„Without doubt, it belonged to the architectonically most precious lakeside estates of the Starnberg area. It could even be said that it is one of the most important villas of the greater Munich area.“

Gerhard Schober

Leading History Expert

Palais Sonnenhof is one of the most important architectural monuments on Lake Starnberg. Like no other, it reflects the zenith of bourgeois culture before the First World War, and, at the same time, represents the transformation of the lake area from an exclusive ducal refuge to a summer retreat for the increasingly self-confident bourgeoisie of the late monarchy.

Particularly after the First World War the villa became the scene of numerous political events. House searches by the revolutionary soldiers’ councils had to be tolerated, and battles with General Epp’s government troops took place here. The former ambassador of the German Reich, Count von Bernstorff, campaigned for the entry into the League of Nations. Starnberg’s surrender without resistance to the American troops was decided here. And from 1945 the American command of the US Forces was located here.

MORE | LESS

Palais Sonnenhof, originally known as Villa Böhler, was built in 1912 by Hans Noris, the protégé of the renowned architect Gabriel von Seidel, as a majestic and representative domicile for the art dealer and royal Bavarian court antiquarian Julius Böhler. In 1920 the villa was sold for the impressive sum of one million Reichsmark to the diplomat Johann Heinrich Graf von Bernstorff, who was, among other things, the ambassador of the German Reich in Constantinople. A year after Hitler came to power in 1933, von Bernstorff and his family went into exile and sold the villa to the son of the former mayor of Heidelberg, Ernst Walz, who was to become mayor of Heidelberg himself after the war. After Germany surrendered in 1945, the property became the regional headquarters of the American command office until the city of Starnberg acquired it in 1976 as part of an annuity agreement.

Today, the walls tell their version of a part of German history, an era of social unrest, governmental injustice and radical change.

With the acquisition of Palais Sonnenhof in 2002, The European Heritage Project took on the obligation to preserve for posterity not only one of the most important villa complexes of its time, but also an important symbol of regional heritage and cultural identification by restoring and renovating the buildings and grounds.

Its significance is evident even today in its presence in the Starnberg Lake Museum. A large, detailed model of the villa and its park, which documents the state of the property at the beginning of the 1920s, is one of the most prominent exhibits.

PURCHASE SITUATION

At the time of the acquisition by The European Heritage Project in 2002, Palais Sonnenhof had lost large parts of its structural fabric after decades of tolerated neglect by the city of Starnberg and the interventions of ruthless speculators. The property was on the verge of decay. Not only the villa, but above all the once stately park, were in a desolate condition.

Unfortunately, the time in which Palais Sonnenhof was under municipal administration was not without consequences. Merely 1.5 hectares of the original 6 hectare property remained. To the south, where once stood an outdoor swimming pool which was ahead of its time, an area of approximately 1 hectare was separated from the estate in order to build several social housing apartment buildings. The land and the greenhouses to the south-east on Hanfelder Straße, which were used as kitchen gardens and a nursery, were sold at a profit to a private gardening company. The largest area, consisting of more than 2 hectares, was allocated to the construction of the new Starnberg clinic. Finally, the city sectioned off the gatehouse and coach house and transferred them to a private individual, whereby the filleting was concluded.

Undecided about the future utilisation of the remainder of the estate, the city administration finally sold the remaining property including the villa to a group of dubious investors who allegedly wanted to build a sophisticated hotel on the site. After these plans failed due to a lack of liquidity, and an attempt at a facility for assisted living also failed, the property was to be divided into condominiums and sold. The required division permits were available and the monument protection authorities had already capitulated. But even for this the money was not enough.

Apart from occasional film shoots for which the property was used in the 1990s, the building now stood empty for years. The deep slumber commenced.

The acquisition by The European Heritage Project in 2002 led to the decisive change. The core property consisting of 1.5 hectares could be transferred in an arbitration between the quarrelling sellers.

To restore at least part of the original 6 hectare complex, the main outbuildings such as the gatehouse and the coach house were acquire from a private owner. To the north, additional green areas were purchased from the city, which enabled the reconstruction of the northern gardens on a somewhat smaller scale. To the south, a green belt could be added, so that the property again comprised 3 hectares after the acquisitions were accomplished.

REAL ESTATE FACTS & FIGURES

The listed villa is located in the southern Bavarian city of Starnberg, north of Lake Starnberg and west of the Leutstettener Moos landscape conservation area.

Palais Sonnenhof, originally known as Villa Böhler and later as Villa Bernstorff, was built in 1912 in the historic baroque style on the upper Hanfelder Berg. From the highest point it offers a panoramic view of the entire Alpine chain from Berchtesgaden to Lake Constance.

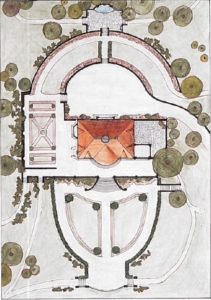

The central building consists of around 1,100 square meters of floor space over five storeys. Several outbuildings add another 350 square meters of floor space. The gatehouse and the former carriage house are located behind the entrance gate on Hanfelder Straße. Further north is a gardener’s house designed as a Nordic summer house. Immediately north of the central building is the driveway, which is around a central fountain, framed by a northern terrace wall and another central wall fountain.

The park originally covered an area of 6.4 hectares, of which about 3,1 hectares are still preserved. The park is also under preservation order today.

The terrain slopes downward from north to south, intersected by terracing. To the west, a beech forest covers the hills. While the style of the park is more English toward the north, the grounds to the west and south are more formal Italian in style.

Four fountains and three pavilions are spread across the property and are accessed by a comprehensive network of paths. In the extreme north-east and in the extreme south-west there are round wrought-iron pavilions, which are not only fixation points for deliberately created visual axes, but also allow different perspectives of the property, Lake Starnberg and the Alpine chain.

HISTORY

19th century: From fishing village to the summer retreat of the Munich bourgeoisie

Starnberg as it is today, grew together from two neighbouring settlements, which were characterised by very different economic branches. The old village of Achheim, south of the castle, was traditionally home to fishing; the north-eastern Nieder-Starnberg was home mainly to craftsmen and servants of the Munich court. However, when the Munich court preferred the castles in Berg and Possenhofen to the Starnberg castle for its events and magnificent festivities, the town lost its significance as the Wittelsbach summer residence.

But this did not last long. At the beginning of the 19th century, various Starnberg properties were transformed into small estates owned by nobles. Even wealthy middle-class families discovered the beauty of the landscape around Lake Würm, which was only renamed Lake Starnberg in the 20th century, and built villas as summer residences on the shores of the lake. Gradually some of the existing gaps around the lake were closed. There was, however, still no architectural unity. The development of Vogelanger and the southern Schlossberg commenced, while the first larger villas and palaces were built on Weilheimer Strasse.

From the middle of the 19th century onwards, Johann Ulrich Himbsel (1787 – 1860), who had already settled at Lake Würm in 1827, gave the actual impetus for the rapid development of the village of Starnberg by initiating steam ships on Lake Starnberg. Very early on Himbsel recognised the economic importance of combining a nearby city with unspoiled nature. In 1851, the saloon steamer “Maximilian”, built for 300 passengers, was launched in Starnberg and numerous Munich day-trippers who travelled through the Forstenried Park in coaches and carriages, enthusiastically accepted this new leisure attraction. To achieve a better utilisation of the boats, Himbsel began to extend the Munich-Starnberg railway line at his own expense. Benefitting from the railway line opened in 1854, the town experienced an unprecedented growth. The previously small community developed into the most important town on Lake Starnberg.

1912 – 1918: A masterpiece of representative architecture: between family idyll and art collection

In 1912, the important Munich antiques dealer and antiquarian to the Bavarian royal court, Julius Böhler (1860 – 1934), succeeded in acquiring one of the last highly attractive building sites on the upper Hanfelder Berg. The year 1912 also marked the beginning of a decisive turning point for Starnberg, when the town was awarded the “Classification of the rural community of Starnberg in the class of cities”.

Julius Böhler had already had a villa built in the so-called “Heimatstil” (domestic revival style) in Josef Fischhaber Strasse in Starnberg in 1900. This initial Villa Böhler still stands out today with its neo-renaissance façade with neo-gothic turrets and half-timbered buildings, but, after only a decade, the property no longer met the representative needs of the court antiquarian. After all, Böhler’s villa was intended to appropriately reflect his impressive bourgeois heritage.

Julius Böhler was born in 1860 as the eighth child of a family of craftsmen in the small town of Schmalenberg in the Black Forest. At the age of twenty, Böhler went to Munich and opened his first store in the city centre at Zweigstrasse. From this time on he specialised in paintings, sculptures and high-quality handicrafts. He opened a second art shop in Sophienstrasse shortly afterwards. At the age of 35, Julius Böhler was appointed “Royal Prussian Court Antiquarian” by Emperor Wilhelm II (1859 – 1941) as a result of his keen understanding of his art collecting clientele’s needs. At the turn of the century, Böhler’s career could only be described as “crowned with success”. Between 1902 and 1904, the “Palais Böhler” (today known as the Carolinen Palais) was built in the most central location on Munich’s Briennerstrasse, and the renowned architect Gabriel Seidl (1848 – 1913) was commissioned to design it. Just one year later, the meritorious art dealer was again appointed “Royal Court Antiquarian”, this time at the Bavarian court, under Luitpold, Prince Regent of Bavaria (1821 – 1912). In 1906, he entered into a partnership with his son Julius Wilhelm Böhler Jnr, initiating a generational change, and the head of the family gradually retired.

In 1912, Julius Böhler Jnr. commissioned Hans Noris, one of the most famous and progressive Munich architects of the time and a pupil of Gabriel von Seidl, to build an estate that would meet all the requirements of a luxurious country estate as well as express both the taste and lifestyle of the owner.

In 1914 the Palais Sonnenhof was completed.

1918 – 1934: Villa Böhler and politics

In 1918, post-war unrest led to the formation of the revolutionary Starnberg Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council. One of its first victims was Julius Böhler who was increasingly harassed. Even illegal searches of the property took place. In April 1919 skirmishes occurred between the Red Army soldiers and the government troops on Hanfelder Berg. Then the nightmare was over.

After Julius Böhler divorced his wife, she sold the entire estate in 1920 for 1,1 million Reichsmark to the diplomat Johann Heinrich Graf von Bernstorff (1862 – 1939). After the acquisition of the villa, von Bernstorff once again engaged the architect Hans Noris to make some structural changes. The most visible measure from the outside was the mirror-image and structurally identical addition of a second wing on the west side of the building.

The structural interventions increased the stately and representative appearance of the villa. In addition, more modern features were created during the conversion of the villa, such as the glass front of the conservatory that could be lowered into the ground, an unheard-of luxury for this time.

When von Bernstorff moved into Palais Sonnenhof, so did politics. Descended from a German-Danish family of diplomats who belonged to the ancient nobility of Mecklenburg, Bernstorff made quite a name for himself in the course of his political career as a conciliator and experienced strategic mediator. He held several positions in the diplomatic service of the German Reich, including posts in Belgrade, St. Petersburg, Munich, and from 1917 as ambassador in Constantinople. After the end of the war, von Bernstorff was offered the post of Foreign Minister which he rejected and subsequently resigned from the active Foreign Service. In an effort to devote himself to German domestic policy, he soon moved into the Reichstag for the liberal German Democratic Party (DDP – Deutsche Demokratische Partei) and retained his seat from 1921 to 1928. In 1922, he was appointed President of the German League for the League of Nations and campaigned vigorously for Germany’s entry into the international community. From 1926 he represented the German Reich as a permanent representative to the League of Nations. Many political decisions of national and international importance were made at Villa Bernstorff during this time.

1934 – 1945: Times of turmoil, from the Third Reich to zero hour

In view of the impending assumption of power by the National Socialists, von Bernstorff emigrated to Switzerland in 1933/34, in the course of which he sold the building in 1934 to Ernst Walz, the son of the former mayor of Heidelberg, Ernst Walz. The Walz family was not unaffected by the Nazi regime either. During the Weimar Republic, the lawyer Ernst Walz was head of the department for constitutional law, administrative organisation, municipal and savings bank supervision in the Ministry of the Interior and was appointed Ministerial Councillor in 1932. However, since Walz’s mother was an American of German-Jewish descent, he was forcibly transferred to the Court of Audit in 1935. Due to his background, he had to go into temporary retirement in 1937 and ultimately retire in 1942.

What exactly happened at Palais Sonnenhof between 1934 and 1945 during that dark period in German history can be speculated about, but some events are well documented.

One of these documented events was a ceremony in honour of the veterans of the First World War in 1935. The National Socialist War Victim’s Care (NSKOV) arose from the war victim support service founded after the First World War and took care of war-disabled front-line soldiers, the surviving dependents of the fallen, and the interests of former members of the armed forces in general. Its aim was to ensure that these people had a worthy place in society as “honorary citizens of the nation”. With this in mind, the NSKOV planned to build several settlement houses for the Starnberg district mainly reserved for this group of people. On 1 April 1935, the topping-out ceremony for the so-called “NS-Frontkämpfer- und Parteigenossen-Siedlung” (NS front fighter and party comrade settlement) was finally held on the grounds of the former Villa Bernstorff.

In the spring of 1945 the fate of Germany could no longer be averted; the downfall of the military was virtually assured, and strategic surrender seemed to be the only way to save the city of Starnberg from its demise, even if the deliberate betrayal of the fatherland or the endangerment of the “German resolve to fight” meant that resistance fighters were at risk of being sentenced to death.

The actual, highly dramatic decision not to surrender Starnberg to destruction, but to surrender without resistance to the advancing American troops, was taken at Palais Sonnenhof.

In 1949, the former mayor, Dr Hans Deuschl (1891 – 1953), revealed that a decisive meeting had taken place on 29 April in Villa Bernstorff between himself, Dr Max Irlinger (1913 – 1969), and the SS Commander in Chief. It was a meeting that was to have a decisive influence on the fate of Starnberg. District Administrator Irlinger, who belonged to the secret Starnberg resistance group, had issued an appeal to all mayors and gendarmerie posts in the Starnberg district on 27 April to forbid “the organisation of any resistance against the advancing Americans”. Only two days later, Irlinger was arrested by the SS for his appeal. Only thanks to the personal intervention of the mayor, Hans Deuschl, an SS leader himself, that Irlinger was kept alive. In the memorable meeting on 29 April, the three gentlemen, including the two SS representatives, decided against any further senseless defence of Starnberg. The SS troops withdrew. Starnberg thus escaped a catastrophe. There was no resistance against the Americans.

On the afternoon of the following day, the first American tanks rolled in on Hanfelder Street.

1945 to 2002: Large-scale plans and film shootings

After the end of the war, Palais Sonnenhof was converted into the local headquarters of the US Forces. The US military thus took control of Palais Sonnenhof. In 1948 the commandant’s office was dissolved again.

In the same year, Alfred Walz transferred Palais Sonnenhof to his daughter, Edith. Due to financial difficulties, the daughter and her husband made a lifetime annuity agreement with the city of Starnberg in the 1960s, which guaranteed both of them a monthly payment until their deaths. At the time of the death of the remaining spouse in 1976, the entire property was transferred to the city of Starnberg. A social housing complex and the Starnberg hospital were built on the southern parts of the estate. Parts of the park grounds were sold. Finally, the city sold the core of the property, including the villa, to a dubious group of companies that had submitted plans to build a hotel. However, due to internal discrepancies and a lack of funding, the numerous projects were never implemented.

As a result the building stood empty and was only been used occasionally for events and film shoots. In 1996, under the direction of Rainer Kaufmann (*1959), the villa became the main filming location for the German feature film “Die Apothekerin”. The film, based on the novel of the same name by Ingrid Noll (*1935), played a decisive role in the success of the so-called New German Cinema in the 1990s.

Due to the increasing financial difficulties of the group of companies owning the property, the financing banks had announced the recovery of the investment. As a result, one of the parties had transferred the entire property to a fictitious entity for DM 10, against which an objection in the land register had been obtained from his partner. The public prosecutor’s office was investigating breach of trust and various property crimes. Through intensive mediation, The European Heritage Project was able to resolve this complicated situation in 2002 and acquire the property.

ARCHITECTURE

The Villa

Palais Sonnenhof, as the Villa Böhler built in 1912 is called today, cannot be clearly classified stylistically. In its structural design, the villa, designed by Noris, combines several styles. Outside, for example, there are both Baroque and Classicist features, while the interior of the villa features Renaissance, Mannerism and Rococo styles. In 1912, of course, these styles belonged to bygone epochs, but the adaptation of the erstwhile contemporary Art Nouveau style and modern construction methods and techniques, such as the use of solid reinforced concrete in structural statics, indicate an eclectic style.

Villas built by the architect Hans Noris in Munich and the surrounding area are mostly classified as Art Nouveau, but this stylistic classification is simply not possible for this property. Palais Sonnenhof does however have elements corresponding to Art Nouveau, such as the tiles in the sanitary facilities, the sculptural representations on the facades and terraces, and the linear hipped roof characterised by a certain lightness, appearing less austere than is the case with classicist construction methods. All in all, various epochs merge in the sophisticated property.

Eclecticism can be used as a demarcation from historicism to better classify the stylistic pluralism widespread at that time. Palais Sonnenhof offers an excellent example of eclectic architecture. One must bear in mind the basic intention of the initial owner. The structure was to reflect Julius Böhler’s attitude towards life. He had based his existence and prosperity on trading in cultural artefacts from various historical eras. In the design of the house, he not only wanted to display his respect for all epochs of the past, but also to express that the present only makes sense through the achievements of the past.

In terms of its cubature, the building itself is designed as a baroque complex. Side wings adjoin the semi-circular central building, which are, however, lower than the central building with only two storeys. The representative windows on the ground floor are designed as semi-circular ensembles based on Palladio, and provide a view over the symmetrically structured gardens towards Lake Starnberg along a terrace stretching the entire length of the building.

It can be said that the way in which Noris designed and built Villa Böhler was significantly more progressive than that of most of his contemporaries, who were also committed to historicism. Besides Noris’ design of the property, the use of the most advanced building techniques is particularly noteworthy. For example the extensive use of reinforced concrete in the construction of the building is almost extraordinary, since the walls, most of which are not load-bearing, are double walls made of ordinary masonry but reinforced by an additional layer of concrete. Walls of this thickness are rarely found in ordinary houses built at that time and far exceed the static needs of the villa.

A further example of Noris’ unconventional use of new technical resources is the glass front in the villa’s conservatory, which can be completely lowered into the ground. This versatile glass wall on the one hand removes the boundaries between the house and the garden and on the other represents an absolute novelty in engineering at the time. Comparable elements may be found in much later architectural masterpieces of modernism, such as the Villa Tugendhaft in Brno, Czech Republic, built between 1929 and 1930 by the famous architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886 – 1969) and is today considered one of the “crown jewels” of modernism.

Noris’ playful eclecticism, of course, contrasts starkly with the minimalism of architectural modernism later on and is therefore not stylistically comparable. Nevertheless, the fact that this eclecticism, so wonderfully represented in Palais Sonnenhof, would essentially influence a later architectural movement, should not be underestimated: Postmodernism, popular from the 1960s onwards, with its motto “anything goes”.

Palais Sonnenhof creates an impression of balanced serenity thanks to its symmetrical façades and beautiful hipped roof. By using down-to-earth materials and high-quality, detail-focused workmanship, the façades make an impression without any accessories, simply by virtue of the quality of the architecture. The villa was designed to make an impression from all sides and, unlike older houses on the lake, many of which only have one side to present, all four façades are equally impressive.

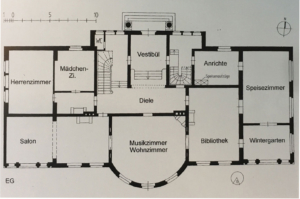

The interior layout of the building can be seen very clearly from the south-facing garden façade. The ground floor, characterised by French arched windows, contains living and reception rooms. The main entrance to the villa is located at the back of the building and is flanked by columns. Above this, there is a belvedere, a type of raised patio which overlooks the entire rear park. From a vaulted vestibule equipped with red marble staircases, visitors reach the generously dimensioned, light-filled living rooms. The large music room, whose exedra-like window side gives the room a special touch, occupies the centre. The niche-like space of this so-called exedra as an interior design element was very popular in antiquity, as a design feature for living rooms intended as a separate space for smaller groups. It was rediscovered in modern times in Europe as a part of secular architecture, especially in the Renaissance and Baroque when the exedra was used again.

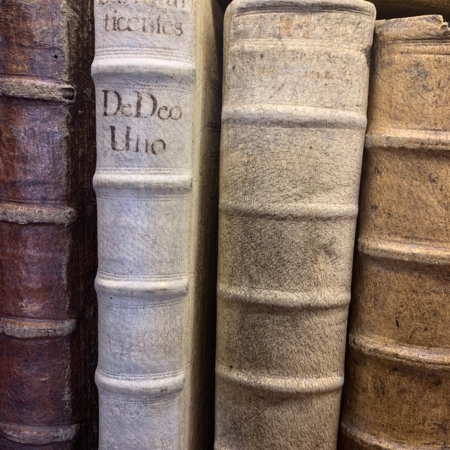

Located next to the music room are a salon and a library with 17th century Florentine wooden coffered ceilings, imposing marble fireplaces also originating in 16th and 17th century Italy, as well as red marble door frames which Böhler had obviously succeeded in extracting from a Florentine palazzo. The dining room, with an elevator to the kitchen below, has been located behind the winter garden since the renovation by Count Bernstorff. A special feature is the aforementioned window of the conservatory which can be lowered into the ground.

Overall, the spatial concept of the representative ground floor is to reflect the various artistic epochs of European history. From Gothic-Renaissance furnishings in the library, and Mannerist elements in the salon, to Baroque elements in the music room, and Rococo stucco in the study, each room is designed as a separate ensemble of an era.

On the upper floors, there are several bedrooms and bathrooms. The more simply designed first storey is rounded off on both sides by large balconies.

The park

The expansive park, designed according to the English garden form of informal landscape, stretches from the top of the hill down to Oswald Street. It forms a long, trapezoidal area which drops significantly to the south and offers an unhindered view of the entire landscape. While the area on the eastern side drops down to Hanfelder Street, it rises steeply on the western side culminating in a vantage point with a pavilion on a hill southwest of the villa. This not only results in an effective graduation, but also a varied system of paths. Visitors can step down from the elevated villa terrace via an expansive staircase into the garden in front of the lake-facing façade which is laid out as a baroque-style parterre. At its apex the garden parterre is bordered by another pavilion which is designed as a tea house, behind which an arched balustrade with baroque ornamental lattice separates the plateau area from the sloping terrain. From here walkways on both sides lead to the lower part of the park. At the back of the villa, a similar layout in a wide arc, reflects the front garden parterre. This is the destination of the driveway which is bordered by a slightly elevated and easily accessible rampart, backed to the north by two graduated tuff stone walls. In the middle, stairs lead to an area formed by tuff walls with benches and a fountain. From this area, walkways lead to the back of the park. The rear garden parterre also reflects the strict order of a baroque complex.

To the west of the villa, there is a rectangular ornamental garden, decorated by a wall fountain. The strictly geometrical parts of the garden at the villa form terraced areas within the elongated slope. This effectively emphasises the building and promotes its prominence. From the ornamental garden, a narrow path leads up to a vantage point on a hill with an open pavilion, from where a shaded walkway through a wooded area leads to the back of the park.

Outbuildings

Palais Sonnenhof comprises numerous outbuildings that were only reintegrated into the property after 2002. There is a gatehouse and a gardener’s house as well as the former stable and the carriage shed behind the entrance gate on Hanfelder Street. These outbuildings are on the same level as Hanfelder Street, while the villa is a few meters higher, and can hardly be seen from the villa. Stylistically, they reflect the main building in summarized presentation.

STRUCTURAL CONDITION AT TIME OF ACQUISITION

Since Palais Sonnenhof stood largely vacant since the 1970s and was only sporadically rented out for filming, no maintenance of the buildings or the grounds took place for more than three decades. As a result, the water pipes and power lines were in a dilapidated state and electrical and heating systems did not meet current technical or energy standards. Furthermore, the foundations and cellars were eroded by permanent exposure to rain and displayed considerable water damage. The roof structure was also weather-damaged and had partially rotted due to the leaking hipped roof. A large part of the façade was overgrown like Sleeping Beauty’s castle. The interior also suffered considerable damage and the entire exterior façade crumbled. The entire park was in an unrecognisable condition.

There was nothing left of the historical furnishings of the estate. Only permanently installed fixtures were spared from the apparently systematic looting.

RESTORATION AND CONSERVATION MEASURES

After the acquisition by The European Heritage Project in 2002, an extensive restoration and refurbishment of the entire estate took place. In 2005 the work on the main building was completed. After a three year process of revitalisation, the restoration of the sophisticated garden landscape was successfully completed in in 2006.

In close cooperation with architects, engineers, restorers, landscape architects and the Bavarian Heritage Society, the eclectic historic estate, which is an important visual testimony to the eventful history of Starnberg, was restored to its former glory.

It was essential to consciously combine various styles down to the smallest detail, especially regarding interior design. As a homage to bygone art historical epochs, each individual room on the ground floor was attributed to an era, and restored and decorated as such, according to the plans of the first owner Julius Böhler and the architect Hans Noris. Today the various rooms reflect the various styles.

Statics

Due to the hillside location of the villa, the foundation and basement of the building were permanently eroded by rainwater, resulting in large quantities of underground water that could not drain off. The stability of the entire building was therefore permanently threatened. The moisture rising from the underground area of the house threatened to cause more damage to the entire property, especially to interior design elements such as wooden ceilings, panelling and floors.

The foundations had to be excavated to a depth of 6 meters and re-walled. Drainage facilities had to be built for the water coming down from the slope. Defective elements of the foundations were replaced. Horizontal barriers against rising damp were installed in the walls.

Roof and truss

The leaking hipped roof, with varying roof pitches, several dormer windows, and a closed bay window, had to be completely renewed except for the sheet metal construction at the edge of the roof, and all the slate panels had to be replaced. The beams of the roof truss were severely damaged by water penetrating from the outside. As a result of the dampness, the rotten beams in the entire truss had to be dried and repaired and, in some cases, completely replaced.

Heating, electrics and plumbing

The electrics, heating, water pipes and power lines were in a thoroughly dilapidated condition as they had not been renovated since the building was erected in 1912 and expanded in 1920. The entire electrical and water supply systems had to be completely upgraded and re-installed. The archaic heating system was replaced, and the decorative, cast-iron radiators retained and reinstalled after restoration.

Reconstruction

Floors

In the entrance area, the original stone flooring was retained as far as possible, damaged slabs were restored, and missing ones added. The softwood parquet floors with hardwood edgings in the ground floor rooms, with varying patterns depending on the room, were preserved thanks to extensive maintenance including sanding, polishing and sealing. The orange and white Art Nouveau tiles on the terraces and balconies were straightened, restored and, where necessary, supplemented by accurate replicas.

Doors and windows

The arched French box windows were retained in their original form and simply re-sealed. The original wooden and red marble doorframes were fully restored without loss of substance.

Park

At the time of the acquisition by The European Heritage Project, the grounds were completely overgrown and wild, and required the most attention in terms of time. The once stately park, based on English design principles, was barely recognisable and far from its original state.

Initially, parts of the land in the northern and southern parts of the grounds which had previously been sold by the city of Starnberg were bought back. All cascades, gravel and cobblestone paths were expertly renewed, and the walkways reconstructed according to the original model. The numerous pavilions and fountains were extensively restored. The ornamental gardens were newly laid out.

Masonry

The oversized wall thicknesses are particularly impressive, even in the non-loadbearing walls. This type of construction can be found in bunker construction but is rather unusual in ordinary residential construction. But even such a structure is not entirely impervious to the effects of weather and time. In particular, the external walls had to be sealed in many places with filling material. The entire plaster was renewed with historical materials in consultation with the monument protection authorities.

The decorative masonry found in many areas of the park also required extensive restoration. Since this is volcanic tuff stone, which is particularly susceptible to erosion due to its natural porosity, severe weather damage had to be removed. The majority of the walls, which serve the purpose of landscape architecture, had to be straightened, cleaned and individual blocks of tufa stone replaced with the appropriate local material.

Restorations (art & craft, stucco, frescoes etc.)

The focus of the restoration of Palais Sonnenhof was not to convert the building for contemporary use, but above all to restore it in accordance with its historical function. It was therefore logical to restore by hand the valuable artefacts such as ornamental elements and historical furnishings. The preservation of the richly detailed and extremely precious 16th century Florentine coffered ceilings in the salon and library posed a unique challenge. The ceiling panels had to be removed, reworked and reinserted individually. Additional coloured ornaments, such as individual decorative wooden rosettes, were restored according to old manufacturing techniques using original recipes for paints, varnishes and oils.

Individual Italian marble elements from the 16th and 17th centuries, such as decorative columns, fireplaces and doorframes, were expertly restored. Decades of untreated acid damage had resulted in chemical burns and considerable dulling of the originally shiny surfaces. In some places, the stone had completely broken off. All marble elements were cleaned, polished, sanded, touched up, repaired and then impregnated.

The empty tea room in the west wing of the ground floor was completely refurbished. The pastel-coloured to lemon-yellow opulence of the room was emphasized in cooperation with restorers, plasterers and antiquarians by means of new stucco, original overdoors, historic wall panelling, as well as original rococo mirrors, chandeliers and furniture.

PRESENT USE & FUTURE PLANS

With its picturesque and, by Starnberg standards, rather quiet and secluded hillside location, the proximity to Lake Starnberg, and a magnificent mountain panorama, Palais Sonnenhof, together with its impressive building and landscape architecture, is an extraordinary testimony to the luxurious lifestyle of the Munich bourgeoisie at the beginning of the 20th century.

Today, the estate is used primarily for residential purposes, but also for regular concerts and diverse cultural events. Thanks to the generous outdoor area, the magnificent terraces and the expansive park, Palais Sonnenhof offers, especially in good weather, an incomparable potential for numerous events, surrounded by a stately and unforgettable atmosphere.