The Vergenoegd Löw wine estate, dating from 1696 and built in the historic Cape Dutch style, is one of the oldest representations of the early Dutch settlement history in South Africa.

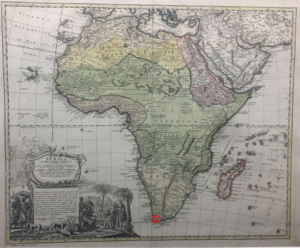

Vergenoegd Löw The Wine Estate is located along the Stellenbosch Wine Route, on the Eerste River, only 40 kilometres from Cape Town in the South African region of the Western Cape. The manor house overlooks the Helderberg mountain range to the east, and Table Mountain to the northwest.

In 1696, the vrijburger (free citizen), Pieter de Vos Vrijburg received the previously uninhabited and abandoned land of what would later become the Vergenoegd Löw wine estate from the Dutch East India Company. The company aimed to secure its trading post in Cape Town by establishing a settlement. Immediately after the acquisition by de Vos, Vergenoegd, as it was known then, was already documented as an agricultural enterprise. The inventory showed that wine-growing was already practiced at the time. This makes Vergenoegd Löw one of the three oldest existing wineries in the southern hemisphere of the African continent.

The historical core of the estate is situated on a yard, a so-called werf, and consists of various farmhouse buildings alongside original workers’ accommodation.

What distinguishes Vergenoegd Löw, in addition to its rich history and top-quality oenological plants, is the well-preserved building fabric which has remained largely unchanged since its construction. Vergenoegd Löw, built in the Cape Dutch or traditional “Afrikaner” architectural style, i.e. the Dutch-inspired construction method of the Dutch-Boer settlers, is a testament to the earliest Dutch settlement history in South Africa,.

Today, Vergenoegd Löw is not only one of the most valuable cultural assets and monuments in the country; the South African government announced in 2021 that Vergenoegd Löw will be registered on the UNESCO list of world heritage sites.

MORE | LESS

When the Faure family, an original settler family of French descent, had to give up the Vergenoegd estate in 2015 after 14 generations of family ownership, The European Heritage Project became aware of the culturally valuable estate which is home to one of the oldest and largest wine estates in South Africa.

The the last generation of the Faure family was no longer financially able to make the required investments leaving the estate in poor condition due to decades of neglect. The equipment was derelict and partly no longer functional. Alterations to the building substance that are otherwise frequently encountered were therefore also absent, which turned out to be an advantage. The entire property embodied a largely unadulterated, if ruinous, example of the early South African settlement culture.

The extensive restoration and preservation measures were largely completed in 2021. In doing so, attention was not only paid to the cooperation with the monument protection authorities, but also to a sustainable reactivation of agriculture. Various projects promoting biodiversity and the preservation of nature reserves, as well as contributing to the ongoing improvement of water quality and energy efficiency, have been implemented.

Today the estate is home to numerous water birds, including one of the largest populations of runner ducks worldwide. The Vergenoegd Löw wine estate has become one of South Africa’s the largest pioneering showcase projects for its support of local biodiversity, the use of renewable energies, the improvement of the water quality, and much more. For its commitment, Vergenoegd Löw was awarded World Wildlife Fund Conservation Champion status.

PURCHASE SITUATION

When The European Heritage Project bought the Vergenoegd Löw wine estate in 2015 from the Faure family, the owners since 1820, the Board of Trustees was instantly fascinated by the estate’s impressive history dating back to 1696.

Although well-known for their excellent wines in the past, wines that were even served regularly at state receptions, the last generation of the Faure family missed the changeover to more modern methods of winemaking. Outdated manufacturing processes ultimately caused the quality of the wines to deteriorate and profits to decrease. Latterly, only tank wines with low margins were produced. The critical financial situation made investments in the buildings and work equipment impossible. The last remaining historic stables and barns in the entire Western Cape region which had remained unchanged since the beginning of the 18th century were on the verge of collapse. The Faure family faced financial ruin.

The European Heritage Project was able to intervene in this situation. With the agreed purchase price, the Faures were able to settle their liabilities. The European Heritage Project not only acquired one of the most beautiful and historically valuable wine farms in South Africa, but, after the renovation of the production facilities, one of the best wines in the country.

REAL ESTATE FACTS & FIGURES

The Vergenoegd Löw wine estate is part of the well-known wine-growing region of Stellenbosch in the Western Cape region of South Africa. It is located a few kilometres from the ocean and the sandy beaches of Somerset. Cape Town is approximately 40 kilometres away and the international airport only 15 kilometres. The estate is easily accessible via the developed network of expressways.

Vergenoegd Löw covers about 180 hectares of land adjacent to the Eerste River. The area is predominantly flat with a difference in elevation of only five meters.

The estate has extensive water rights on the Eerste River, allowing it to remain unaffected by the droughts of recent years. The two large lakes on the property are used as water reservoirs and are filled by the nearby river, but mostly by heavy rainfall in winter.

The estate includes the farmstead with the main house and other buildings, as well as 170 hectares of agricultural land, mostly used for vineyards.

After the renovation of the winery, the wine estate produces up to 350,000 litres of wine annually, which is shipped all over the world. The most important grape varieties grown are Shiraz, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, and the wines are produced on the estate.

A significant portion of the estate is a Provincial Heritage Site. The historical farmstead from the transition period from the 17th to the 18th century was declared a National Monument. This essentially includes the manor house, three barns, a cottage, the former slave quarters including the freestanding slave bell, as well as the werf. What remains of the prehistoric kraal is still visible in the form of wall remnants.

The wine estate consists of two 18th century barns, the winery from the 1920s, and an additional modern warehouse built in 1980. In 2020 the winery was expanded considerably and a warehouse added.

Modern guest houses have been carefully integrated into the landscape. The usable areas of all buildings add up to more than 5,000 m².

The Deli, a restaurant for day-visitors offering inexpensive snacks outdoors, has opened in front of the historic slave bell.

An upmarket restaurant, Clara‘s Barn, is due to open in September 2021 in one of the restored barns.

Wine tastings and cultural events take place in the manor house and the winery.

Approximately 15,000 guests visited the estate In 2019. The daily parade of 1,500 Indian runner ducks making their way through the farmstead to the vineyards to “work” by foraging for snails and insects particularly impresses the guests.

HISTORY

Early Settlements and the Dutch Cape Colony

Literally translated, the Dutch word “vergenoegd” means “contented”. This name was given to his new farm in the Dutch Cape Colony in 1699 by the Dutch settler Pieter de Vos, a member of the Dutch Reformed Church of Stellenbosch.

The Kaapkolonie, or Cape Colony, named after the Kaap de Goede Hoop, Cape of Good Hope, was a Dutch colony established in 1652 by the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC). A Dutch expedition led by Jan van Riebeeck (1619-1677) established a trading post and naval victualing station for the ships of the Dutch East India Company on their long journey between the Netherlands and Asia. Within three decades, the Cape had become home to a large community of ‘vrijlieden’, or ‘vrijburgers’, the free citizens of the early Cape Colony, mostly former employees of the Dutch East India Company, who settled in Dutch colonies after completing their service contracts. The vrijburgers were mostly married Dutch citizens who undertook to spend at least twenty years farming the land. In exchange they received tax exemption status and were loaned tools and seed. The early trading companies were the first multinational companies in the world and thus, the vrijburgers, apart from the Dutch, included Scandinavians and Germans In 1688 almost 200 French Huguenots who had fled to the Netherlands due to religious persecution in their homeland poured into the Cape Colony after the Edict of Fontainebleau (1685) revoked the Huguenots’ right to practice their religion without persecution from the state.

Dutch customs and the Dutch language dominated the daily lives of the settlers and were quickly adopted by other immigrants.

Over time, the Dutch settlers, now known as “boers” (farmers), moved deeper and deeper into the country far beyond the initial borders of the Cape Colony. Some adopted a nomadic lifestyle and were called trekboers, wandering farmers or nomadic pastoralists. Repeated bitter conflicts occurred between the advancing settlers and native tribes such as the Khoisan and the Xhosa who were defending their territory.

The Dutch settlers imported thousands of slaves to the Cape of Good Hope from other Dutch colonies and other parts of Africa as cheap labour. By the end of the 17th century the population of the Cape Colony had risen to about 26,000 settlers of European descent and approximately 30,000 slaves.

From Outpost to Farmstead

Vergenoegd was owned by Pieter de Vos for only a year before he transferred the lands to Ferdinant Appels (1655-1717). After the sale, Vergenoegd remained in the possession of the Appelt family, who built up an agricultural estate, for 40 years. After the death of Ferdinant Appels, the estate passed to his widow, who later remarried. Her husband Johannes Colijn, also called Johannes Oberholzer, was a Swiss emigrant and was listed as the subsequent owner of the estate.

When Ferdinant Appels passed away in 1717, the inventory of his estate indicated a well-developed farm. He owned 165 cattle, 795 sheep, 18 pigs, 13 horses, and 10 slaves, as well as numerous wagons, ploughs, and other agricultural equipment. Furthermore, the inventory included numerous household items, wine-making vats, and so forth. Although there is no description of the buildings, it can be inferred that the farm included a family dwelling, accommodation for the slaves, and several barns. There is likely to have been a large enclosure or kraal system for the cattle

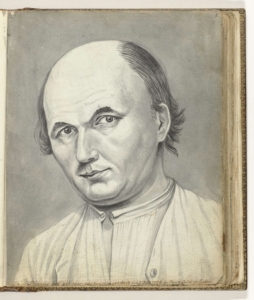

With the widow’s marriage to Johannes Colijn (1710-1767), Vergenoegd remained in the family until 1782, when the estate was sold to Johan Georg Lochner. The Lochner family hosted the Dutch clergyman and watercolourist Jan Brandes (1743-1808), who visited Vergenoegd four years later and created several charming watercolour paintings of the property.

After the sale of the farm by the Lochner family, the property changed hands several times for short durations between 1789 and 1820, until it was sold to the Faure family in 1820.

Winemaking in the Cape Colony

Jan van Riebeeck founded the Cape Colony in 1652 primarily as a supply station for ships passing the Cape of Good Hope on their route between Europe and Asia to take on fresh water and fresh produce. Gradually, it was recognized that a lack of fresh fruit and vegetables was responsible for the dreaded seafarer disease scurvy. Not only fruit and vegetables were used to combat scurvy, but wine had also proven to be an effective preventive agent. The first vineyards were planted in the Cape Colony and in 1659 the first wine was produced. At the same time a group of settlers travelled inland across the ‘sandy wastelands’ to trade with the indigenous Khoikhoi and discovered the Eerste River (meaning first river).

In 1679 Simon van der Stel (1639-1712), the new Dutch governor, arrived in the Cape Colony. He followed the Eerste River upstream to ascertain the farming potential of this area. Shortly thereafter the first land was granted to farmers, and Ferdinand Appels began planting vines along the Eerste River, benefitting from van der Stel’s expertise. The governor and wine connoisseur established a committee to advise the winegrowers during the harvest.

South African viticulture experienced its first boom around 1760. The settlers were wealthy and made significant improvements to their estates. They built new homes, enlarged existing homes and provided the houses with impressive gables.

The quality of wine was, however, poor. It was not until the arrival of Sir George Yonge (1731 –1812), Governor of the Cape Colony from 1799 to 1801, that progress was made. Yonge employed wine tasters who inspected and tested all wines entering Cape Town and rejected unsatisfactory wines At the time, the French Faure family had entered the country and had already established themselves as winemakers on several estates in the region before they took over the Vergenoegd estate in 1820.

From religious persecution in France to becoming vrijburgers in the Cape Colony: The Faure Family

The progenitor of the South African branch of the Faure family was Antoine Alexandre Faure (1685-1736). Antoine was born in the town of Orange, Vaucluse, in Provence in the south of France, in the year that the Sun King, Louis XIV of France (1638 – 1715), revoked the Edict of Nantes, which had granted the Huguenots the right to practice their religion without persecution from the state. Louis XIV replaced the Edict of Nantes with the Edict of Fontainebleau which banned all Protestant worship, deprived Protestants of their civil rights, and prohibited them from buying property. Antoine’s parents, Pierre Faure (1636-1703) and Justine Pointy (1653-1700), fled to Borculo in the Netherlands with their one-year-old son Antoine, where he grew up .

The Faure family returned once to Orange when peace was restored in 1698 with The Peace of Ryswick (or Rijswijk) before having to flee again. After the death of his wife Justine, Pierre settled with his daughter in Switzerland. Antoine later fled via Switzerland and Prussia to Bergen op Zoom in the Netherlands where he worked as an assistant to a doctor. In 1713, Antoine was engaged as a soldier by the Dutch East India Company for five years. He left the Netherlands on the ship Kockinge and arrived at the Cape of Good Hope on 24 March 1714 where he was appointed as a secretary. In 1716 he married Rachel de Villiers (1694-1773) and their first son, Abraham Faure (1717-1792), was born a year later. In 1718, Antoine was granted citizenship as a vrijburger of the Cape Colony. He was appointed as teacher, reader and precentor at the Stellenbosch Dutch Reformed Church in 1719 and moved with his family to Stellenbosch, east of Cape Town. After his death in 1736, his son Abraham took over the position. Antoine and Rachel had seven children.

The Faure Family at Vergenoegd

Jacobus Christiaan Faure (1769-1834), one of Abraham Faure’s seven children, inherited land from his father and went on to purchase many more grape farms. In 1820, his son, Johannes Gysbertus Faure (1796-1869), bought Vergenoegd from the Lutheran minister Johan Georg Lochner and was thus the first member of the Faure family to own the farm. The farm originally consisted of 59 morgen (approximately 15 hectares), and was increased over the years by the Faure family to around 1,000 morgen (approximately 250 hectares). The family also owned another estate called Rustenburg in Firgrove between Somerset West and Stellenbosch. Johannes Gysbertus owned Vergenoegd until 1847 when he moved to Rustenburg and sold it to his younger brother, Jacobus Christiaan Faure Junior (1798-1876), who lived in Stellenbosch.

Jacobus Christiaan Junior had two children with his first wife Elisabeth Brink, and six children with his second wife Elisabeth Myburgh. Like the rest of the family, Jacobus Christiaan Junior was a religious man and was a member of the Stellenbosch Dutch Reformed Church. It is recorded that he transported a new pulpit for the Stellenbosch church by wagon from Cape Town in 1853. In 1872 he passed Vergenoegd on to his second eldest son, Johannes Albertus Faure (1838-1902) to retire.

Johannes Albertus Faure presumably worked on the farm Vergenoegd as well as at Rustenburg, which was sold in1868. He served as a member of the Legislative Assembly of the Cape Colony for 12 years and was a member of the colonial parliament. In the Cabinet he served as Minister of Native Affairs. His wife Anna Frederika Wilhelmina Brand (1839-1920) was the sister of Sir Johannes Henricus Brand (1823-1888), the President of the Orange Free State, or Oranje Vrijstaat. The Orange Free State was an independent sovereign Boer republic in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Empire at the end of the Second Boer War in 1902.

Johannes Albertus Faure and his wife Anna had five children: Jacobus Christiaan, called Kosie, (1861-1934), Anna Fredrika Wilhelmina (1863-1932), Elizabeth (1865-1944), Wilhelmina Catharina Johanna (1868-1947), and Philippus Albertus Brand (1875-1947). The eldest son, Jacobus Christiaan (Kosie) (1861-1934) inherited Vergenoegd and farmed wine grapes and kept cattle and horses. Many horses from Vergenoegd were supplied to the British during the Second Boer War between 1899 and 1902. In 1896, aged 35, Kosie married Alice Maud Cawood (1868-1914) and they had two children: Erilda Louisa (1898-1968) and Johannes Albertus (1900-1967).

Erilda Louisa married William Charles Starke (1894-1988), a wine maker in Muldersvlei, Klapmuts, and her brother Johannes Albertus, called John, inherited the Vergenoegd estate. John cultivated quality grapes and crafted wines of excellent quality which won many awards and were served at state receptions. At the age of 30, John married Elaine Constance Brand. John and Elaine had 3 children: Rosalie Ida (*1932), Jacobus (Jac) Christaan (*1934), and Johannes Henricus Brand (1938-2007), called Brand. The brothers Jac and Brand inherited Vergenoegd and continued their father’s success and produced many award-winning wines. The three children of Jac and Brand inherited Vergenoegd in equal parts. The eldest son of Jac, Johannes Albertus (*1962), called John, sold a portion of the farm in 2010 to the City of Cape Town for the Cape Town Film Studios. The remaining part of Vergenoegd was sold to The European Heritage Project after the economic decline in 2015. Vergenoegd became Vergenoegd Löw.

THINGS TO KNOW & KURIOSITIES

Jan Brandes and his panoramas of Vergenoegd

The Dutch clergyman and watercolourist, Jan Brandes (1743-1808) spent a year at Vergenoegd during which time he created three watercolour panoramas of the estate, one of which includes the building itself. These panoramas are deemed to be accurate renditions and are now digitally available in high resolution at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. They have proved to be an important resource which depicts the property in good detail as it was circa 1786. It is very seldom that graphic detail of this kind is available for any Cape farms. While certain elements of the panorama cannot be explained by what is on the ground today, it is largely very accurate down to verifiable details of the cellars, homestead, walled ‘kraals’ and even the formal garden in front of the homestead, which is still in place today. The panorama serves to confirm that Vergenoegd belongs to the most intact early Cape farms and can therefore, without doubt, be classified a very important heritage site of not only regional, but national significance.

Runner Ducks

Vergenoegd Löw The Wine Estate is famous for its use of Indian runner ducks as part of a natural pest control programme. The ducks “work” in the vineyards by foraging for snails and other insects. More than 1,500 ducks are herded into the vineyards daily. The duck parade to and from the vineyards has become a major public attraction at the Vergenoegd Löw wine estate.

WWF Conservation Champion

Together with experts, the project is committed to sustainable agriculture and the preservation of biodiversity by protecting natural landscapes. Today, nature is seen as a valuable part of local and regional culture, and water and energy are used more efficiently.

Every process on the wine farm is designed to leave as light a footprint as possible. This starts with a deep respect for the land and every creature that calls it home. All processes such as recycling, creating biodegradable and recyclable packaging, utilising solar electricity, composting, and utilising low-water drip irrigation systems from the water treatment plant on site, have earned the farm the honour of WWF Conservation Champion status, and IPW (Integrated Production of Wine) biodiversity certifications.

Unique geographical location of the vineyards

The topography of the famous vineyards of the world differs significantly from the conditions at Vergenoegd Löw. They are usually located on steep slopes to ensure good ventilation of the grapes, thereby protecting the grapes from rotting.

The predominantly south facing slopes improve the angle of the sun and give the grapes the energy they require to develop enough sugar, and the grapes benefit from abundant rainfall in the growing season.

None of these conditions exist at Vergenoegd Löw. And yet, top wines have been produced here for centuries. How can that be?

Vergenoegd Löw is located on a plain that opens to the nearby ocean. The cold water from the South Pole and the warm landmass cause strong winds that blow onshore during the day and offshore at night. These “blow dry” the grapes and prevent the formation of fungi. The high salt content in the air also has an antiseptic effect.

The solar radiation is very intense, whereby an increased angle of the sun rays due to a hillside location is not necessary. On the contrary: the exposure to the sun is so strong and the number of sunshine hours so high that wines which are particularly in need of sunshine, such as Shiraz, can mature extremely well.

There is also no heavy rainfall during the growing season. Another natural phenomenon, however, promotes ripening. Every year the Eerste River overflows its banks and floods the vineyards, resulting in the water in the vineyards being almost 40 centimeters high. This has several positive effects on the vines. On the one hand, the river brings numerous minerals and mud with it, thereby reducing the need for intensive fertilization. On the other hand, it washes out salts, which inevitably form due to irrigation and evaporation, and thus cleans the soil. Much of the water seeps into the ground and provides the plants with moisture for a long time, even when there is no rain.

These particular circumstances have not only ensured that wine has been grown here for centuries without the soil becoming drained, but also that the wines from Vergenoegd Löw have a very distinctive flavour. Connoisseurs worldwide appreciate the wines as top products from South Africa.

ARCHITECTURE

Built in the old Cape Dutch style, the architecture is reminiscent of the early days of South Africa’s Dutch settlement. Many of the buildings as well as the overall structure of the farm have retained much of their original character and reflect the last ‘untouched’ precinct of its kind in South Africa. Consequently, Vergenoegd Löw has been listed as one of the country’s highest ranked monuments worthy of preservation.

Vergenoegd and Cape Dutch architecture

The Vergenoegd Löw estate consists of a homestead with impressive 18th century gables, a farmyard, and several outbuildings, forming a so-called “werf”.

Cape Dutch architecture originated in the 17th century in the early days of the Cape Colony. The architectural style was introduced to the Cape by Dutch settlers and was influenced by German, French and even Indonesian elements. The most prominent features are the ornate gables, reminiscent of the elegant patrician houses of Amsterdam built at the same time. In the late 18th century, neoclassical Cape Dutch architecture was mixed with Georgian elements from British settlers, however only three houses in this style remain. The houses are usually H-shaped, with the front section of the house usually being flanked by two wings running perpendicular to it.

Many characteristics of the Cape Dutch architectural style are visible at Vergenoegd Löw: whitewashed walls, thatched roofing, large wooden sash cottage pane windows, and wooden shutters. The buildings have a rectangular structure, are usually single or double storey, and often have dormer windows.

At the turn of the century into the early 1900s the old Cape houses with their Dutch architecture were seen to be decidedly out of date with current fashions in Britain. People in the Cape wanted their houses to reflect the new Victorian trends. The dignified gables came down, thatch was replaced by corrugated iron, and the homely windows replaced by modern ones.

-

Liebbrandt, administrator of the Cape archives, was concerned by this modernisation trend and managed to convince influential people to preserve the beauty and charm of these houses by sketching, writing about, and photographing them. The Irish poet and artist Alys Fane Trotter (1828–1907) was soon seen peddling around the old houses of the Cape, sketch book in hand, whilst the South African writer Dorothea Ann Fairbridge (1862-1931) wrote about their architecture, and Arthur Elliot (1870-1938) shot photographs of the venerable buildings. It is thanks to records such as these, reflecting an enthusiasm for the hereditary Cape Dutch architecture, that magnificent homesteads such as Vergenoegd Löw have been maintained.

In Cape Town in particular, numerous old Cape Dutch buildings fell victim to the development into a modern city with a city centre characterised by high-rise buildings. The traditional Cape Dutch architecture can only be seen today in some of the farmhouses along the wine route, including Vergenoegd Löw as one of the finest examples, and in historical towns such as Stellenbosch.

One characteristic feature of South African colonial architecture is the extensive use of gables. Earlier research has repeatedly sought to justify the term ‘Cape Dutch’ solely by comparing the decorative form of these gables to those of Amsterdam. However, in the second half of the 18th century, the period in which the entire development of the South African gable tradition occurs, gable architecture had gradually ceased to be built in Amsterdam. North of Amsterdam, along the river Zaan, however, gable were still built at the time the Cape Colony was founded in South Africa.

South African gables have many features in common with gables along the river Zaan, in spite of the difference in the materials used. Yet, the Cape Dutch, or Afrikaner style, is clearly distinct from a local architectural renaissance, known as the ‘Cape Dutch Revival’ that gained popularity as a South African vernacular style during the mid-19th century. Unlike real Cape Dutch architecture, the Cape Dutch Revival style is defined almost exclusively by ornate gables. Nevertheless, the rise in popularity of the Cape Dutch Revival style led to a renewed interest in the original Cape Dutch architecture, and thus, many original Cape Dutch buildings were restored during this period.

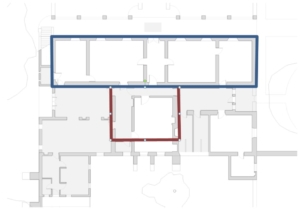

Vergenoegd Löw was not built as an estate in one fell swoop. It has evolved, been expanded, augmented, and changed repeatedly over the centuries. Only the front of the house, including the interior walls, seems hardly to have changed over the centuries. The rear of the house, on the other hand, has been changed and expanded again and again over 200 years and today appears asymmetrical and inconsistent

Because of the numerous changes, it is impossible to restore the house to its “original state” or to any particular period or style without losing certain elements. The walls from the 19th century or earlier are adorned with vernacular murals, which in themselves represent a unique scientific source. Some walls have been exposed and restored but many more lie hidden under the layers of paint that cover the walls.

The Homestead

Although the gable carries a date of 1773, it is unclear when the homestead or main house was built. The date could also be read as 1713, but this seems unlikely based on current architectural and historical knowledge, as the use of gables began later. Presumably, the gable may have been built on top of an already existing building at a later date. An examination of the gable from the inside of the ‘zolder’, a loft or attic, indicated that the so-called ‘holbol’ gables decorating the house had remained largely intact. The name ‘holbol’ gable is derived from the characteristic inward and outward symmetrical curves which are referred to as the concave hol (hollow) and convex bol (ball).

The front gable has never been altered. It was constructed from irregularly shaped homemade bricks and appears to only have been reworked at those points where roof beams were inserted. The front wall of the house, on which the lighter brick gable is built, is impressively wide at 60 centimetres. This level of intactness is extremely unusual, as many such old buildings were damaged by fire and environmental influences. The intact quality of the gable allows for speculation that even the plasterwork on the outside is original.

The ‘Voorhuis’

The front section of the house, the voorhuis, has the typical symmetrical shape with the holbol gable in the centre, and further gables on the sides. It consists of a central front room or voorkamer and a corridor from which rooms lead off to the right and left. The only deviation from the typical Cape Dutch architecture is the narrowing of the voorkamer to a kind of passage by moving the western side wall by half a meter. This is likely to have been an early alteration. The shape of the front gable is replicated on the eastern and western gables, with access to the zolder (attic) via a staircase on the western side. Its appearance is similar, if not identical, to the Brandes depiction. Although newer materials have been used since then, the voorhuis, with the exception of the window, has hardly changed since 1786. The window openings look the same as in the Brandes paintings, but the windows themselves were probably replaced in the middle of the 19th century.

The original structure of the front building had a simple rectangular shape, which has probably been preserved until today. A section of walling opened up for display purposes shows that the original core was built of crustal limestone and lime mortar, which clearly indicates that the gables, which are lightly built of homemade brick, were not placed on the stone walls until later. The innate weakness caused by the irregularly clad stones was compensated for by the construction of particularly thick walls. The older core of the house is characterised by a wall thickness ranging between 52 and 60 centimetres. The gables were built later, either in 1713 or, which seems more likely, in 1773.

The Rear T-Structure, ‘Agterkamer’

The rear part of the T-structure, the so-called agterkamer (back room), consists of a second reception area with a living room, a corridor, and what is now a kitchen area. These rooms share a common roof and a ceiling of broad yellowwood boards and possibly some additional pine boards. A second ceiling was later put in below the actual living room ceiling. The division of the rear T-structure into a corridor, a living room and the kitchen area dates to the time after 1806 when British influence began to pervade vernacular architecture. The presence of wall-paintings in the living room indicates that these changes took place during the early to mid-19th century. In the Brandes paintings, the kitchen was at the rear of the T-structure. Presumably this was demolished a long time ago and the area extended backward by a few metres. The lengthening of the agterkamer is visible in the walls of the zolder where a difference in the form and texture of the walling is noticeable.

The T-shape was probably created early on but is not part of the original building. The British period corridor leading through the house has unfortunately erased any archaeological evidence which could reveal whether the original walls were connected to the agterkamer. The change in elevation in the roof tends to indicate separate construction phases.

The Partial H-Form

In the late 18th or early 19th century, the building was altered from a T-shaped structure to a partial H-shape, which corresponded to the trend in local architecture at the time. These additions to the original T-shape are once again evident in the roof structure where there is a noticeable difference in the elevation of the agterkammer and the new wing. The construction of the arched roof over an external gap between the main house and the extension is as yet undated, but is believed to have taken place in the mid-19th century when the agterkammer was converted to a living room, kitchen and corridor. Presumable the back door of the agterkammer was bricked up at this time. It is also worth mentioning that the southernmost room of the extension shows signs of having had an opening in the ceiling which may have been used for an internal staircase.

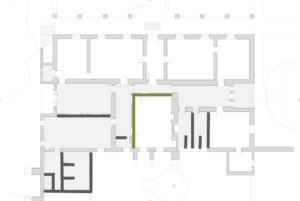

The ‘Afdak’ Kitchen

One of the Brandes paintings shows that no structures were built in this area in 1786 apart from a small lean-to. Subsequent photographs by Arthur Elliot in the late 19th century indicate a structure built up against the agterkammer in the form of an afdak, a flat-roofed shed-like annex. A 1987 sketch of the building by the architect John Rennie indicates distinct differences in the layout of the restaurant area as it is today. It shows that in this area of the house significant alterations have been made. Several internal walls were removed to create a restaurant area. During the alterations between 1987 and 2001, an open fireplace was installed, and the kitchen area extended into the rear werf. These alterations also involved re-roofing and new apertures. The work, which was done in keeping with the rest of the homestead, encompassed rebuilding from floor to ceiling. The only remaining wall was an earlier lean-to probably built in the 19th century which had been broken through in three areas before the last interventions. These openings were later bricked up and arches were built to connect the two sides of the dining room, conserving two wall cupboards in-situ in the process. This area is the most recent, and largest 20th century layer of the otherwise historical heritage site.

STRUCTURAL CONDITION AT TIME OF ACQUISITION AND MEASURES TAKEN

At the time of acquisition, the farm buildings were generally run-down and in need of extensive restoration. A structural engineer was engaged to examine the buildings and report on urgent, mid-term and long-term requirements, as well as commenting on the structural stability of the buildings.

Foundations

The buildings presumably do not have formal foundations, but were built over a thin layer of rock. This influenced the planning of necessary additions and, in places, required new foundations. This restoration work has been completed.

Walls

The walls consist of a mixture of stone, fired and unfired clay bricks, and soil. As is traditional for Cape Dutch buildings, the walls are finished in lime plaster and limewash, which is a breathable finish requiring annual maintenance. Because maintenance had previously been neglected, the walls were in need of restoration with loose and dilapidated plasterwork, as well as some surface cracking. Fortunately, the inspection of the homestead, barns, old slave quarters and cottage revealed that the cracks in the walls did not cause any significant structural problems but were repaired promptly to prevent further water penetration leading to deterioration of the walls. In the cellar, several cracks were found and repaired.

Roofs

The thatch roof of the homestead was in poor condition though it had received some patching and low-level maintenance in recent years. The timber structure supporting the thatch has large portions of the original wood, although damage caused by beetles needed to be repaired. On a section of the thatched roof above the agterkamer, the slope was less than the usual 45° due to material fatigue. The correct slope has been restored.

The roof of the old barn was in a critical state with large collapsed portions. The replacement of the entire roof was urgent to prevent further deterioration of the walls and floors which had been left exposed to the elements and had become green with moss and other signs of rot.

Many of the lintels over doors and windows were partly rotted, with signs of beetle infestation, and were repaired, augmented, and, where required, replaced.

The basement ceiling was in poor condition, requiring extensive restoration.

The slatted ceiling had to be replaced throughout the entire building. Since parts of the roof were covered with asbestos, which is a health hazard, special safety measures were required during the work. The asbestos has been removed.

Fire safety, plumbing and electrics

Extensive fire safety measures and compliance with modern hygiene standards were required. Major investment in the infrastructure was necessary for the wine estate to be run as a public tourist destination and professional wine business, including the modernisation of the heating, electrical, sewage and water systems. The fire protection concept had to be adapted accordingly.

To ensure the power supply, a solar system with an output of more than 50 kWh was installed on site. The estate is thus largely independent of the public power supply.

The existing wine cellars were considered too small for a winery aimed at the international market and were subsequently relocated to a new production building.

All measures to maintain and improve the structures have been completed. The work in the catering and hospitality areas is expected to be completed in 2021.

PRESENT USE

Vergenoegd Löw is now a popular destination for tourists as well as the local population. The winery has succeeded in reconnecting with the quality and reputation of bygone times.

Winery

During the planning and implementation of the extensive renovation and conservation measures, the viticulture was comprehensively analysed. The vineyards were enlarged, and the winery was completely renewed. In addition to the bottle warehouse, the storage capacity was increased to 150,000 litres.

New sales and distribution structures for Europe and Asia, in particular China, were created. The outward image of the winery was revamped. The name of the wine estate was augmented to give it a profile to the outside world which stands for quality and reliability: Under the brand name “Vergenoegd Löw”, the wine estate is now poised for a new chapter in its 300-year history. Based on the core values for the production and presentation of the wines, i.e., sustainability, cultural heritage, people, and award-winning wines, the estate faces a promising future that will continue to meet the needs of the ongoing conservation of this architectural jewel in the Western Cape.

Restaurants

Three dining areas were set up in the course of the renovations.

From September 2021, Clara’s Barn will offer upmarket cuisine in the main barn which had collapsed and has now been completely restored.

The Deli offers inexpensive delicacies at reasonable prices in the manor house garden, as well as providing sumptuous picnic baskets.

There are cosy gastronomic areas for wine tastings in the winery.

Hospitality

On the estate, accommodation has been created for overnight guests. A hotel complex was not built, but a decentralised strategy was pursued with autonomous small buildings that fit inconspicuously into the landscape. The accommodation offers views of the winery operations, environmental activities, the nature conservation zones with their rich flora and fauna, as well as the gastronomic facilities. The completion of the accommodation is planned for the end of 2021.

Guests

The winery is open to the public and various programmes afford guests an insight into viticulture as well as environmental protection activities. A separate sales area enables guests to purchase not only wines from the estate, but also other products at fair prices.

School classes regularly visit the estate since South African history cannot be experienced so closely anywhere else in the Cape.

Videos