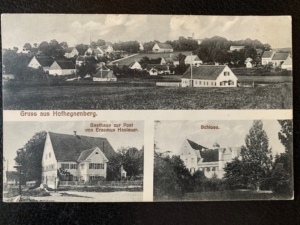

The Renaissance castle complex, which is more likely to be found in the Mediterranean area, is regionally unique and is regarded as one of the most important examples of high medieval aristocratic culture in southern Germany.

Strategically located on Roßberg hill, the highest elevation between Munich and Augsburg, Hofhegnenberg Castle is not only one of the most impressive architectural monuments in the region, but also testimony to a rich history.

The monument is one of the few castles in the Bavarian region that survived the destruction of the Swedish troops during the Thirty Years’ War. Large parts of the building complex date from the 13th and 14th centuries.

.

In the 15th century, the castle was the residence of the Dukes of Bavaria-Munich of the House of Wittelsbach, the very dynasty that would later rule as the kings of Bavaria. Designed not as a hilltop castle, but as an imperial residence, it is, besides its architectural features, absolutely unique.

The castle demonstrates the transformation from a fortress built for defensive purposes in the Middle Ages, to a prestigious Renaissance castle. This change was initiated in the mid-16th century by the legendary Knight of the Order of the Golden Spur, Georg von Hegnenberg-Dux, morganatic offspring of the Duke of Bavaria, William IV of the House of Wittelsbach.

MORE | LESS

With brittle masonry, partially collapsed roofs, and burst water pipes, the castle was in a dilapidated state that could withstand little additional load before it would collapse entirely. The defence tower on the southwest corner of the castle had already burst open and collapsed. Other outbuildings had collapsed and were only recognisable as piles of stones. The majority of the roofs were completely dilapidated, and several structural elements had broken off.

Regardless of the general degree of decay and dilapidation, a four-year renovation cycle, which was completed in 2012, rescued the castle.

The elements of the various historical styles and epochs, namely Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, and Neo-Gothic, shine in new splendour and convey an extraordinary impression of a subtle but fascinating architectural potpourri.

It was precisely this legacy that The European Heritage Project sought to preserve. The reconstruction of the 40 meter high historic keep, which collapsed after being struck by lightning in the 18th century and was subsequently torn down, posed a particular challenge. The fortified tower, which has always been considered the most important testimony to the local high-medieval aristocratic culture, is no longer a mere ghostly memory, but a reality that completes the palace complex as a unit. Today it is once again the landmark of the proud castle that can be seen from afar.

PURCHASE SITUATION

After 600 years of family ownership, gambling led to the financial ruin of the last aristocratic landlord of Hofhegnenberg. Despite his attempts to save the castle by selling off extensive tracts of land, the decline could not be averted. Even the sale of the entire family fortune accumulated over 600 years, including the sale of an astonishing 1000 hectares of land around the castle and most of the historical inventory, was ultimately not enough to pay off the debts. In the end, the tax authorities, which had already registered a compulsory security mortgage, threatened foreclosure and eviction.

At the time of the acquisition by The European Heritage Project, the deterioration caused by moisture, frost and mold was obvious. The buildings were no longer heated in winter for financial reasons, and frost damage was evident throughout. The entire north wing of the castle threatened to collapse. In one of the farm buildings, the structural damage was so advanced that renovation was not possible, and demolition remained the only option for safety reasons.

The restoration of the castle became a race against time.

REAL ESTATE FACTS & FIGURES

Hofhegnenberg Castle is situated on Roßberg hill, approximately 40 kilometres northwest of Munich and 20 kilometres southeast of Augsburg. It is located east of the village of Steindorf in the Aichach-Friedberg district, Swabia (Bavaria). The estate covers a total of around 5 hectares and consists of an enclosed park of 3.5 hectares surrounding the castle, and a further 1.5 hectares of productive land to the northeast.

Four multi-storey wings with three towers, a gateway building, and an integrated chapel are grouped around a large inner courtyard. They form the main unit with a total area of 4,000 square meters and a living area of 2,500 square metres. In addition, another free-standing building unit, the gardener’s lodge, is located on the north-eastern side of the property, as well as a large 19th century farmyard with an area of 10,000 square meters.

In the monuments register of the administrative district of Aichach-Friedberg, the estate is described as follows:

“Castle, 12th to 19th century complex grouped around a courtyard, essentially 16th century; eaves-side entrance wing with hipped roof and dormers, gateway entrance, baroque, two adjoining gable buildings, medieval keep, castle chapel, mid-16th century and expanded in 1726; with facilities; adjoining park to the south. “

HISTORY

13th and 14th Century: Building a Bastion

It is assumed that the construction of the original high-medieval fortress began around the dawn of the 14th century, when the ministerial family Hegnenberg left their original motte-and-bailey castle in today’s municipal district of Althegnenberg, only five kilometres from Hofhegnenberg. The relatives of the same name, most probably originating in Upper Swabia, were first officially documented at the end of the 12th century, when Engelschalk and Hermann von Hegnenberg were listed as vassals to the European dynasty of the House of Welf.

Historians assume that Hofhegnenberg was most likely built at the behest of the House of Wittelsbach around 1300 to serve as a bastion and as intimidation against the Bishopric of Augsburg. In 1296, the bishop of Augsburg had the Wittelsbach castle Kaltenberg destroyed. According to legend, Hofhegnenberg Castle was built with its stones. Ironically, the first written mention of the actual fortress dates to 24 October 1354, when the knight Winhart von Rohrbach bequeathed various tracts of land to the rulers of Augsburg, including nine hectares of land located outside the ‘Burg zu Haegniberg’.

15th and 16th Century: From a Century of Fruitless Administration to the Renaissance of Chivalry under Georg von Hegnenberg-Dux

Between 1399 and 1540 Hofhegnenberg was no longer under the rule of the Hegnenberg family but had instead been passed on as a fiefdom from one ducal guardian or overlord to another, resulting in the fortress being in disrepair when it once again came into the possession of the family of Georg von Hegnenberg-Dux’s (1509-1589) in 1542.

Georg von Hegnenberg-Dux was the illegitimate son of William IV, Duke of Bavaria. He primarily came to honour and fame as a knight of the Order of the Cross of Burgundy, but was also celebrated as the ‘fiery youth Georg’: He had already gained a reputation at the tender age of fifteen for showing remarkable courage during the Italian War of 1521–26. He later rescued Charles V (1500 – 1558), Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, from a Moorish ambush at the Battle of La Goleta, and thus enabled the Christian conquest of Tunis in 1535. Yet, before Charles V began to wage war against France, Georg requested exemption from service to finally return to his Bavarian homeland.

Upon his arrival in 1542, he received Hofhegnenberg as a fiefdom from William IV, Duke of Bavaria (1493 – 1550), and married a lady of the court, Wandula von Paulsdorf, in 1544.

When Georg returned to the battlefield during the Schmalkaldic War (1546 – 1547), he successfully served Emperor Charles V and thus contributed to the victory over the Lutheran opponents. He was well compensated by his father, the Duke of Bavaria, and was appointed governor of Ingolstadt, the strategically most important fortress in Bavaria at the time. In addition, Georg was awarded the prestigious accolade of Knight of the Order of the Golden Spur in 1554. In 1557, the progenitor to the noble family of Hegnenberg-Dux finally completed the renovation of Hofhegnenberg Castle and move in.

The achievements of Georg von Hegnenberg-Dux eventually reached their zenith in 1575, when Georg’s half-brother and the new successor to the Bavarian throne, Albert V (1528 – 1579), confirmed him as permanent governor of Ingolstadt and also enfeoffed him with Hofhegnenberg for his male descendants in perpetuity. The house of Hegnenberg thus advanced from ordinary vassals to high nobility, thanks to their relentless loyalty towards their rulers, a forbidden liaison and, of course, Georg’s strategic skill and chivalry.

Today, a life-size, red-marble statue of Georg von Hegnenberg-Dux can be found in the southern extension of the Chapel of Saint Mary, the adjacent Wilgefortis Chapel. The epitaph, commemorating the impeccable knight, was originally placed in the Franciscan church (today the hunting museum) in Neuhauser Street in Munich, and was moved to Hofhegnenberg after the Franciscan monastery was closed under Maximilian I. It is surrounded by a Renaissance aedicula and presents the deceased patriarch of the House of Hegnenberg in a confident powerful pose, hands on hips, and in full armour.

17th Century: The Thirty Year’s War and How Hofhegnenberg Became a Pilgrimage Site

On 23 May 1618, two Bohemian regents and their secretary were defenestrated during a Protestant insurgence that took place at the town hall of Prague. Fortunately, the three officials survived the 21-metre fall from the third floor. This particular incident entered the annals of history as the Second Defenestration of Prague and significantly influenced the history of Europe and marked the beginning of the religiously-motivated Thirty Years’ War fought between the Catholic League and the Protestant Union lasting from 1618 to 1648, devastating Germany.

Popularly also known as “Schwedenkrieg” (The War of the Swedes), the Thirty Years’ War became a turning point in German history which decimated one third of the country’s population. It was a war that brought disease, starvation, death, misery and devastation, sparing no one. Chaos came to the regions between Munich and Augsburg after Munich’s capitulation in 1632. The Swedes invaded and twice occupied the Brucker and the Wittelsbach land, once between 1632 and 1634, and again between 1646 and 1648, both times leaving destruction in their wake.

At this time, a particular incident is said to have occurred at Hofhegnenberg Castle. Although the tale is not substantiated by factual evidence, it has remained alive in the minds and memory of the local population to this day. The legend recounts the story of a Swedish riding squad which is said to have arrived at Hofhegnenberg during the first invasion. The men cooked stolen poultry on an open fire in the castle courtyard. One of the horsemen, it is said, took the gothic icon of the Virgin Mary from the altar and threw it into the flames. According to the legend, the icon lay in the flames for three hours but the heat and soot could not harm her, and she did not even turn black. Further attempts at burning the icon also failed. This annoyed the soldier so much that he ripped the Madonna from the fire and threw it away with a blasphemous slander. But, at the blasphemous act, his anger turned to sheer panic. The Swedes hurriedly gathered together their belongings and left. Thus, neither the chapel nor the castle were damaged and miraculously became the only place in the region spared from the war’s devastation.

The Madonna was returned to her rightful place, the altar of the chapel, where she stands to this day. The tale of this miraculous event soon spread beyond the borders of Hofhegnenberg and resulted in the castle and its chapel becoming a renowned place of pilgrimage.

The Gothic icon of the Blessed Virgin Mary and Child forms the centre of the chapel’s altarpiece and dates from the second half of the 15th century. The seated Madonna crowned by a Baroque aureole, augmented in the 18th century and decorated with eight putti seated on cumulus clouds, is framed by the arcade of the altar that surrounds the iconic image. The reredos dates from 1739. The adjacent figures on the altar, depicting Saint George and Saint Nicholas, were both created by the Bavarian iconographer Bartholomäus Kriechbaum (1643 – 1692) during the 17th century.

The Baroque frescos decorating the ceiling of the Chapel of Saint Mary, dating to approximately 1740, still bear witness to the legend of the miracle during the Thirty Years’ War.

18th Century: Peace and Prosperity at Hofhegnenberg Castle

A contemporary described Hofhegnenberg Castle:

“On Roßberg – the highest elevation halfway between Munich and Augsburg – Hofhegnenberg Castle is situated. Viewed from the southwest, it rises above its neighbouring estates, with a farmyard on the castle grounds, a small village of the same name, and a few farmhouses in front of it. The entire landscape is idyllic, with orderly fields and trees as far as the eye can see. The larger unit forms a park with a small pleasure garden and a pavilion in the centre – enclosed by a modest castle moat, which allows both the lord of the castle and the passers-by an undisturbed and unrestricted view of the property and the magnificent manor house.

The stone façade of the castle beckons from afar. The front view invites the onlooker to admire the gatehouse, framed by two small, decorative towers that make the rising belfry, just behind the gateway, appear a little less austere. Overall, the building complex is dominated by rectangular structures, consisting of five gable-roofed units, all different in height, thus conveying a playful impression without affecting the overall architectural clarity. In addition, the rear of the castle is characterised by the imposing bell tower and two further towers, the left of which is crowned by an onion dome roof characteristic of the German-speaking region near the Alps and is significantly higher than its shy twin on the right.”

This brief description of a picturesque setting is not based on a real location as such but on a three-hundred-year-old depiction of Hofhegnenberg Castle dating from 1701. It shows the castle grounds through the eyes of Michael Wening (1645-1718), a Bavarian court engraver known for his many depictions of important places in the Bavaria of his day.

It is unlikely that Wening’s work is a historically faithful representation. Wening liked to use various techniques that we would describe today as melange or pastiche, as he tried to merge different angles and perspectives into a single picture. But it was not illusion or unrealistic perfectionism motivating him. In fact, his creative process fell victim to financial cutbacks that forced the engraver to combine fact with fiction. Time and cost efficiency were required, because the production of copper engravings was not only time-consuming but also associated with high material costs. Accordingly, he had to bring as many aspects, angles and facets as possible into one single engraving, one single image. This task required more creativity and imagination than pure craftsmanship.

Regarding the historical origin and significance of Michael Wening’s copper engraving, a conspicuous detail must be mentioned. When Maximilian II Emanuel (1662 – 1726), Elector of Bavaria, commissioned the topography of Bavaria, he did not merely do so for regional and cultural studies but had something different in mind: promoting Bavaria elsewhere by displaying the country’s wealth. Since parts of Central and Northern Europe still bore the marks of destruction and devastation from the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), it was essential to win over talented artists, scholars, craftsmen, and even affluent investors. The economic and political development of Bavaria had to move forward. For this purpose, a detailed illustrated catalogue was without doubt more convincing than any elaborate pamphlet. And places such as Hofhegnenberg, with its magnificent courtyard castle, embodied the fundamental idea behind Max Emanuel’s project.

The 18th century was an overall uneventful, primarily peaceful time for Hofhegnenberg. The European coalition wars against Napoleon and revolutionary France had left Bavaria practically untouched till 1779 due to the duchy’s neutrality policy. In 1790, the Dolling branch of the lords of the Hegnenberg family was appointed imperial counts. In the same year, the castle’s western gateway was rebuilt in a neo-Gothic style, and this was in fact the last significant change to the structure of the core building.

19th Century and Beyond: Under the Spell of the French Revolution

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) and The Coalition Wars, which began in 1792 and lasted until 1815, only later left their mark on Bavaria and Hofhegnenberg. Profound changes followed after Maximilian I Joseph (27 May 1756 – 13 October 1825), prince-elector of Bavaria (as Maximilian IV Joseph) from 1799 to 1806, and Napoleon formed a friendly alliance between Bavaria and France in 1801.

On the one hand, Maximilian IV Joseph, prince-elector of Bavaria, who was heavily influenced by the Enlightenment, initiated the secularisation of the state of Bavaria in 1802 under the auspices of his progressive minister Maximilian von Montgelas (1759-1838). This resulted in the dissolution and expropriation of all monasteries and abbeys, as well as several other ecclesiastical institutions. The consequences of secularisation brought about one of the most powerful shifts in Bavarian history. This ground-breaking decision did not spare the Chapel of Saint Mary. Its significance ceased almost overnight, ending its hundred-year history as a pilgrimage site.

On the other hand, the alliance with Napoleonic France promoted Bavaria from duchy to kingdom in 1806. This in turn triggered the expansion of the state’s dominion with the annexation of the territories of Swabia, Franconia and parts of the Palatinate, as well as the declaration of Maximillian as the first king of Bavaria (as Maximilian I Joseph).

In its design, the garden landscape of the castle still reflects this change. In the 19th century, the alleged “baroque decadence” had to make way for an “exalted” serenity inspired by nature.

The majority of the landscape changes were implemented by the landscape architect Peter Joseph Lenné (1789-1866), the former protégé of Friedrich Ludwig von Sckell (1750-1823), the ingenious creator of one of the world’s largest urban parks, Munich’s English Garden. Lenné was however a prodigious mind himself, who not only mastered the art of garden design, but developed his unique signature by reintroducing stricter French geometries to his projects and blending these with idyllic and naturalistic sceneries. At the age of 26, Lenné was ordered to the Prussian court by Frederick William III of Prussia (1770-1840) and later became the imperial gardening engineer.

During his career, Lenné realised projects such as the creation of Berlin’s Tiergarten, Berlin’s most popular inner-city park, and was commissioned with the garden design of Sanssouci, a historic building in Potsdam, near Berlin, built by Frederick the Great, King of Prussia, as his summer palace. But above all, Lenné was commissioned to entirely redesign and add green areas in and around Potsdam and Berlin. Lenné revolutionised urban environments and recreation like none of his European peers and is still a driving force in inspiring contemporary landscapers. And also at Hofhegnenberg he was to implement his ideas.

With an area of 5 hectares, Castle Hofhegnenberg is a relatively small project within his oeuvre, as well as being one of his earlier works. The fascination and allure of the castle grounds is more subtle but still exceptional in documenting Lenné’s creative development.

One of the last notable descendants of the Hegnenberg-Dux branch, and landlord to Hofhegnenberg Castle, was the Bavarian politician Friedrich von Hegnenberg-Dux (1810-1872). Following the above-mentioned renewed European ideals that revolutionised the continental philosophical and political climate, he served as a representative of the Bavarian parliament (Landtag). He also became the first president of the chamber of representatives of the Landtag and remained in this position until 1857. Although he was a nobleman, he was one of the parliament’s liberal leaders and heavily promoted a new national political direction. This liberal spirit eventually inspired him to become a member of the Frankfurt Parliament, the first freely elected parliament for all of Germany, including the German-populated areas of Austria-Hungary, established during the German Revolution of 1848-49. After his retirement, he was appointed Bavarian State Secretary and Premier in 1871 and remained in this position until his death in the following year.

By the marriage of Otto Baron von Gebsattel (1855 – 1939) to the last descendant of the lineage, Countess Franziska von Hegnenberg (1848 – 1868), the Gebsattel family became the lords and owners of Hofhegneberg Castle in 1902. Before her death, after the devastating fire of 1865, Franziska commissioned the construction of a new farmyard to replace the old one which had become too small. The farmyard was relocated to the north of the property together with a brewery, farm buildings, stables, wagon shed, waterworks, inn for guests, and offices .

Throughout history, the population of the castle’s Hofmark, a demarcated district or area of aristocratic or ecclesiastical rulership, was frequently poverty stricken. A significant number of people were in need and, with a growing number of beggars as a consequence, they relied heavily on the local lordship’s benevolence. In contrast to the other feudal systems, the Electorate of Bavaria relied less on serfdom than on mutual trust and systematic administration. Bavaria was slightly ‘exotic’, as more than half of the territory did not belong directly to the Dukes of Bavaria. This resulted in a more libertarian allocation of responsibilities and thus made local nobility the unofficial rulers of their administered lands, granting them indirect autonomy. Almsgiving was quite a common practice for the lords of Hegnenberg-Dux in cooperation with the local clergy during the 18th and 19th century, as they tried to at least limit the growing number of beggars. Accordingly, the barons of Gebsattel took this duty very seriously and tended to incorporate charity into their daily actions.

The economic situation of the nobility had also deteriorated. Less focused on industry, but traditionally linked to agriculture and forestry, they were unable to increase their profits significantly. Due to high birth rates and the lack of wars, third, fourth and fifth-born children who did not inherit property, suffered economic difficulties, which is also reflected in Hofhegnenberg Castle. Poor relatives moved into the castle and had to be fed. The knights’ hall was divided into five separate rooms with lightweight walls to create living space. Relatives moved into the former servants’ quarters and handicraft areas on the ground floor. Mansards were even built in the attic.

The brewery had to be closed after a few years as it was simply unprofitable. Even today, brewing privileges registered in the real estate register still bear witness to this time.

THINGS TO KNOW & CURIOSITIES

Coat of Arms Room

The fully restored coat of arms room is a gem of the castle. It served as an anteroom to the actual judge’s chamber. The castle had the lower jurisdiction or Niedergerichtsbarkeit over the area. The lower jurisdiction usually dealt with land and testamentary issues, issues of matrimonial property regime, and minor civil matters. It had no criminal jurisdiction. Nevertheless, it was obviously intended to set the mood and create a sense of awe for the importance of the court. At least that is one explanation for the design of the coat of arms room.

The coat of arms room was built in the 17th century, with the last alterations undertaken in 1752. Located in the castle’s south-wing, halfway between the first and the second floor just above the chapel, the walls of the room are covered with wooden wainscotings painted in vivid colours from floor to ceiling. The historical chronogram depicts nearly 200 coats of arms of ruling dynasties, including those of the Holy See, cardinals, prince-bishops, and emperors. Some fictitious coats of arms were also creatively added, probably to lend the court a more exotic and cosmopolitan appeal. Extravagant-looking and elaborate in illustration, the hall is the epitome of noble representational interior design, self-fashioning, and internationality. It is undoubtedly a room that today serves as a lively gateway to history.

Michael Wening

Similar to his illustration of Hofhegnenberg Castle, Michael Wening created about 1000 vedute of Bavarian towns, castles and monasteries for the four-volume topography, Historico-Topographica Descriptio Bavariae, on behalf of Maximilian II (1662 – 1726), also known as Max Emanuel or Maximilian Emanuel, a Wittelsbach ruler of Bavaria and a Prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire.

The engravings, created between 1701 and 1726, were augmented by textual descriptions by Wening’s contemporary, Ferdinand Schönwetter, a Jesuit priest. For today’s scientists, Historico-Topographica Descriptio Bavariae is crucial to understanding developments in the field of topography. Nevertheless, Wening’s lifework not only gained importance because of his topography, but also because of his meticulous interpretation of the Bavarian way of life at the beginning of the 18th century. His petit genre paintings portrayed aspects of everyday life beyond the limits of social status, from beggar to nobleman, equally reproducing town and country life. In the light of Wening’s historical relevance, it is all the more important to mention that a copy of Historico-Topographica Descriptio Bavariae forms part of the castle’s collection.

Comparing the modern condition of the castle with its appearance around the 1700s, primarily changes in the landscape are visible: The pleasure garden including its pavilion, the extensive bulwark surrounding the castle grounds, the strict geometry, and the baroque theatricality created space for a clearly structured informality inspired by nature. The original stock of trees has been preserved, and the historic pathways have now been restored, giving the residents of the castle the opportunity of taking a pleasurable extended walk. Parts of the vaults, earthworks and redoubts of the old bulwark are still extant. The rectangular farmyard was moved from the southeast to the northeast.

Ancient Burial Grounds

The Hofhegneneberg castle complex holds many secrets and mysteries yet to be revealed. For a long time it was believed that the earth mounds located in the southern part of the estate might be ancient burial mounds. Such geological structures cannot be found in the area, and they also do not seem to have an Ice Age origin. Such burial mounds are usually found on the most prominent elevations in a region, probably because of the idea of being particularly close to the sky. In fact, these barrows, with a radius of approximately 6 meters, are located on the highest elevation between Munich and Augsburg. An additional plausible reason for this speculation is the fact that these mounds are covered by venerable linden trees which were sacred to the Teutons and are often found covering their burial sites.Archaeological findings in area of the present-day district of Aichach-Friedberg district also indicate that this area has been inhabited for at least ten thousand years. In addition, it is documented that the Germanic tribes of the Alemanni and the Bavarians settled in this territory towards the end of the 5th and the beginning of the 6th centuries when Roman rule over the province of Raetia ended. As a sign of respect and differentiation, it was characteristic among the Germanic tribes to bury their most important members in burial chambers below large burial mounds. Often the dead were given grave goods such as food, valuable gifts, clothing, jewellery, and weapons. Surveys with ground-penetrating radar provided the information necessary to prove or disprove this theory without damaging or endangering the existing heritage substance or any underlying archaeological treasures.

The Old Brewery & Secret Passages

The castle’s adjoining farmyard, which was previously located on the west side of the estate, was rebuilt and expanded on the northern side in the 19th century. The reason for the relocation of the farm was a devastating fire in the former brewery in 1877, which was also located in the west. The fire was furthermore key to the establishment of the local fire department in the same year.

The new farmyard began operations in 1867, as well as the new brewery and malt house. The brewery soon proved to be unprofitable and production ceased as early as 1900.

Many cellar vaults and basement rooms are hidden beneath the present brewery building, extending over two floors underground and which by far exceed the necessary storage capacities of even the largest breweries.

There continues to be an extensive tunnel system with escape routes hidden under the farmyard, but most of these corridors are no longer accessible as they have either collapsed or were walled up. The passages are in the process of being exposed. Local experts have long speculated that these secret passages originally led to neighbouring Althegnenberg or even extended further to Kissing near Augsburg which is 14 kilometres away.

Ghosts

Some residents of Hofhegnenberg village swear they saw a white woman on the castle grounds. She supposedly not only haunts the corridors and cellars, but also the attic of the castle.

The underground ammunition factory

Rumors and tales about an underground ammunition factory in the brewery area during the Second World War persist. Numerous installations from the 1940s do, in fact, exist but no concrete evidence has yet been found.

Filming location for TV series

From 1988, the old castle served as the backdrop for the fictional Bernried Castle in Küblach in the Bavarian Forest for the TV series Forsthaus Falkenau. After numerous main actors left the series in 2006, including the fictional residents of the castle, it was no longer shown or mentioned in the series. The castle also served as a backdrop in other television series.

ARCHITECTURE

Overall Structure

Historians believe that Hofhegnenberg Castle was most likely erected by the noble Wittelsbach family and it was first officially documented in 1354. Two centuries later, the original medieval fortress had been replaced by a castle. It displays the transition from a fortress built for defense to a prestigious castle, which was no longer only used for fortification and protection, but also for the creation of sophisticated internal social spaces.

Hofhegnenberg Castle is characterised by a remarkable overall structure with an intriguing architectural assortment consisting of stylistic elements ranging from Medieval to Renaissance, Baroque and even Neo-Gothic. Several elements within the complex date as far back as the 16th and 17th century, such as carved-stone coats of arms of the noble Hegnenberg family embellishing various areas of the façade. One of these can be found in the inner courtyard next to the massive wooden portal leading to the Chapel of St Mary, incorporated in the castle’s north wing. The four-winged main complex, which is dominated by rectangular structures, comprises five gable-roofed buildings, all varying in height, with several towers, taller than the other structures. On the western side there is a Neo-Gothically altered gateway building, framed by two smaller towers, one of which is crowned by an onion dome. The adjoining farmyard was once located on the western side of the estate but relocated and entirely rebuilt during the 19th century to the north, where it still stands today.

The first renovations to the castle were completed by 1557. Details of this period are still recognisable in the entire architecture of the castle. A dendrochronological analysis of the roof timbering revealed that the roof structure and the materials utilised date from the mid-16th century.

The surrounding 19th century landscape garden in itself presents a heritage site. Designed by Peter Joseph Lenné, the imperial gardening engineer to the Prussian court and prodigious landscape architect, and with an area of 5 hectares, it is a relatively small, more subtle project within his oeuvre, but still demonstrates his unique signature style combining strict French geometries with idyllic and naturalistic sceneries.

Chapel of St. Mary

The former pilgrimage site of the Chapel of St. Mary, originally built during the 16th century reconstruction process, today serves as a link between the different construction periods and stylistic epochs of Hofhegnenberg. Located on the ground floor of the castle’s southeast corner, the square nave measures 10 x 10 metres, and has a central pillar and four cross vaults above. The Gothic icon depicting the Blessed Virgin Mary with Child, the namesake of the chapel, forms the focal point of the chapel. The origin of the Madonna is dated to the second half of the 15th century. A golden baroque aureole, the reredos, was added in 1739. There is an exceptional collection of liturgical gowns, crowns and sceptres from the 18th century when the chapel was an important and renowned pilgrimage site, and these items are still used to decorate the icon on various Catholic holidays.

The baroque chapel impresses with its radiant, gold-leaf altar elements and individual ornaments evenly distributed throughout the entire room. The altarpiece is adorned with eight putti sitting on cumulus clouds, while the arcade of the altar frames the iconic Madonna. There are two wooden life-sized figures on either side of the altar, depicting Saint George and Saint Nicholas, both of which were created by the Bavarian iconographer Bartholomäus Kriechbaum. A baroque sculpture depicting the Archangel Michael to the left of the altar, and one of St. John of Nepomuk on the right, characterise the side altars. The frescos decorating the ceiling which, according to the dating from 1751 originate from the Swabian master Ignaz Paur, illustrate the history of the Chapel of St. Mary as a pilgrimage site, as well as portraying the miraculous legend of Hofhegnenberg’s Madonna during the Thirty Years’ War. The adjacent Chapel of St. Wilgefortis, constructed in 1751, two centuries after the main chapel, houses a red marble epitaph of Georg von Hegnenberg-Dux, surrounded by a Renaissance aedicula. The epitaph was originally placed in the church of the Franciscan monastery on Neuhauser Strasse in Munich but was moved to Hofhegnenberg after the monastery was closed.

Characteristic Features

The previously collapsed defence tower in the south-western corner reveals the original bossage at the base, while being optically separated from the rest of the structure above by a visible joint incorporated into the brickwork of the tower. From this visible joint upward, the tower was rebuilt. One of the most intriguing details of the tower lies in the original lower part of the construction, as it was built as a so-called palas, a prestigious or imposing building containing a great hall, much like the Roman aula, with walls more than two metres thick. The defence tower was rebuilt to its original height of just over 40 meters and returns a sense of harmony to the castle. From the top level one has a clear view of Augsburg, 20 kilometers away.

The east-facing arcades in the inner courtyard also bear witness to the dominant Renaissance style of Hofhegnenberg. Four large pointed arches are supported by simple pillars on the ground floor of the west wing, and the façade on the first floor comprises six smaller, round arches supported by Tuscan columns, forming an open gallery. A faded indigo was selected for the delicate ornamentations of the gallery’s columns and parapets.

According to historical sources, the south wing with its knights’ hall was constructed during the 17th century. Stone slabs from Solnhofen in Middle Franconia in Bavaria, a Jurassic limestone region, still form the original flooring material, as on the entire first floor.

The heavy black 16th century cockle stove in the knights’ hall is one of the oldest objects in the entire castle. It is however not clear where it originally stood, as it predates the knight’s hall by a century.

Further specific Renaissance details remaining in the castle include the original door fittings as well as two typical Bavarian 16th century façade cabinets. Furthermore, a secret passage leads from the knight’s hall directly to the coat of arms room located above the chapel.

The coat of arms room was built during the 17th century, with the last alterations having been undertaken in 1752. The walls are covered with wooden panelling entirely painted in a historical chronogram depicting almost two hundred of the world’s oldest coats of arms from European noble families and clergy.

Two of the few objects saved from the original inventory of Hofhegnenberg are the baroque paintings by Franz Joachim Beich (1666 – 1748), who excelled in painting landscapes and battles. Today, these two paintings decorate the ‘red salon’ in the north-wing and are exhibited alongside works by Beich which The European Heritage Project managed to acquire and incorporate into its collection.

The European Heritage Project purchased two 18th century cannons bearing the crest of Hegnenberg-Dux, which are now displayed in the inner courtyard.

STRUCTURAL CONDITION AT TIME OF ACQUISITION

RESTORATION AND CONSERVATION MEASURES

Structural elements

Dendrochronological examinations of wooden structures, such as roof beams, were carried out to determine the precise age of the building elements and individual structures. These examinations were not only important for general historical estimates but also to ensure reliable structural and safety measures.

Unfortunately, one of the original farmyard buildings could not be saved and was torn down due to the roof collapsing. The major part of the farmyard has nonetheless been successfully rebuilt and now accommodates a riding stable with a stud. The historic brewery was reconstructed, with the roof and fold structurally renewed in its entirety.

Heating

During the floor renovation process, underfloor heating was installed because, unlike ordinary heaters, this solution would preserve the authentic historic appearance of the rooms. The apartments in the attic were not only equipped with underfloor but also in-wall heating. In order to ensure comfort even during the cold winter months, a low-energy heating system was also installed in the castle’s St. Mary chapel.

Flooring

The Solnhofen stone slabs were retained as original flooring material, while broken or missing slabs were reintegrated.

Masonry

One of the most demanding restoration measures during the renovation was the completion of the defence tower at the south-western corner of the castle. While this endeavour was to be addressed from day one, it was the last task to be completed. Finally, in 2012, and according to old building plans, the castle’s lost symbol of power resurged, newly painted, in its former glory. An elegant and considerate solution in honour of the past was implemented in the masonry of the tower, revealing the original bossage at the base, yet clearly separating it optically from the new superstructure by a visible joint. By showing the join between the old and the new masonry, an intentional contrast was created, serving as a positive reminder of the tower’s temporary decay.

Various dilapidated interior walls had to be removed, rooms reworked, and subsequently steel reinforcements installed in exposed supports to reinforce dilapidated structures. Exterior walls were plastered with insulation material. The exterior masonry required a general overhaul, starting with the removal of fragile elements that were later reconstructed, realigned and reinforced or replaced entirely with replicas.

Special attention was paid to the Renaissance arcades in the courtyard. While four large pointed arches supported by simple pillars were clearly visible on the staircase of the west wing, the arcade corridor on the first floor was completely walled up, presumably a measure intended to ensure better heating of the castle. Six smaller, round arches supported by Tuscan columns, forming an open gallery, were hidden behind walls that were subsequently torn down. The entire Renaissance gallery was thus exposed and made visible again. The columns and parapets of the gallery ultimately reflect the golden age of the castle. The carefully selected pale indigo colour reappears in the colour of the castle’s doors, creating a uniform and graceful image. The stately knight’s hall in the west wing has also been restored to its original condition, and the lightweight walls, built in the 19th century, were removed.

PRESENT USE & FUTURE PLANS

Hofhegnenberg has always been a location of regional importance and an accessible castle. The residents of the neighbouring village of Hofhegnenberg perceive the castle as their own, and, in this respect, it was important to once again allow them access.

Hofhegnenberg still opens its gates to visiting local school classes or liturgical events held at the chapel of St Mary.

With as many as 1000 pilgrims, the chapel is open to the public for a solemn procession followed by prayer in honour of the Blessed Virgin Mary in May. The European Heritage Project thanks the population for the good collaboration with an agape.

Every year, at the beginning of December, the premises of Hofhegnenberg are decorated in a festive fashion and the castle’s gates opened to the public, when the traditional Kipferlmarkt takes place in the courtyard on the second weekend of Advent. Visitors can enjoy Christmas specialities, sweet delicacies, hot apple strudel, goulash, or fried sausages in a bread roll, as well as warming beverages, but, mainly the Kipferl biscuits are sold at this very intimate and warm Christmas Market. The market is organised with local associations which can present themselves to the public.

All proceeds from the bazaar are, of course, donated to charity. The European Heritage Project, for example, operates the mulled wine stand and donates the profits to three to five needy families in the region.

The renovated castle is a place of togetherness and gives the village a feeling of continuity.

THE FARMYARD

History and condition

Next to the castle is the old farmyard with a usable area of around 4000 square meters. This was only built in the 19th century after the previous building on the west side had become too small. The original four-sided building complex contained stables, sheds and granaries for the agricultural business as well as the so-called chancellery, where the administrative functions were concentrated. At the end of the 19th century, the castle’s own brewery was established, but this was closed down after a few decades before the First World War for economic reasons. The entire area was extensively cellared. There is a two-storey vaulted cellar beneath the brewery, which was mainly used to store ice for the beer. Numerous underground tunnels run through the grounds and in some cases also leave the castle area. Their destination has yet to be researched. With the decline of agriculture, the farmstead also lost its importance and fell into disrepair. In the middle of the 20th century, the north wing of the complex collapsed and was never rebuilt. In 2020, the northern part of the east wing had to be demolished for structural reasons.

Construction measures

The entire complex was in a ruinous state. Therefore, the first measures concentrated on securing the substance. Roofs were renewed, window openings closed and load-bearing parts reinforced. Subsequently, the entire complex was renovated from the ground up.

In 2023, the demolished part of the building in the east wing was reconstructed with a cubature greenhouse. Planning permission was obtained for the collapsed north wing. The building gap is to be closed here and the old building situation restored.

Utilization

A new utilization concept has been drawn up for the Wirtschaftshof, which provides for the involvement of the public. The brewery building is to become part of a hotel complex, which will also include the new north wing as a reception area and a castle restaurant, consisting of a beer garden in the courtyard area and an upscale restaurant in the north wing.

Videobeiträge:

Seit zwei Jahren müssen die Münchner auf ihre Wiesn verzichten. Auf Schloss Hofhegnenberg hat das European Heritage Project nun ein eigenes Oktoberfest für rund 250 geladene Gäste veranstaltet. Unter Wahrung der 3-G Regeln konnte endlich wieder in zünftiger Atmosphäre gefeiert werden!

Jedes Jahr lädt das European Heritage Project die Anwohner der umliegenden Gemeinden zur Marienprozession nach Schloss Hofhegnenberg ein. Nachdem die Veranstaltung im vergangenen Jahr pandemiebedingt ausfallen musste, konnte die Tradition, die auf einer Legende aus dem 17. Jahrhundert beruht, nun wieder stattfinden.

a.tv vom 27.11.2019: Im Wittelsbacher Land – Eierlikör auf Schloss Hofhegnenberg und Dasinger Adventskränze