construction of the Lessing memorial as a sign of reparation. The second version of the bronze statue, however, was not unveiled until 1968, one year after Charoux’s death, at Morzinplatz in Vienna. In 1981, it returned to its original location, the Jewish Square.

In 1995, the well-known Holocaust survivor Simon Wiesenthal (1908-2005) suggested to the mayor of Vienna, Michael Häupl (*1949) that a memorial be erected to commemorate the 65,000 Austrian Jews murdered during the Nazi dictatorship, the location of which was to be the Jewish Square.

In search of a long-forgotten piece of Viennese and Jewish history, a large-scale archaeological excavation project began in 1996 at what is now Judenplatz. Initial investigations revealed that the synagogue they were looking for was actually located in front of the buildings at Judenplatz 7 to 10 and that the foundations were partly destroyed, but partly still in good condition. Ultimately, expectations of finding traces of foundation walls were far exceeded when the Bimah (the traditional lectern), prayer rooms, the vestibule, the foundations of the Torah shrines, and much more were discovered. Parts of the former Roman barracks were also found at a depth of about 6 meters.

The square, which was converted into a pedestrian zone in 2000, is now a central place of remembrance of Jewish Vienna. The Baroque Misrachi-Haus in the northwest corner of the square is part of the Jewish Museum, which also exhibits the remains of the synagogue destroyed in 1421. On the square itself, the Namenlose Bibliothek (Nameless Library) is a powerful reminder of the Shoah during the Second World War which claimed the lives of more than 65,000 Austrian Jews.

THINGS TO KNOW & CURIOSITIES

The Holocaust Memorial for the Austrian Jewish Victims

In the centre of the northern end of Judenplatz, the so-called Namenlose Bibliothek, made by the English artist Rachel Whiteread (*1963), stands for the Austrian Jewish victims of the Holocaust. The walls of the memorial resemble walls of books, but the spines of the books are not legible since they all are turned inwards. The memorial, although it has a symbolic entrance, is not accessible, referring to the cultural void left by the genocide. With the implementation of Simon Wiesenthal’s idea of erecting a memorial for the Austrian victims of the Shoah, it became possible to create a place of remembrance on the Jewish Square that is unique in Europe.

The memorial by Rachel Whiteread is a reinforced concrete construction with a base area of 10 x 7 meters and a height of 3.8 meters. The names of the places where Austrian Jews died during the Nazi regime are recorded on floor friezes embedded around the memorial. A separate room on the ground floor of Misrachi-Haus is dedicated to the artist herself, documenting the artistic origins of the memorial project with sketches, models, and draft designs. The preservation of the excavations of the medieval synagogue was already an integral part of the basic plans for the construction of the memorial. With the integration of these archaeological findings into a museum of its own, which was set up in the basement of Misrachi-Haus, there is now the opportunity to explore Jewish life in medieval Vienna as part of a permanent exhibition.

ARCHITECTURE

The building Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit, as it is today at Judenplatz 7, was built around 1785 in the late Baroque style. It is named after the stone sculpture representing the Holy Trinity which adorns the corner of the building. Snow-white, in keeping with Baroque sacred art, the Holy Father and Son sit on a cumulus cloud, the Holy Spirit, depicted as a silver dove of peace, at their feet. Individual ornaments decorated with gold, such as aureoles, crucifixes, and the orb, stand out from the figurines.

The façade of the listed building has decorative details which visually divide the individual storeys. On the ground floor the arched windows have original preserved shutters. The windows on the other floors of the building are simple rectangular lattice windows. Both window forms are box windows which emphasize the impressive massive masonry in a unique way. Extending over five stories, the building, which leads into Drahtgasse, is covered by a simple tiled hipped roof with inserted gabled roofs and shed dormers.

The two atriums at the core of the building provide a unique spatial structure which lends a bright and friendly appearance to the apartments and offices. In addition, the two atriums allude to the original division of the building into two separate houses and architecturally refer to the history of the townhouse.

Despite its late Baroque style, Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit captivates with its tranquillity and simplicity, accentuated by the restrained white colour scheme with contrasting decorative elements in cool shades of grey and cream. Only the early 15th century Gothic cross vault and the sculpture of the Holy Trinity add a certain playfulness to the otherwise straightforward townhouse. With the Misrachi-Haus to the left and the Namenlose Bibliothek in front, Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit blends seamlessly into the ensemble of buildings on the Jewish Square.

STRUCTURAL CONDITION AT TIME OF ACQUISITION

Given that the building Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit had been vacant for years, that neither shops nor living quarters had been utilised, and that no renovation or maintenance measures had been carried out since the 1930s, the overall condition of the late Baroque building at the time of its acquisition by The European Heritage Project was disastrous. The building stood empty for many years and was no longer habitable. In addition to the damage to the neglacted façade, which had crumbled due to weather effects and had become black from the soot of Vienna’s inner city, numerous windows had been smashed. Pigeons nested in the decayed roof. However, the state of the power lines and water pipes was particularly serious and posed a fire hazard threatening the loss of the entire building structure.

All in all, Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit was in a perilous condition in 2004 and in no way reflected the eventful history of the building.

RESTORATION AND CONSERVATION MEASUREMENTS

The European Heritage Project succeeded in rebuilding the Viennese townhouse Zur Kleinen Dreifaltigkeit after it had been severely neglected for more than 70 years. In several years of renovation work, the substance was rebuilt piece by piece. Due to sensitive monument protection requirements, however, the building on the Jewish Square is an ongoing project.

Statics

The overall stability of the building was permanently endangered by moisture rising from the basement rooms, since the original ventilation shafts had unwittingly been bricked up in previous decades. To prevent this process from advancing and to repair any damage caused, the ventilation shafts had to be extensively opened and renovated, and the entire building had to be dried out.

Roof and truss

The mostly leaking hipped roof needed a complete renovation and all roof tiles were replaced. The beams of the roof truss were severely damaged by water penetrating from the outside. As a result of the dampness, the rotten beams which were infested with mildew, had to be dried, repaired and, in some cases, completely replaced. Pest infestation and pigeons nesting in the roof had caused irreversible damage in places. During the reconstruction process of the roof and roof truss, it was decided, in cooperation with the Federal Office for Monuments and the commissioned architectural office, to extend the roof truss. For this purpose, the gable roof and smaller dormers, still used in the 19th century, were installed in the previously closed hipped roof, based on historical designs.

Solar panels were installed on the atrium side to enable more sustainable and autonomous energy consumption without harming the overall architectural appearance.

Heating, electrics and plumbing

All water pipes and power lines were removed and replaced as they were dilapidated and leaking and posed an acute fire hazard. The heating system was no longer functional and had to be completely re-installed. An energy pump and a heat exchanger with groundwater supply were installed. The building is thus energetically state-of-the-art and environmentally friendly.

All sanitary facilities were completely renewed.

Reconstruction

Floors

The interior of the listed building was also particularly affected. All the wooden floors, where still existent, were severely damaged and the entire parquet had to be replaced. When laying the new parquet, the decision was made to use a mixed parquet consisting of softwood floors with hardwood edgings based on the historical design. Underfloor heating was installed in the living areas on the upper floors in order not to distort the historical appearance of the rooms with radiators.

Stairs and elevators

The stone staircase in the stairwell has been preserved in its original state. In addition, it was important to make the townhouse barrier-free and accessible to all in the future. For this reason, an elevator was installed. The elevator was inconspicuously integrated into the overall complex via a shaft.

Doors and windows

The round-arched windows on the ground floor and the rectangular lattice windows on the upper floors were retained in their original form. Whereas the window frames could be preserved, the broken windows had to be replaced. In addition, the original wooden door frames as well as some wood panelling were fully restored without any loss of their intrinsic structure. The massive ornamentally designed cast-iron entrance gate with glass inserts leading to the offices and living areas, was also extensively restored.

Masonry

The damp basement rooms posed a major problem since there was no proper ventilation due to the ventilation shafts having been bricked up by previous owners. The massive masonry of the entire building had to be dried out before the numerous cracks in the fragile masonry could be repaired with large quantities of filling material. The plaster, which had cracked in many places inside and outside, also had to be renewed.

During the renovation and restoration of the Gothic cellar vaults, entrances to two underground tunnel systems, which had been excavated during the Turkish sieges, were discovered and carefully and painstakingly exposed.

Restorations (art & craft, stucco, frescoes etc.)

The entire façade of the building was refurbished. Not only was the crumbling plaster completely renewed, but the partially damaged and abraded Baroque panel decor and stucco strips on the windows were reconstructed in places, before the individual ornaments as well as the façade were repainted.

The originally polychrome religious image of the Holy Trinity had, in the meantime, turned snow-white due to weather effects. The Baroque statue was painstakingly restored in detail according to historical models, including the gold and silver decorative elements.

The Gothic three-part cross-ribbed vault on the ground floor, which represents the interior architectural masterpiece of the building, was statically straightened in its elements, and restored true to detail. In close cooperation with the monument protection authorities, restorers, and plasterers, the ceilings and walls in the interior areas were subsequently augmented with historically accurate late-Baroque overdoor stucco. In some areas, reconstructions had to be used, as some decorative details were no longer intact or had been completely removed.

PRESENT USE & FUTURE PLANS