The unusual combination of late Gothic architectural elements and remnants of Viking-age settlements, combined with its location on one of the northernmost Shetland Islands within a UNESCO Global Geopark, makes Brough Lodge a globally unique ensemble.

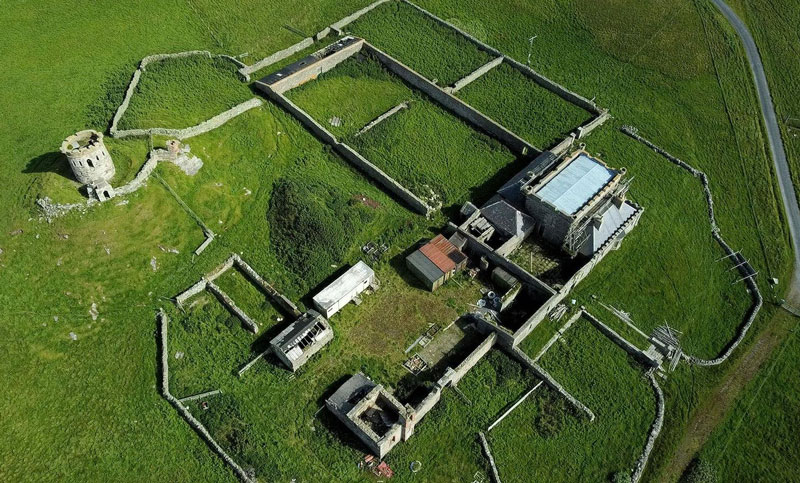

Located on Fetlar, one of the northernmost Shetland Islands, surrounded by the dramatic coastline of the North Atlantic, the Brough Lodge sits atop a small hill amidst rugged terrain. It is predominantly a decaying castle complex from the early 19th century, constructed in the neo-Gothic style atop the ruins of an Iron Age Viking settlement from a much earlier period.

Brough Lodge is not only one of the northernmost examples of courtly architecture in Northern Europe but also a significant center for medieval and even Iron Age activities along the Viking routes. Fetlar has a wealth of prehistoric evidence, with Viking settlement dating back to the 8th/9th century. Its strategic location, as one of the northernmost European islands, made it an ideal base for seafaring warriors who sailed from there in their famous longships, venturing into the most remote areas.

Much later, in 1825, Sir Arthur Nicholson, a successful and respected merchant and landowner, decided to build Brough Lodge on this historically rich ground. In 1806, he acquired the associated lands by settling a debt with the then-owner of the lands, Andrew Bruce of Urie. After the acquisition, Sir Arthur Nicolson initially occupied his house, known as the “Haa von Urie,” before deciding to construct his life’s work, Brough Lodge.

Despite the immense significance of this complex, there are practically no actual records of the construction phase. It is known that around 1800, Sir Arthur Nicolson traveled throughout Europe for his business ventures and drew architectural inspiration from his travels. In any case, the composition of Brough Lodge exhibits typical neo-Gothic design elements from France, Switzerland, and Italy.

MORE | LESS

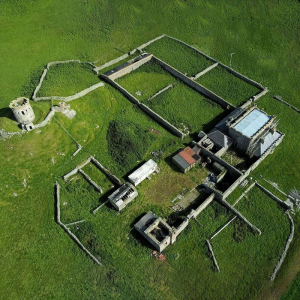

Brough Lodge embodies not only this somewhat atypical neo-Gothic style for the far north but also a variety of other expressions in the scattered neo-medieval buildings and structures, including a closed courtyard, a walled garden, and an on-site chapel. Of particular historical importance is the tower, which was used as an observatory during Nicholson’s time. Built on the Iron Age remnants of a so-called “Broch,” it bridges the gap between the past and the present. A Broch was a tall stone structure typical in Scotland, especially during the Iron Age, which lasted from around 400 BC to the first century AD. The surrounding Viking-era buildings are now only recognizable as fragments awaiting further scientific classification.

The unusual combination of late Gothic architecture and Viking-age settlement remnants on one of the northernmost Shetland Islands makes Brough Lodge a globally unique ensemble.

The fact that this lodge is also located within a UNESCO Global Geopark only underscores this uniqueness.

The high significance of this complex was confirmed by heritage conservation authorities, who classified Brough Lodge as a Class A monument, the highest level of protection.

In mid-2023, the European Heritage Project was able to acquire the ensemble from the nonprofit Brough Lodge Foundation for a symbolic purchase price. From the perspective of the European Heritage Project, the restoration and revival of this significant castle complex aim to contribute to a better understanding of life at the northernmost edges of Europe and make this unique monument accessible to a wide audience.

PURCHASE SITUATION

Since 1970, the Brough Lodge has been effectively uninhabited and, since 1998, it has been managed by the Brough Lodge Foundation. This foundation was established by locals and descendants of the Nicolson family with the goal of saving Brough Lodge. The foundation has tirelessly worked towards preserving the site and, over the years, managed to raise over half a million pounds, which were used for necessary restoration work.

However, it became evident that saving Brough Lodge was a race against time. The deterioration was accelerating and seemed nearly unstoppable. Various options for restoring the building were explored, and eventually, the conviction grew that only an organization with a genuine interest in this historical relic, specific expertise in heritage conservation, and the financial resources needed to undertake such a monumental project to save it.

Subsequently, the Lodge was put up for sale at a symbolic price along with a concept for its planned revival. This approach garnered worldwide media attention, and the European Heritage Project was eventually approached regarding this unique property in the far north.

During the tendering process, numerous international parties were evaluated, and their proposals were compared. The Trust’s expressed goal was to find a philanthropic organization with a true vision and profound knowledge, one that was deemed capable of handling this project both professionally and financially. Among other things, the revival plan developed by the foundation for Brough Lodge included a gentle hotel use, with the aim of revitalizing Fetlar’s economy and culture, in addition to restoration efforts. The European Heritage Project evidently met these criteria. Over the years, they have successfully rescued numerous architectural and cultural monuments from decay and have also implemented sustainable usage concepts, including several hotels, restaurants, and agricultural ventures within these heritage sites.

In the summer of 2023, the European Heritage Project finally signed the purchase contract, committing to the upcoming restoration efforts associated with this project.

PROPERTY FACTS & FIGURES

The island of Fetlar, where Brough Lodge is located, is one of the northernmost islands in the Shetlands and is often referred to as the “Garden of the Shetland Islands” due to its lush greenery. The name Fetlar comes from Old Norse and roughly translates to “the island of fertile land.”

Fetlar is one of the smaller Shetland Islands, covering an area of 40.78 square kilometers (15.75 square miles). At the same time, it is one of the least densely populated islands in the group, with only 61 residents as of now. This low population can be attributed partly to its remote geographical location; reaching Fetlar from the Shetland Mainland requires at least two ferry crossings. The underpopulation is also a result of the “Highland Clearances,” a period of depopulation of rural areas in northwest Scotland (see: History).

Fetlar is home to numerous bird species, particularly in the northern part of the island, which is designated as a bird sanctuary. It is a true paradise for ornithologists.

The island boasts various archaeological sites from ancient times. In the center of the island, you can find Haltadans, a Celtic-Neolithic stone circle. Among many other sites, you can also admire the remains of a Viking-age longboat.

Fetlar has a thriving community life. The predominant craft is knitting, which is celebrated and passed down from generation to generation.

Brough Lodge is the most renowned complex on Fetlar and is situated on the western side of the island, perched on a hill, offering breathtaking views over Colgrave Sound to the west and inland to the east. Conversely, the Lodge and its ancillary buildings form a distinctive landmark that is easily visible from afar.

The Brough Lodge property spans 40 hectares (approximately 99 acres) and includes its own peninsula with two expansive sandy beaches and a private boat dock.

HISTORY

The Shetland Islands have been inhabited since the 3rd millennium BC. As Fetlar is practically devoid of trees, Neolithic cultures had to rely exclusively on stone for their dwellings. Therefore, Shetland is rich in stone relics from the prehistoric era, with over 5,000 archaeological sites in total.

One of these sites is Haltadans in the center of the island, a stone circle dating back to the early Bronze Age consisting of 38 stones with a total diameter of 11 meters and two distinctive central stones. Local legends surround this place; see below for ” Things to know & Curiosities”.

In the later Iron Age, it was mainly the so-called “brochs,” round stone towers, that were built throughout Shetland, and remnants of these can still be found in some places. On the grounds of Brough Lodge, there are clear indications of settlement during the Iron Age, as the remains of a broch on which the later observation tower was built are verified archaeological monuments.

During the 9th and 10th centuries, the Vikings settled on Fetlar, shaping its history and culture. For over 300 years, the Vikings were the most experienced sailors in Nordic waters. Their high-quality boats were capable of undertaking the often treacherous journeys to new lands. Fetlar’s strategic location made it an ideal outpost for these seafaring warriors who voyaged in their famous longships across the surrounding seas.

However, the Vikings were not just conquerors but also settlers and farmers in the Shetland coasts. They adapted to the Shetland’s landscape, which significantly differed from their original settlements. Due to the absence of forests, trees, and therefore wood, which was the primary building material for the wooden longhouses prevalent in Scandinavia, they used what was available, namely stone. Since stone hardly deteriorates over time, many of the stone longhouses they built have survived. Before the Viking Age, the native Shetlanders had constructed roundhouses, relics of which are also preserved.

The Vikings not only changed the architecture but also had a fundamental influence on the culture and life in the Shetland Islands. They determined how land was cultivated and society was governed. Their boat-building and seafaring skills opened new horizons for fishing and trade. Much of what one sees on the Shetland Islands today has been strongly influenced by these Nordic settlers.

Towards the end of the 10th century, the Vikings, who were known more as wild barbarians, were Christianized.

It was Viking King Harald Bluetooth who recognized that Christians would only trade with their fellow believers, and like other European rulers of the early Middle Ages, he realized that with the help of the church, he could secure and expand his power. Shortly thereafter, the Viking age ended, and around 1195, Shetland came under direct Norwegian rule, which lasted for over two centuries. In 1469, the islands came under Scottish control.

In the 19th century, Fetlar experienced a tragic turning point in its history – the so-called “Highland Clearances.” This term mainly refers to the eviction of the indigenous population from their ancestral lands to make more room for livestock, especially sheep farming. At the same time, the Industrial Revolution led to a migration to production centers. Additionally, Fetlar lacked a natural harbor, meaning there was no fishing industry. Since the population was originally entirely dependent on agriculture and was deprived of its livelihood through the Clearances, there were no alternative employment opportunities in fishing.

The consequence of this situation was a significant population decline in the rural areas, which had once been inhabited by hundreds of people. The impact was devastating not only on the social and economic structure of the island. Around 1800, Fetlar reached a peak population of about 860 residents, but today there are only 61 inhabitants!

Sir Arthur Nicolson, who acquired the Brough Lodge property in 1805, was also involved in these Clearances. He fenced off a significant portion of his land for sheep farming and displaced the residents from these parts of the island. During this time, he resided in the house of the former landowner, Andrew Bruce of Urie, known as the “Haa of Urie,” before eventually constructing Brough Lodge. The term “Haa” is characteristic of the Shetland Islands and refers to a grand residence or Laird’s House. The term “Haa” derives from the Old Norse word “há,” which means “of higher rank” or “of higher order.” In 1825, Sir Arthur Nicolson began building Brough Lodge.

After the death of the first Sir Arthur in 1863, the property passed to his widow, Lady Eliza Jane Nicolson, who later moved away. There is no evidence that she ever returned to Brough Lodge before her death in 1891. Eventually, a distant cousin bearing the name Sir Arthur Nicolson inherited the estate. He found that the lodge was uninhabitable, as many of the buildings had remained without roofs for the last 25 years and were generally in a state of disrepair. He conducted extensive renovation work. When he passed away in 1917, the property remained in the Nicolson family. The last resident was Lady Jean Nicolson, who lived in Brough Lodge until the 1970s. Since then, the lodge has stood practically empty and has been managed by the Brough Lodge Trust since 1998, which made tremendous efforts to preserve and restore the lodge.

THINGS TO KNOW & CURIOSITIES

Brough Lodge Chapel

Sir Arthur Nicolson is said to have had a son (also named Arthur) who died young. Locals tell a peculiar story about him. Apparently, Sir Arthur had a vision in which he saw the legendary King Arthur, who asked him what he desired most. When he replied that he wished for a son, the king promised him this on the condition that he also name the son Arthur and build a place of worship in his honor. And so, the chapel at Brough Lodge was created.

Troll Melodies

Some of the fiddle tunes from Fetlar are among the oldest and most well-known in the Shetland Islands. It is said that these melodies originated from the Trows, small trolls who live in the hills of the island. A legend revolves around Haltadans, a stone circle in the middle of the island. It tells of how the Trows wanted to dance one night and, therefore, took a local fiddler and his wife along to play music for their dances. Together, they danced a limping dance in a circle, which explains the name “Haltadans” (limping dancer). They had so much fun that they let the sunrise pass unnoticed and were transformed into stone when daybreak came, becoming the stones of the circle. The fiddler and his wife were also turned to stone in the center of this magical circle and now serve as the two central stones.

ARCHITECTURE

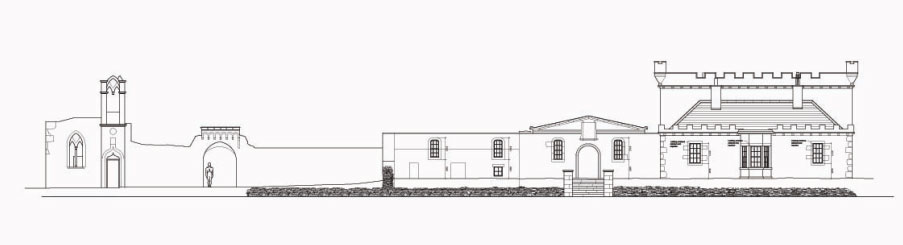

The architecture of the main house of Brough Lodge is a symphony of Georgian elegance combined with a refined blend of symmetry, proportion, and classicism. Even the building’s facade pays homage to neogothic architecture, characterized by its carefully balanced proportions and brick details. The main building consists of a two-story central block with single-story wings to the east and west, as well as a courtyard entrance to the north. The original roof was flat and surrounded on both sides by a crenellated parapet with corner turrets. In the 1950s, a modern pitched roof was installed, the battlements extended upward, and the historic corner turrets removed. In recent years, this modern alteration has been reversed at great financial expense by the Brough Lodge Fund, restoring the original roof shape.

Inside the main building, little has been altered, so most of the original fittings and structures have been preserved. Particularly noteworthy is the oval entrance hall with its curved doors that match the shape of the room, creating a majestic, almost church-like character. The windows of the lodge skillfully blend into the overall composition. They were specially designed to showcase the scenic beauty of Fetlar and create a canvas for the changing light and hues of the landscape. In 1820, the entrance was still on the south side and led into an entrance hall. By the end of the 19th century, the entrance was replaced by a window, and the entrance hall was converted into a dining room. As part of these changes, the main entrance was moved to the opposite side of the house.

The estate includes a variety of medieval buildings, a walled inner courtyard, a walled garden, and its own chapel. Undoubtedly, the historically most significant structure is the observation tower, which was once used as an astronomical observatory and housed a large telescope. This tower was built on the remains of an Iron Age broch. A broch is the term for round stone towers, of which several hundred were built during the Iron Age in the north and west of Scotland, as well as in other parts of the British Isles. They have a distinctive architectural form and are a testament to the skilled engineering of Celtic cultures. The walls of the brochs were typically constructed using dry stone masonry without the use of mortar. They were built with double walls, consisting of an inner and outer layer with an intervening cavity. This construction provided strength and stability to the structure. While these buildings also served as living quarters or for food storage and offered refuge in times of conflict, they primarily allowed for the early spotting of approaching enemies. Brochs are, therefore, significant archaeological sites that provide valuable insights into ancient construction methods and cultural practices of bygone eras.

STRUCTURAL CONDITION AT THE TIME OF ACQUISITION

After the last resident and one of the last descendants of the Nicholson family, Lady Nicolson, left Brough Lodge in the 1970s, the property remained vacant. Cold, uninhabited, and without any maintenance work, the vacancy led to deterioration in its condition. Most of the outdoor areas had decayed over the years and were partially recognizable only in the form of wall remnants.

Leakage in the roof of the main house caused severe water damage. Floor beams and interior surfaces were heavily damaged and are now in urgent need of restoration. Surprisingly, the load-bearing masonry structures remained largely intact. The overall structural integrity appeared sufficient for restoration. Therefore, measures should be taken immediately and without significant delays.

RESTORATION AND CONSERVATION MEASURES

The efforts made by the Brough Lodge Trust to save the property have already been commendable. They have restored the historic roof and the removed side turrets, as well as made significant investments in the structure.

Now, it is the task of the European Heritage Project to consolidate the existing expertise to ensure that the restoration of Brough Lodge continues with the utmost respect for its architectural heritage.

All steps and work will always follow the principle of maximum preservation of the original structure and minimal intrusion.

The first and most crucial steps in the large-scale project will be the fundamental restoration and renovation of the structures before further plans for the use of Brough Lodge can be implemented. In parallel, a roadmap for coordinating the work will be established.

FUTURE PLANS

Once the restoration is complete, the refurbished Brough Lodge is intended to be made accessible to the public. It is envisioned as an accommodation facility with an attached restaurant; details are yet to be worked out. The offerings to visitors could include an introduction to Shetland knitting, ornithological observations, or island excursions. The historic observatory could be revived, and the historical chapel could become a contemplative space for reflection.

Video post