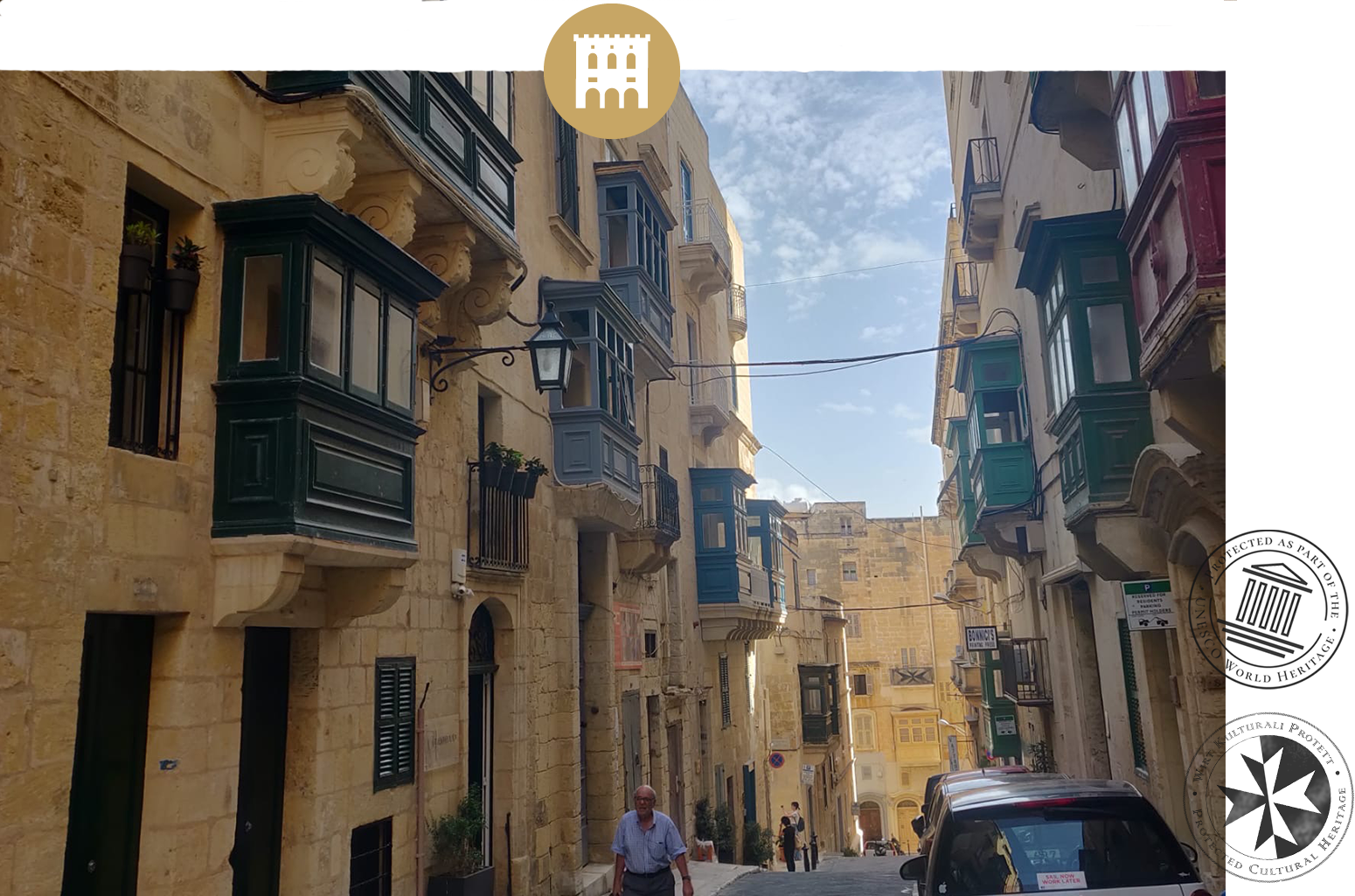

Valletta itself is an architectural masterpiece. Surrounded by the towering and majestic fortifications built by the Order of the Knights of Saint John, it is a treasure trove of architectural beauty.

(Valletta, European Capital of Culture 2018)

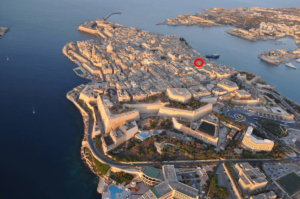

In 2014 The European Heritage Project acquired one of the most original, small chivalric palaces in Valletta, a prime example of the unmistakable, knightly limestone architecture of the city. Located in close proximity to the Upper Barrakka Gardens and St. John’s Co-Cathedral, the palace overlooks the Three Cities and the Grand Harbour.

Originally built in the early 17th century during Valletta’s golden age under the Order of St. John (later known as the Order of Malta) and expanded in 1699, the building blends seamlessly into the city’s checkerboard pattern, a revolutionary urban planning concept ahead of its time.

Since 1980 the city of Valletta is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

PURCHASE SITUATION

Originally a single building complex, it was acquired by The European Heritage Project in two stages in 2014 and 2016. During the socialist regime in the 1970s and 80s, after several changes of ownership, the building was expropriated and divided into condominiums. To enlarge the floor area and living space, intermediate ceilings were installed in the large historic rooms in the course of remodelling, creating additional living spaces with a ceiling height of less than 2 meters, in some cases even less than 1.70 meters. Since the construction of new, more modern housing outside of Valletta from the 1990s onwards, the property was gradually abandoned by its residents and has been virtually unoccupied since the early 2000s. In 2014, The European Heritage Project signed purchase agreements with the owners of the vacant residential properties. By 2016, the remaining condominium owners also sold and moved into a modernised building. This allowed the restoration of the historical unity of the complex.

HISTORY

After the island of Malta was granted to the Order of St. John (also known as the Knights Hospitaller) by the Spanish Emperor Charles V in 1530, Malta was the area of influence of the Order of St. John, which later evolved into the sovereign Maltese Order of Knights, who found their retreat here after the exodus from Palestine (1291) and Rhodes (1522). After the Turkish siege troops were successfully driven back by the Knights of the Order in 1566, their Grand Master Jean Parisot de la Valette (1494-1568) decided to reconstruct the demolished fortress of St. Elmo and also build a completely new fortress city in the western extension of the peninsula, today’s Valletta. Financial support was promised by the Spanish King Phillip II (1527-1598), but above all, Pope Pius V (1504-15729) who also dispatched his best military engineer Francesco Laparelli (1521-1570) to Malta to realise the project. The city was designed as the most modern in the world, both from a military strategic and representative point of view. Logistics, infrastructure, water supply and the entire disposal system followed a very sophisticated concept. The chessboard-like road layout was designed with the supply of fresh air in mind. After Laparelli left the island in 1568, his assistant Gerolarmo Cassar continued the work.

During this period, the palazzino in the Strada Pia, today Melita Street, was also built. The Strada Pia connected the eastern and western parts of the peninsula and was named after Pope Pius V as an acknowledgement of his support. The palazzino itself was located near the St. Peter and St. Paul Bastion to the southwest and thus also near the land access to Valletta. The Lower Barrakka Gardens, established as a recreational area for the Knights of the Order in 1661, were only a few steps away. The palazzino offered a strategic view of the big harbour, Fort San Angelo and the southern sea passages.

In 1798 the Order capitulated to the Napoleonic fleet and was dissolved. The Strada Pia was renamed Rue de la Félicité Publique in accordance with revolutionary doctrine. After the French interregnum ended two years later, the street received the popular name Strada del Gran Falconiere, indicating the falcon breeding that took place there.

As a result of the 1814 Treaty of Paris, Malta became an English crown colony. During an anglicisation campaign after the First World War, the street was renamed Britannia Street in 1927. It was not until after Malta gained independence in 1964 that it was given its present name Melita Street, alluding to the Bronze Age site of Melite, which is a relic under the central city of Mdina. The entire historic old town of Valletta has been on the UNESCO World Heritage List since 1980. In 2018 Valletta was named European Capital of Culture.

ARCHITECTURE

The building complex was designed by the city architect Francesco Laparelli (1521-1570), but was not actually built until 1583 under Gerolarmo Cassar (1520-1592). In the middle of the 17th century, Pierre de Roussillon, Knight of the Order of Saint John, acquired the property as a representative residence and added an additional storey as well as other extensions. Today, the palazzino consists of three storeys, a surface area of 520 square meters, and a total area of approximately 1.150 square meters.

The building complex is located on the southwestern slope of the peninsula. Like most of the buildings in the old town, it is built from the typical light brown and relatively soft sand-limestone bricks, the raw materials for which are mined in the southwest of Malta. The building ensemble essentially consists of three parts grouped around a shared inner courtyard.

The representation rooms, with ceiling heights of up to 5 meters, are located in the building on the street side. The reception hall and the library are on the ground floor and the knights’ hall is located on the first floor. In the rear building, the ground floor houses functional rooms. The bedrooms are distributed over three storeys above these functional rooms. From its roof terrace, the fourth floor provides an expansive view over the sea to Fort San Angelo.

The courtyard illuminates and ventilates the adjoining buildings and allows the vertical transport of heavy goods via a cable device. Numerous vaults and arches enhance the overall appearance in the courtyard and entrance area. In addition to the impressive staircase, the spiral staircase carved from solid stone connecting all floors and the cellars is remarkable.

The entire property has a large basement with vaulted ceilings. The ingenious architecture of the building ensures that even the basement rooms are adequately ventilated. There are multi-storey cisterns cut into the rock beneath the entire ensemble. Even today, a large part of the water supply is provided via these underground tunnels.

The street façade was intentionally kept simple. As is typical for the country, numerous exterior balconies and oriels, so-called “gallariji”, were added. The gallariji, as well as the other wooden elements painted emerald green, such as doors and window frames, traditionally form a radiant contrast to the light matte sand-limestone of the façade.

RESTORATION

The entire complex had been vacant for many years. The flat roof structures failed to withstand the winter rains and had partially collapsed. For decades, no repairs or maintenance work had been carried out on the buildings. Pipes were rusted through due to non-running water. The façade of the building tilted dangerously outward. Some of the vaults and struts in the cellar were cracked. The fact that the building had been vacant was not the only problem. Problems arose due to the division of the complex into nine separate condominiums. This reallocation resulted in numerous significant changes to the structure of the buildings, the most serious of which was the installation of additional ceilings which horizontally divided the large halls of the historical structure. The sub-division also resulted in numerous partitions being added and sanitary facilities arbitrarily incorporated into the existing structure. In addition, most of the measures were executed without sufficient static safeguarding, posing a risk of collapse in some areas of the building. In some parts, the historical windows had been replaced by simple plastic windows.

The initial restoration work focused on the structural and static safeguarding of the building. Where possible, leaks in the roof had to be repaired where possible. The parts of the roof construction which had collapsed, including the entire load-bearing wooden beams, had to be reconstructed. Installations that threatened the static stability of the buildings had to be removed. The cistern system caused unexpected effort. Its function was significantly diminished due to numerous constructional interventions. The entire system had to be reinforced and partially rebuilt over two subterranean levels. The dangerous tilting of the street-side façade was counteracted by anchoring. In the cellar, numerous cracks in the vaults were repaired and filled, and some struts had to be rebuilt. The limestone façade had to be cleaned.

During the second phase, the subdivision constructions were carefully dismantled. In particular, the removal of the modern ceiling structures in the large representation rooms had an impact.

The third phase focused on restoring the originally intended use of the buildings. All stone structures were expertly restored and, where missing, reconstructed. Windows and doors were restored and, where necessary, replaced, and fittings reworked or replaced. All exterior balconies and bay windows, the traditional “gallariji”, were completely overhauled. All rooms were reallocated according to their historic function. The power and water supply systems were modernised.

A modern glass elevator was installed in the inner courtyard to make the individual storeys barrier-free. In addition, a floating staircase on the upper floors now leads to the roof terrace.